![]()

1

Introduction

Not all that long ago in geological time, giant marsupials roamed the forests, plains and swamps of Australia. All are now extinct. One group, the diprotodontids, were particularly huge, much larger than any modern marsupial. Nototherium was the size of a cow, and Diprotodon and Zygomaturus, that of a rhinoceros. The latter had a massive metre-long skull. There were, also, giant kangaroos, Macropus (the forerunner of modern kangaroos), Sthenurus, and Procoptodon, which stood about 3 m tall! Preying upon these grazers and browsers was another giant, Thylacoleo carnifex, the marsupial lion.1

About 100 000 years ago, these great creatures began to die out. The reasons are unknown. Giant mammals of all kinds in all continents died out similarly. Gross changes in world climate are usually invoked as the cause. Some of the giant marsupials survived until ~30 000 years ago, e.g. the kangaroos, Macropus ferragus and Sthenurus. Since Aborigines arrived at least 40 000 years ago, it has been suggested that they hunted them to extinction, or else, through their use of fire to flush game or provide easy traverse, grossly changed ancestral habitats (Jones 1968; Merrilees 1968). Thus, it is argued, forests were razed, vast grasslands formed and the forest dwellers of the time were denied their livelihood.2

Today, in drier times, the survivors of those marsupial giants are the modern kangaroos. Five species, the euros (Osphranter) and giant kangaroos have come down to about one-third to one-quarter the size of their ancestors, but the sixth, the red kangaroo (Megaleia3) (Plate 1), is unchanged. It appeared in the late Pleistocene (over 12 000 years ago), after the others, and is perhaps the most modern form of kangaroo. All kangaroos and wallabies are, however, closely related to one another. In captivity, some will even interbreed, though the hybrids are all sterile (Calaby & Poole 1971).

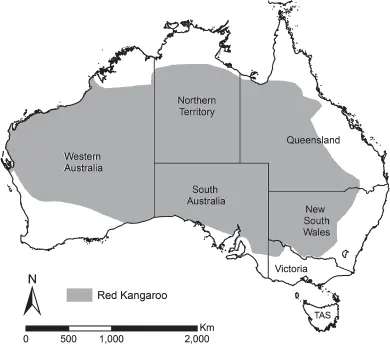

In any part of Australia today, one species of kangaroo or another can be found, adapted to wet temperate forests, arid plains or the monsoonal tropics. Only one species is truly restricted to the arid inland, the red kangaroo (Fig. 1.1). That so large an animal should thrive in so capricious an environment is remarkable because it is dependent on green grass for food, even in drought.

Australia is a droughty land. The great size of the arid hinterland makes it one of the driest continents on Earth. Flat, waterless, lightly timbered plains commence abruptly inside the eastern highlands and stretch almost unrelieved for ~3000 km to the western coast, encompassing ~5 000 000 km2 in all. The whole of Europe could be neatly packaged inside it. This is the range of the red kangaroo.

Figure 1.1: Distribution of the red kangaroo in Australia.

For almost 100 years after the First Fleet landed in Australia in 1788, the environment of Central Australia defied exploration by the European colonists. The experiences of white explorers are proof of the harshness and aridity of the environment. Captain Charles Sturt,4 a British explorer, was forced back by the terrible heat and desolation of Sturt’s Stony Desert. Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills,5 through folly and hard luck, perished on Cooper’s Creek, a little further inland. The impetuous Ludwig Leichhardt,6 a Prussian explorer and naturalist, disappeared without trace to this day, probably in the Simpson Desert or even further inland.7 Ernst Giles,8 that hardy romantic, lost his horses and his offsider Alfred Gibson off to the west in the desert Giles named after him, to survive himself, only by superhuman endeavour. He walked back across the desert ~150 km to base camp in stupefying heat, driven almost mad by thirst and hunger. Only John McDouall Stuart9 triumphed. This doughty Scot, much praised by Sturt for thoroughness as a surveyor on the expedition mentioned above, crossed Australia from south to north right through the driest parts, and did not lose a man. He succeeded by finding water, establishing camp there, and then setting off to find more. If he found it, the expedition moved on. If he failed to do so, he retreated to the base camp to replenish his water bags and take another course. In this way he slowly picked his way across the land. Twice he was turned back to Adelaide by hardships. There he remained a scant few months to regroup and rest, and then was off again. Stuart succeeded in his third attempt. We now know that through his thoroughness, determination and bushmanship, Stuart found the only possible corridor through that forbidding country – a great feat, but the ordeal cost him his health.

It comes as a surprise, then, to learn that this hot, dry and desolate land, explored by European men at such cost, was inhabited by thriving Aboriginal tribes. Indeed, throughout Central Australia, McDouall Stuart traversed a densely populated region inhabited by the largest and most powerful tribe of inland Australia, the Aranda people. To them, it was not a desolate land. About them were familiar plants and animals, astonishing really for so arid a region. The fauna in these areas, for example, ranges from earthworms, snails, fish and frogs, to hardy reptiles, birds and mammals. Many creatures survive by clinging to the only permanent moisture, the few rock holes in the ranges and rivers. Others burrow or are strictly nocturnal to avoid the heat. A few are drought hardy.

But how can such large animals like the red kangaroo survive there? Indeed, how did the Aboriginal peoples do so?

The key to the success of the Aboriginals was behavioural. They knew their country so well, its waterholes both temporary and permanent and places to find food, that life, sometimes a rich one, was possible. They conquered the land with their wits. As mentioned previously, however, the red kangaroo had one special ecological requirement – green grass to eat. Of all things in an arid land this can be rare stuff.

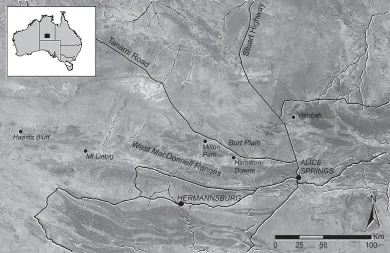

The red kangaroo lives mainly where there are lightly timbered and grassy plains; it is rare in the true open deserts. Of all Australian marsupials, it is the one whose ecology is best understood.10 Though the red kangaroo has been studied at eight widespread localities throughout its range, this book concentrates largely on Central Australia (Fig. 1.2). There are several reasons for this. Above all, it is the country that I know best. Luckily, also, my five-year study there extended through good seasons and bad. The simple environment, and sharp climatic shifts, induced clear-cut changes in the kangaroos’ lifestyle.

Figure 1.2: The region of focus in this book. Labels are provided for key townships, study locations and landscape features.

But there is one other great advantage. European settlement in Central Australia was closer to its origins and to the primordial environment in the Centre than elsewhere in inland Australia. Some of the grazing pioneers are still alive, and provided accounts of red kangaroos (and other fauna) in the early days. Several of them arrived to mine gold at Arltunga or Tanami, others to graze sheep and cattle. Some, not all that long ago, had described their experiences to chroniclers about the penetration of white man to their tribal lands. And some, born before that penetration, had not long since died. As a boy, old ‘Sloper’, a Warramunga, saw his tribesmen turn McDouall Stuart back at Attack Creek on 25 June 1860. He died at Tennant Creek in 1956 about 103 years old. The recollections of these European graziers and Aboriginal tribesmen helped answer such questions as these: were kangaroos abundant then or not; what was the environment like, especially the vegetation, before white man released domestic stock upon the land? After all, there were still Aboriginals who clung to their tribal lives and beliefs; so much could be learnt from them during my time in Central Australia.

When I first went to Central Australia in 1957, red kangaroos were abundant. Mobs of 50 and 100 were commonly seen on the open plains. Larger mobs were rare. The largest, seen just 15 km south of Alice Springs, was ~1500 strong.11 As I approached, it seemed that the entire plain got up and moved away.

In the late 1950s, kangaroos were a hot political topic. They were regarded as pests depriving cattle and sheep of food. They were accused of eating out the pastures or fouling those they did not, so that stock would not eat them. According to news reports, red kangaroos were highly abundant, occurring ‘in millions’ throughout the Northern Territory, even in the ‘Top End’, as the country above Newcastle Waters is called.

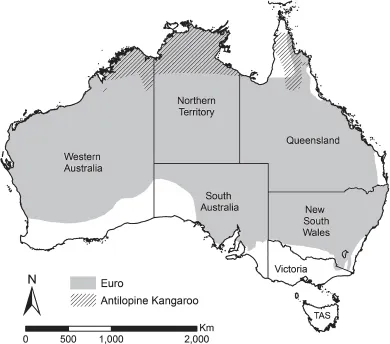

Collecting trips throughout the Northern Territory soon showed that the kangaroo referred to in the Top End was not the red kangaroo but the antilopine kangaroo (Osphranter antilopinus) (Fig. 1.3). This kangaroo has slender lines and similar colouring to the red kangaroo, as well as its habit of living on the flat country, so the mistake was readily understandable. Grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) were also incorrectly reported. In the Centre, what had been reported as grey kangaroos were in fact female red kangaroos, the ‘blue fliers’, whose fur is often smoky grey. Grey kangaroos do not live in the Centre; they live along the east and south coasts of Australia, ranging inland to the edge of semi-arid country.

Figure 1.3: Distribution of the euro and antilopine kangaroo in Australia.

So the red kangaroo’s characteristic of being strictly a dry country animal was upheld. Indeed, it is one of only two kangaroos found in the truly arid country. The other is the euro (Osphranter robustus) that lives in the hills and ranges of inland Australia. Its distribution extends to the mountains of the Great Dividing Range in the east where it is blackish in colour, and is called the wallaroo (Fig. 1.3).

There is little risk of confusing the two kangaroos of Central Australia. The euro sticks to the mountain ranges and valleys, has a long hairy coat of a brownish colour and is stockily built with a sturdy powerful gait. The red kangaroo lives on the surrounding plains, has a slender build, a short soft fur, and an easy graceful gait. Any doubt can be resolved by the characteristic white and black patches on either side of the muzzle of red kangaroos.

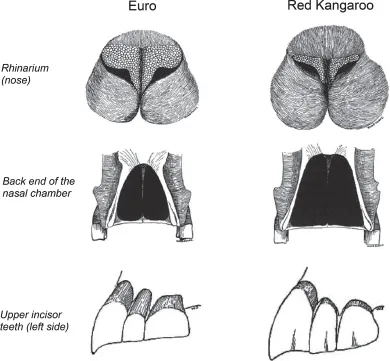

There are other distinguishing features on the head. The naked nose of the euro is larger and more dog-like than that of the red kangaroo, the cheek bone (zygoma) is much broader in the euro and the foramen magnum (the hole at the base of the skull where the spinal cord emerges) is distinctly smaller. Other differences can be seen by comparing the nasal chamber and the upper incisors (teeth) (Fig. 1.4).

Thus, the issue of incorrect identification and distribution of the red kangaroo was simply solved. But there still remained the problem of pastoral fouling and grazing by red kangaroos, and there still existed a plethora of biological questions to answer. For example, why were red kangaroos so abundant on open plains and creeks during droughts, and more so on some than others? Where did they disappear to after rain? Why were they so rare in the deserts at all times? Why did they sometimes congregate to form large mobs? What did they eat and did they compete severely or at all with cattle and sheep? How did kangaroos foul pastures as claimed? Did the movement of large mobs indicate migrations? How could five to 10 kangaroo shooters work one 500 km2 plain 50 km north of Alice Springs night after night in the 1950s without making an impression on numbers? Their breeding would seem to be prodigious for such to happen. So what were the reproductive processes, and what ensured reproductive success?

Figure 1.4: Examples of differences in the anatomy of red kangaroo and euro. Adapted from Wood Jones (1924).

There were further unanswered questions. Why did kangaroos appear to be more numerous on cattle country than land never stocked? Was it due to the stock waters man had made? If so, why were kangaroos so rarely seen at water? Had kangaroos always been so numerous? If so, why was there no mention of them in McDouall Stuart’s journals? Why had he to shoot a horse to stave off death from starvation in October 1862 near Mt Hay, in the heart of red kangaroo country, when a shot aimed blindly across the plains at night a century later could not have failed to fell one?

Intensive studies of the kangaroo’s biology and ecology began to answer these questions in the late 1950s. Life-history studies began on captive animals in Adelaide (...