![]()

1

ARABIC ESSENTIALS:

DRAWING YOUR ARABIC ROADMAP

Several years ago during my first few weeks of learning Arabic I found myself watching an Arab comedian one night in a London pub. Chatting to her after the show I discovered that by day she was an Arabic teacher. On hearing I was learning the language she told me, with a gleam in her eye, that the first ten years were the hardest. I’m still not sure if she was joking.

How Difficult Is Arabic?

To address the question of difficulty more technically, linguists describe Arabic as a ‘hard’ language. One system for ranking foreign languages by difficulty for English speakers uses five categories. Category 1 is the easiest, and includes languages like Spanish and French. At the other end of the scale, category 5 includes Mandarin, Japanese, and Korean. Below these, in category 4, is Arabic, alongside others such as Amharic, Burmese, Georgian, and Somali.

What Makes Arabic Hard?

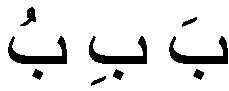

Firstly, there’s the script. At the most basic level, Arabic functions like English: there is an alphabet from which words and sentences are built. But the letters themselves take time to master. Many are distinguished from one another only by the differing placement of a dot and most are cursive, joining with those before and after. This means it takes a lot of practice to be able to distinguish between letters at speed, and to be able to read effectively. In addition, short vowels, written as small marks above or below the word, generally appear only in children’s books, poetry, and the Qur’an and other religious texts. For example, combining the letter (pronounced ‘b’), with the three vowel sounds reads, from right to left, ba, bi, bu: The absence of written vowels in most texts makes learning to read and memorizing vocabulary harder because short vowels are necessary for pronunciation and can change the meaning of a word if used incorrectly. The good news is that reading the right-to-left script, often assumed by non-Arabic speakers to be problematic, in fact comes automatically as it is dictated by the order of the letters. Try to read English from right to left: it simply doesn’t work. You are obliged to read in the correct direction.

A second source of difficulty is Arabic sounds, around a third of which do not exist in English. There are six sounds produced in various parts of the throat or back of the mouth, roughly translated as a rough kh, a deep q, a rolling gh, a h from low in the throat, the ‘ayn, which can’t really be written in English but sounds a bit like a momentary strangulation, and the glottal stop. The last of these is actually found in English, although only with non-standard pronunciation: for example, the empty ‘uh’ at the center of ‘little’ when the ‘t’ is dropped. Arabic also has deeper versions of the English t, s, z, and d, pronounced with the back of the tongue higher in the mouth. These take practice to produce accurately and to recognize reliably when listening. Students generally get there in the end, although maintaining accurate pronunciation while speaking quickly can remain a challenge even for advanced Arabists.

Arabic also boasts a formidable grammar. If you only learn colloquial Arabic you will spare yourself the more complex areas but will still need to learn and practice many core elements. While objectively not much more complex than many European languages, colloquial grammar is nonetheless different, requiring a lot of practice to feel natural. Students of standard Arabic will study more advanced grammar which, even setting aside the really advanced aspects, is expansive and incorporating it into fluid speech is a serious test. Chapter 3 has more on Arabic grammar.

The existence of multiple forms of Arabic is another major challenge. In particular, the division between standard Arabic, used for more formal situations and topics, and the various colloquial dialects used in daily life. This means that those wishing to become proficient across a range of contexts must master two versions of the language, as the structure, pronunciation, and vocabulary differ significantly between them. There is more on the standard versus colloquial issue later in this chapter.

A further source of difficulty is Arabic vocabulary. Attempts to quantify exactly how many words there are run into difficulties around what counts as a word because Arabic has a unique system whereby words are derived from the three root letters of verbs (more on root letters in chapter 3). This generates almost endless possibilities, even if many are rarely, if ever, used. In short, Arabic vocabulary is big. Very big. As my first teacher of the language warned me ominously, with Arabic, the devil is in the synonyms. Indeed, Arabic students come across new words for terms they have already learned with a frequency that well outstrips even rich languages such as English. Even well-educated native speakers regularly come across words in literary texts with which they are unfamiliar. The wide variation both between dialects and between standard and colloquial forms adds another major challenge in this regard. For many advanced students it is the size of the vocabulary that prevents them from feeling they have ever mastered the language, despite being highly proficient. This is less of an issue with a focus solely on colloquial Arabic, which uses a smaller pool of words more flexibly.

And, yes, there really are thirteen ways to make a plural. Or even more, depending how you count them. When I asked my teacher how to make a plural in my second week of studying the language and she gave me this reply, I assumed she was joking until, to my alarm, she started to write out plural forms, one after the other, on the whiteboard. Most feminine plurals are easy, in fact, usually just requiring a standard two-letter suffix to be bolted on the end of the word. The challenge is with masculine nouns, which for the most part follow one of several patterns to form a ‘broken plural.’ The word is literally broken, with additional letters inserted. Fortunately, the plural form can often be identified from the shape of the original word, meaning that over time it becomes much easier to remember, and even predict, the plurals. Despite the initial confusion they can cause, Arabic plurals should not be a cause for concern as with time they are easily managed.

Who Can Learn Arabic?

Many myths surround language learning. Some people believe they just don’t have an aptitude for it. But this is often because they didn’t succeed with languages at school, which was more likely due to a lack of motivation, enjoyment, or effective teaching than paucity of ability. Conversely, there is a view that some are naturally gifted and, dropped into any foreign land, will soon be conversing having effortlessly absorbed the language.

Yet I have met no one who has reached a high level of Arabic without a great deal of study. It’s true that a minority of people seem to memorize words more reliably just having heard them, while others enjoy foreign languages or have an interest in a particular country, which motivates their learning. But anyone can learn a foreign language, including Arabic, and while some will take longer than others, this probably has more to do with motivation, quality of teaching, and having a clear study plan than with any innate linguistic ability.

If you are already familiar with the Arabic letters and corresponding sounds you have a head start. This is the case with many Muslims who do not speak Arabic but who have studied the Qur’an, learning to read and recite without necessarily knowing the meaning. You will still have to start at the beginning but initial familiarity with the script will help you move faster through the initial stages. In a full-time study program, this is likely to accelerate your progression through the earlier stages by a month or two.

Experience of learning other languages helps with learning Arabic but is certainly not essential. It helps already to understand the components of a language, which may come from a knowledge of English grammar or from learning foreign languages. If you know how verbs, nouns, adjectives, participles, prepositions, and objects function in a sentence you will have a reference point for Arabic structure and grammar. But if these terms are unfamiliar you can learn them as part of your Arabic studies, preferably assisted by a good teacher. For those with a knowledge of Latin, those hours spent learning grammatical cases will pay dividends during the later stages of Arabic grammar as the concept will already be familiar.

Modern Standard Arabic versus Colloquial Arabic

Avoid Arabic No-Man’s-Land

The breadth of the Arabic language, together with the standard–colloquial dichotomy, means that it is vital to consider at the start of your studies the form you want to prioritize, what your end goal is, and whether you have the time and resources to get there. Without a plan you may set off in the wrong direction and find after months, or years, of study that you have a developed a knowledge of areas of Arabic that don’t serve the purpose you require. Or you may find yourself in the linguistic no-man’s-land in which very many Arabic students find themselves, at the end of the study period with intermediate-level standard Arabic and some basic colloquial: the product of a great deal of work, and far beyond the basics of ‘holiday Arabic,’ but insufficient for professional or significant social use. This chapter helps you through this planning process by explaining the different types of Arabic, what they are used for, and how long progress is likely to take.

Modern Standard and Colloquial Arabic: What’s the Difference and Which Should I Learn?

Modern Standard Arabic (otherwise known as MSA, standard Arabic, or fusha, in Arabic) is “proper,” or formal, Arabic. It derives from classical Arabic, which is found in the Qur’an. Standard Arabic is largely consistent across the Arabic-speaking world and Arabs value highly the ability to speak it well. It is used in news reporting, speeches, interactions in formal settings, and almost all written material. The vocabulary is extensive, and the grammar complex and exact. It is cumbersome and unwieldy for everyday, informal settings, however, and using it in such a context sounds inappropriately formal to a native speaker’s ear.

Colloquial Arabic (‘ammiya in Arabic) refers to the various local dialects found across the Arabic-speaking world. In broad terms, Arabic-speaking countries of the Levant region (Jordan, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon) share a dialect, with some variations, which is generally understood elsewhere. Iraqi, Gulf, and Egyptian Arabic are three further main dialects, the latter of which is widely understood thanks to the popularity of Egyptian films. The dialect spoken in other north African countries (Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria) forms another significant grouping, again with variations, which is very distinct and not easily understood by Arabs elsewhere.

Colloquial Arabic has less grammar than standard Arabic, a reduced vocabulary, and easier verb conjugations. Perhaps less elegant but more practical, it is used among friends, family, and colleagues in all kinds of informal daily exchanges. Most colloquial vocabulary derives from standard Arabic, and much of it bears a resemblance, but each dialect has its own lexicon, particularly when it comes to everyday terminology. Together with strongly varying pronunciation this makes each dialect unique. Colloquial Arabic is rich in idioms, sayings, and colorful expressions but lacks terminology for more sophisticated areas such as politics, economics, and the law. Consequently, when discussing such topics speakers are obliged to adopt the vocabulary, if not necessarily the more formal sentence structures, of standard Arabic. For native speakers and the few non-Arabs that reach an equivalent level, colloquial Arabic is sometimes used in formal settings as a linguistic tool. Political speeches, for instance, are typically in standard Arabic to convey gravitas and authority, but the speaker may switch to more colloquial language when he or she wishes to connect with the audience on a more personal or emotional level.

To give an example of how an everyday sentence can vary depending on the register, to ask, “Would you (plural) like to sit inside because of the cold weather?” in standard Arabic, you would say:

Transliterated: hal tureeduna an tajlisu fi ad-daakhil li-anna at-taqs baarid? This sounds very formal and rather long-winded for such a simple question.

A slightly less formal version of this might read:

Transliterated: b-tahibbu tajlisu fi ad-daakhil li-anna at-taqs baarid? Note that this is largely the same as the standard Arabic version above, but with the very formal first few words substituted for something more conversational. To convey the difference between these in English, the more formal of the two approx...