![]()

INTRODUCTION:

A NEW HISTORY OF WELWYN GARDEN CITY

The State of the Art

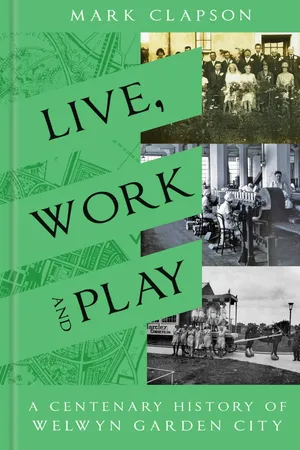

This book was commissioned by the Welwyn Garden City Heritage Trust to mark the centenary celebrations of one of the most influential English towns in the world. Although countless words have been written about the origins, development and significance of WGC, a new history is long overdue. Beyond the symbolic significance of the anniversary itself, WGC deserves a fresh historical appraisal. In this book, its social, cultural and economic history is intertwined with an account of its planning, origins and expansion since 1920.

Until recently, histories of WGC have fallen into three broad fields. The first might be termed the ‘the insider histories’ written by followers of the ‘founding father’ of the Garden City Movement Sir Ebenezer Howard. Frederic James Osborn (FJO), Richard Reiss and Charles Benjamin (C.B.) Purdom are notable here. Howard had provided the rationale and key planning principles of garden cities in his Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1898), later published as Tomorrow: A Peaceful to Real Reform (1902). The book was essentially a template for the garden city he initiated at Letchworth in Hertfordshire in 1903. And in 1919 Howard was proactive in getting Welwyn Garden City, the second garden city, off the ground. The town centre shopping mall, the Howard Centre, and the thoroughfare Howard’s Gate, are both named after him.

A second and arguably more objective field comprises the town planning histories of WGC, undertaken largely by academic historians of town planning, and some scholars of urban development. While only a couple of academic planning history books exclusively examine the history of WGC itself, it features prominently in a number of scholarly works on the garden cities of the twentieth century. The significance of WGC in town planning history is evidenced, furthermore, in its place in many general academic histories of British town planning, and in evaluations of the international impact of the Garden City Movement during the twentieth century.

And the third pool of WGC histories might happily be summarised as ‘local history and heritage’. Many enthusiastic local historians, activists in heritage organisations, and oral and visual historians have been keen to document and promote the social history of WGC, particularly from the point of view of those who have lived there.

This book aims to embrace all three approaches, to provide a well-researched and scholarly account of the social and planning history of WGC, drawing upon a wide range of sources: official reports; academic histories, local histories; oral histories; newspapers and journals. It is hoped that the book will be of interest not only to an academic but also to a popular readership, which will hopefully include many citizens of the Garden City itself, whether they are long-established residents or more recent migrants.

The ‘Insider Histories’

Most people living in Welwyn Garden City have heard of Frederic Osborn, or ‘FJO’ as he called himself and as he was often referred to by his contemporaries. He has both a school and a major road near the railway station named after him. As we will see, he was a major player in the development of WGC, serving as Secretary to Welwyn Garden City Ltd for many years. On the national and international stages, he was also a key mover in professional town planning organisations, an adviser to British political parties and governments, and possibly the most influential exponent of the Garden City Movement during the twentieth century. Osborn moved from Letchworth to Welwyn Garden City soon after WGC was designated in 1919. He lived at Guessens Road, in the opulent heart of town, just down the street from Howard, who died in 1928. During his long lifetime, most of it spent in WGC, Osborn wrote a number of histories of the town. His Genesis of Welwyn Garden City (1970) covers the earlier days of the garden city and Welwyn Garden City Ltd, to its transition to a new town after the Second World War, and its near-completion as a planned entity by 1970. And in his co-written book New Towns: Their Origins and Achievements (1970) Osborn assessed the national and overseas impact and legacy of the Garden City Movement, and gave a summary history of WGC. As both activist in and chronicler of the British Garden City Movement at home and abroad, Osborn always placed his experiences at WGC at the centre of his work. His transatlantic correspondence with his friend Lewis Mumford also provides much information on how FJO evaluated life and the built environment in WGC, and interpreted social and economic change between the 1930s and the ’70s.

In the Woodhall area of WGC a couple of culs-de-sac are named after other leaders in the development of WGC. One is Chambers Grove, named after Sir Theodore Chambers, who became Chairman of Welwyn Garden City Ltd in 1920. Chambers also has a footpath named after him – Sir Theodore’s Way – in the shopping area, and a monument to him in Parkway. There is another little street in Woodhall called Purdom Road, named after C.B. Purdom. It is a modest little street compared with Osborn Way, a spatial expression of the pecking order in the movers and shakers that made Welwyn Garden City. As we will see, Osborn and Purdom were allies for many years, both followers of Howard and enthusiasts for the WGC that they were building. Purdom was an advocate of planned new ‘satellite cities’ to be designed along the Garden City model, writing a book on this, The Building of Satellite Towns, during the 1920s. He viewed WGC as a key exemplar of both. But as early as 1928, just eight years after the beginnings of the town, Purdom was out of favour with many of his elite colleagues. He would later write a somewhat jaundiced autobiography, Life over Again (1951), which also acts as a partial history of WGC. Purdom updated his analysis of WGC as a satellite town during the wartime debates on the future of housing and town planning in Britain. Following the destruction and losses to property caused by the Blitz and other air raids, WGC would play a major role in the emergent new towns programme following the New Towns Act of 1946, becoming a new town itself in 1948.

The memoir to Captain Richard L. Reiss, written by his wife Celia, also provides invaluable information about life in Welwyn Garden City. A politician, housing reformer, humanitarian and a leading member of Welwyn Garden City Ltd, Reiss played an important role not only in managing the growth of the Garden City, but in his patronage of sports and leisure clubs. He also spread the word about WGC to the wider world. Osborn, Purdom and Reiss figure prominently in this book.

Town Planning Histories of Welwyn Garden City

The most recent, readable and thorough history of WGC is to be found in Stephen V. Ward’s The Peaceful Path: The Hertfordshire New Towns (2016). His book takes its title from Howard’s Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. WGC is viewed as at least as important as its predecessor, Letchworth, and the significance of the actions and writings of Frederic Osborn are given their due weight. In addition to his work on WGC, Osborn was a leading national campaigner for garden cities, and during the Second World War, as head of the Town and Country Planning Association, he fought tirelessly for both a new towns programme, and a more systematic national town planning apparatus. Osborn could, and did, claim some credit for the formation of the Ministry of Town and Country Planning in 1943, and the New Towns Act of 1946.

Osborn personifies the link between the Garden City Movement and the new towns. WGC has been viewed both by Ward and by this writer as the metaphorical umbilical link between the British garden cities of the first half of the twentieth century, and the new towns programme after the Second World War. Unlike Letchworth, WGC was redesignated as a new town in 1948, gaining a second phase of planned growth. This history is also examined in Frank Schaffer, The New Town Story (1972), a book that almost but not quite qualifies as an insider history. Schaffer was a founder member of the Ministry of Town and Country Planning, established in 1943, and from 1965 became the Secretary for the Commission for the New Towns. The Commission took over the management of WGC from the Development Corporation in 1966. Schaffer was also a leading light in the Town and Country Planning Association, and known to Osborn. As an advocate of the post-war new towns programme, Schaffer pointed to the achievement of the new towns in providing a new and more prosperous life for millions of people, and he defended them, including WGC, from unfair criticisms that they were more ‘soulless’ or prone to social problems than older urban cities and towns.

One of the leading planning historians was Gordon E. Cherry, whose studies of British town planning during the twentieth century have contributed much to our understanding of Howard, Letchworth and WGC as influencers on the nature and trajectory of new community planning. However, Cherry’s The Evolution of British Town Planning (1974) and Town Planning in Britain Since 1945 (1996) suffer from a sometimes simplistic account of the rise of British town planning, and of the influence of Howard and his followers within it. Dennis Hardy’s Garden Cities to New Towns (1992) underplays the importance of WGC in the history of British new communities of the twentieth century.

Back during the 1970s, when the Open University (OU) was beginning to make a splash in distance learning across Britain, it provided a popular second level unit entitled ‘Urban Development’. In The Garden City (1975) Stephen Bayley critically discussed the origins of planned new towns and garden cities, from the factory villages of the nineteenth century to the larger new towns of the last century. WGC was given a great deal of attention, not least because of the role of its influential architect Louis de Soissons, who was appointed Chief Architect by WGCL in April 1920. His synthesis of modern town planning with a Georgian-influenced architectural style was also much praised by Ray Thomas and Peter Cresswell, The New Town Idea (1975). It is pause for thought that these course units are among the most detailed and thought-provoking histories of WGC from garden city to new town. In establishing the national and international reputation of the OU in the new city Milton Keynes, the academics were drawing upon the histories of WGC and Letchworth and earlier planned new towns.

The importance of WGC is also explored in studies of the British Garden City Movement. The work of Anthony Alexander, Robert Beevers, Michael Hebbert and Standish Meacham, to take just four examples, has delved into the history of WGC from many different angles, demonstrating that there is not one agreed interpretation of the history and significance of the town. Alexander for example, in Britain’s New Towns: Garden Cities to Sustainable Communities (2009), argues that the history of WGC from garden city to new town and now towards a more sustainable urban environment fulfils some key aspects of Howard’s original intentions while demonstrating the town’s adaptability to change. By contrast, in Garden City Utopia: A Critical Biography of Ebenezer Howard (1988), Robert Beevers shows how the original, perhaps naïve, idealism of Howard’s thought was undermined by the actual process of building garden cities, and the constraints and political realities faced by their exponents. WGC is an obvious case in point. In Regaining Paradise: Englishness and the Early Garden City Movement (1999), Standish Meacham also analyses a process of dilution of Howard’s ideals, arguing they relied on romantic notions of past living that would find a difficult fit into the twentieth century. In a number of scholarly contributions to books on the Garden City Movement, for example, ‘The British Garden City: Metamorphosis’ (1992), Michael Hebbert also demonstrates some key mismatches between the original template of Howard and developments in Letchworth, WGC and other experiments in garden cities during the twentieth century.

Local and Heritage Histories of Welwyn Garden City

Among the most useful books to anyone, academic or otherwise, interested in WGC is Maurice de Soissons’ Welwyn Garden City: A Town Designed for Healthy Living (1988). Maurice was the son of Louis, yet his history of WGC, whilst properly noting its achievements and successes, also draws attention to some of the problems in the town’s history, from internal divisions in Welwyn Garden City Ltd, to local opposition to both the garden city and the new town, tensions between local political organisations, social problems between the wars and since, and also difficulties in meeting demand with the supply of materials and services. It is a skilful book, moreover, blending a corporate and planning history of WGC with its social, economic and political development. The current book has been quite dependent upon it.

The work of the Welwyn Garden City Heritage Trust (WGCHT), funded by successful applications to the Heritage Lottery Fund, makes the most significant contribution to Live, Work and Play. The Trust was begun in 2005 when a few people, who later became trustees, took up arms successfully against a planning application in the garden city. There followed a realisation that the town lacked a dedicated champion for its heritage and so the Trust was established as a charity and not-for-profit company in December 2006. Since then it has created an invaluable collection of oral testimonies and other materials. Of particular value to this book has been the collection of oral history interviews with Welwyn Garden City residents for Where Do You Think We Worked? and Where Do You Think We Played? Two publications carry the same titles and draw upon those interviews. Another series of interviews was Where Do You Think You Lived?, although these remain unpublished at the time of writing. Oral history can be problematic, as people tend to remember selectively, and often reinterpret the past in a positive light. This is known as ‘retrospective contamination’ by oral historians. But oral history also supplies lively memories and personal experiences of life and work in twentieth-century WGC that are often absent from the printed record.

The DVD Welwyn Garden City: A Brave Vision (1996) was the idea of the WGC Society, who obtained sponsorship and practical help from Rank Xerox to create the original film. It was issued to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the town in 1995. The initial format was a cassette with copyright held by Hertfordshire County Council (HCC) but by 2006 this format had been largely replaced by the DVD and sales had dried up. Recognising the quality of the production, the Trust approached HCC with a view to acquiring the copyright and converting the format to a DVD, which HCC were happy to accept. The film was relaunched to celebrate the town’s ninetieth anniversary, since when over 500 copies have been sold throughout the UK and overseas. The ability of the Trust to gain funding for the promotion of local history is a testament both to those who have worked for it, and also to the ‘can-do’ culture that had been instilled in WGC since its earliest days. The WGCHT web address is www.welwyngarden-heritage.org. The website contains many quotes from interviews, pictures and photographs, many relevant to this present book.

Another example of an active and concerned citizenry is the aforementioned Welwyn Garden City Society, much of whose work is available online at http://welwynhatfield.co.uk/wgc_society. The Society is dedicated to preserving the character and qualities of the built environment and the amenities of the town. In addition to publicising WGC, conserving its buildings, and promoting an engaged and well-informed civic culture, the Society is now at the forefront in defending the Garden City from a new phase of planned development and infill that threatens the very essence of the Garden City principles that have served WGC so well over the past 100 years.

![]()

2

DREAMERS AND DOERS: THE MAKING OF WELWYN GARDEN CITY

Industrialisation, Urbanisation and the Search for Solutions

The County of Hertfordshire in south-east England is the home, some might say the cradle, of the world’s earliest modern garden cities. Letchworth was the first, designated in 1903, but its successor, Welwyn Garden City, is just as well known in the county, the country and across the world as its slightly older sibling.

The story of Ebenezer Howard and his founding of Letchworth and Welwyn Garden Cities has been told extensively, but historical context is required in order to understand the antecedents of WGC, and the ideas and working examples that influenced Howard. The two Hertfordshire garden cities were the latest chapters in the story of planned industrial villages and model communities, a story stretching back to the Industrial Revolution that began during the later eighteenth century, and which continued to evolve throughout the nineteenth century.1 These were the factory villages built for the working population, and some innovative garden suburb experiments. They were a fascinating part of the wider story of humanitarian interventions and progressive reforms to improve the social, cultural and economic conditions of the unplanned industrial towns and cities, particularly the poorest, overcrowded and insanitary districts.

Factory Villages in Britain During the Industrial Revolution

Among the most famous British examples are the company housing experiments built by paternalistic employers for textile workers during the Industrial Revolutio...