![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Aboriginal legacy of the Burke and Wills Expedition: an introduction

Ian D. Clark and Fred Cahir

The Aboriginal story of the Burke and Wills Expedition and relief expeditions is at once multi-faceted and complex with many interconnected threads that have rarely been teased out in historical analyses. In many respects the Aboriginal story has been overshadowed by the tragedy and misfortune of the expedition in which seven men, including Burke and Wills, died. Yet the exclusion of Aboriginal perspectives is a structural matter, as epitomised in Moorehead’s analysis. The description of central Australia as a ‘ghastly blank’ (Moorehead 1963, p. 1) where the land was ‘absolutely untouched and unknown, and except for the blacks, the most retarded people on earth, there was no sign of any previous civilization whatever’, is representative of the exclusion of Aboriginal people from the narrative and if Aboriginal people are discussed, it is often in racist tones. As Allen (2011, p. 245) rightly pointed out:

To a certain extent, the Aborigines were classified by the Europeans as part of nature rather than culture, as being located within a landscape which itself was conceived as being empty and primordial, where European exploration brought the land into existence and formed a starting point for Australian history. However, the explorers were passing through lands that had resident Aboriginal populations, territories that were already mapped and named. In considering the interior of Australia empty, the explorers were unaware of the fact that the land, its waterholes, animals and plants, were charged with cultural and mythological meaning, and that unseen boundaries were constantly being crossed.

The Aboriginal story is concerned with the bushcraft of expedition members and their flawed use of Aboriginal ecological knowledge; it is the story of the Aboriginal guide Dick who ensured that trooper Lyons and McPherson did not perish at Torowoto; it is the Yandruwandha adoption of John King and the colonial response in thanking these people with gifts that included breastplates and the establishment of a reserve for Moravian missionary activity on the Cooper; it is the contribution of various members of the original expedition and relief parties to knowledge of Aboriginal societies and the development of anthropology; and it is Yandruwandha and other Aboriginal oral histories of the expedition including one that concerned the death of Burke (see Figure 1.1). The authors of the chapters in this book have found that the historical records concerning the Burke and Wills Expedition and subsequent relief expeditions are capable of yielding a considerable quarry of material from which Indigenous perspectives can be gleaned. It follows that the barriers that have for so long kept Indigenous perspectives out of the Burke and Wills story were based not on lack of material but rather on perception and choice. A literary curtain has been drawn across Burke and Wills historiography since the early 20th century – Indigenous perspectives have been seen as peripheral to the central task of the historical writings. With this publication we are pleased to contribute to a re-emergence – Indigenous Australians who had been ‘out’ of the Burke and Wills story for over a century are now returning to centre stage. It needs to be acknowledged that while much of this ‘new’ evidence is derived from non-Indigenous exploration records, it has also been possible to uncover Aboriginal perspectives in those records that complement Aboriginal oral histories.

In the 1960s Australian historians were criticised for being the ‘high priests’ of a cult of forgetfulness, for neglecting Aboriginal history and for excluding a whole quadrant of the landscape from their research. The same criticisms may be levelled at much of the recent historical study of the Burke and Wills Expedition, despite the richness of the Aboriginal side of this story. Yet this was not always the case. During the expedition’s jubilee years (1861–1911), Indigenous peoples occupied an important place in historical accounts of the Expedition. In the title of this book we emphasise this point through the use of the subtitle ‘forgotten narratives’. Aboriginal people and Aboriginal themes were more prominent in early writings compared with later 20th-century histories. This is particularly evident in the flourish of publications around the centenary years (Fitzpatrick 1963; Hogg 1961; McLaren 1960, Moorehead 1963; Southall 1961), which are remarkable for the fact that although they are keen to discuss what went wrong with the expedition, they are relatively silent on Aboriginal people. The basic truths about exploration that were evident to contemporary commentators such as William Lockhart Morton, Marcus Clarke, George Rusden and Henry Turner had been left out of the studies that emerged at the time of the centenary celebrations. Taking Ian McLaren’s (1960, pp. 235–236) analysis as representative of this excision, we can see that he neglects to include Aboriginal themes in his summary of the tragedies and mistakes that caused the death of seven expedition members. While recent studies have begun to consider the contribution of some of the scientific members of the expedition and subsequent relief expeditions to the broader field of Aboriginal studies (Tipping 1979; Taylor 1983; Bonyhady 1991; Beckler 1993; Allen 2011), there has not yet been any systematic attempt to construct an Aboriginal history of the expeditions.

Jan Fullerton, the Director-General of the National Library of Australia in 2002, considered the Burke and Wills transcontinental expedition to be ‘one of Australia’s great stories. The deaths of seven members of the exploration party, despite the expedition achieving its goal of reaching the Gulf of Carpentaria, have been transformed in the past 150 years into a national myth of heroic endeavour’ (Bonyhady 2002, p. iii). Tim Bonyhady (2002, pp. 6–7) argued that, apart from the bushranger Ned Kelly, no other colonial figures have loomed as large in Australian culture: ‘While successive generations have focussed on very different aspects of the expedition and assessed it very differently, they have never lost interest in it. The very complexity of the expedition, always the stuff of conflicting accounts, has made it ripe for interpretation and reinterpretation’. Marcus Clarke (1877, pp. 201f) took the view that the expedition was part of:

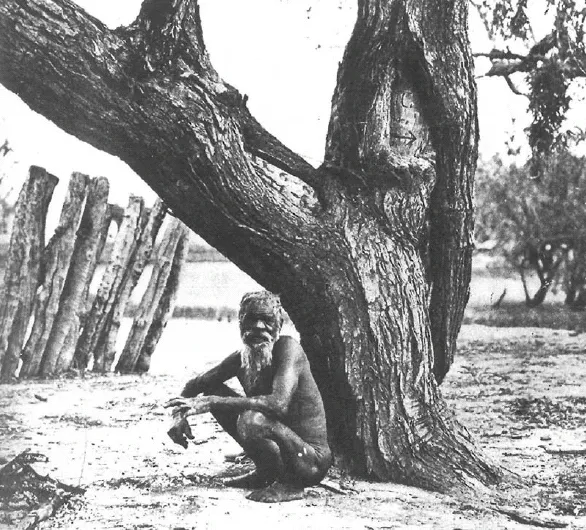

Figure 1.1: ‘Memento of the Burke and Wills Expedition: William Brahe’s tree, Cooper’s Creek, 1911’. Sydney Mail, 11 October 1911, p. 33. National Library of Australia.

According to Bonyhady (1991, p. 275) this is a ‘photograph originally published in the Sydney Mail in 1911, showing the site of the depot camp on Cooper’s Creek with the tree marked by the explorers, an Aboriginal man said to have been “a young tribesman at the time of the expedition”, and the remains of the stockade built by Brahe and his companions’. Aaron Paterson (pers. comm. 15 September 2012) noted that this Yandruwandha man was known as ‘Baltie’ and that he spoke a dialect of Yandruwandha known as Parlpa.madra.madra (‘stony tongue’ or ‘heavy tongue’). He died at Karmona Station, which was once part of Nappamerrie Station.

… a most glorious era in history of Australian discovery. Within two years of the death of the leaders from starvation on Cooper’s Creek, tierces of beef were displayed in an intercolonial exhibition at Melbourne, salted down from cattle pasturing on the spot where they perished! Settlement has followed their track right across the continent … But it is sad to think that a few forgotten fishhooks would have preserved their lives. It is lamentable to read of the blunders of some, the gross neglect of others, and of the series of appalling disasters which followed from inexperience, incapacity, and rashness.

Ernest Favenc (1908, p. 186) considered the Burke and Wills expedition was ‘of greater notoriety than that of any similar enterprise in the annals of Australia’. Ernest Scott (1928, p. 231) noted that the Burke and Wills story is one of the most famous of Australian inland exploratory enterprises, and that the ‘éclat with which it started and the tragedy of its ending have invested it with an atmosphere of romance’.

Roy Bridges (1934, p. 367) argued that they ‘won undying fame not less by tragedy than by achievement’. The Historical Subcommittee of the Centenary Celebrations Council (1934, p. 214), in its historical survey of Victoria’s first century, noted that although ‘the continent was crossed by a remnant of the party, dissensions, faulty leadership and organisation, want of tact, foresight, and judgement, ignorance of bushcraft and pitiful blundering, joined to a series of fatalities resulting from divided forces and faulty communication and contact, made it a tragedy in which seven lives were lost’. Colwell (1985, p. 9) commented that while Burke succeeded in crossing the continent, he ‘discovered that the limitless arid regions, the natural home of Aboriginal food gatherers and hunters, denied life to white men unable to capitalise on the shifting pockets of wild life and fickle water holes’.

Early histories of the expedition include Andrew Jackson’s (1862) historical account, Puttmann (1862), Foster (1863), Grad (1864), Pyke (1907), Watson (1911), Birtles (1935), Dow (1937) and Frank Clune’s (1937) Dig: A Drama of Central Australia. The centenary of the expedition in 1961 produced a number of historical revisions including Oakley’s (1959) short story ‘O’Hara 1861’, McLaren’s (1960) essay, Garry Hogg’s (1961) With Burke and Wills across Australia, McKellar’s (1961) Tree by the Creek, Ivan Southall’s (1961) Journey into Mystery, Alan Moorehead’s (1963) Cooper’s Creek and Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s (1963) lecture ‘The Burke and Wills Expedition’. Writing about the Aboriginal people of the Torowoto district, Southall (1961, p. 40) explained to his readers that they ‘were very primitive, but they knew how to kill. They were brave and skilful hunters and they no more trusted the white man than the white man trusted them’.

Several authors have published accounts of their attempts to retrace the tracks of Burke and Wills, in particular Thallon (1966), Judge and Scherschel (1979) and Bergin (1981). Bergin’s retracing is of interest as he enlisted the services of two Aboriginal guides to accompany him on his journey, Nugget Gnalkenga, a Pitjantjatjara chilbi (elder) and an experienced cameleer, and Frankie Gnalkenga, his Arunda son. Recent histories include Bonyhady (1991) and Murgatroyd (2009). Bonyhady’s (2002) catalogue was published to accompany an exhibition staged at the National Library of Australia. There have also been studies of particular members of the expedition, such as Ludwig Becker (Blanchen 1978; Tipping 1978a,b, 1979, 1991; Heckenberg 2006; Edmond 2009), Hermann Beckler (Voigt 1991; Beckler 1993), King (McKellar 1944; Attwood 2003; Turnbull 2011) and Wills (McLaren 1962; Van der Kiste 2011). Joyce and McCann (2011) edited a volume exploring the scientific legacy of the expedition.

Many of the early histories of Victoria and Australia were concerned with the tragedy and misfortune of the expedition which saw the death of seven members, including Burke and Wills. Many sought explanations for the demise of Burke and Wills and put the blame on poor choices, human failings or simply ‘bad luck’. With the exception of Henry Turner (1904) and George Rusden (1897), who considered the decision not to take Aboriginal guides and the expedition’s inexperience in dealing with Aboriginal people were critical factors in its demise, most early commentators focused on other issues. Some critics argued that Burke and Wills should have been able to survive at Cooper Creek: ‘where untutored Aborigines were able to pick up a living’ with their spears and stone tomahawks, a ‘white man should not starve with his rifle and iron one’ (Bonyhady 1991, p. 218).

Rusden thought that Burke lacked the kindly fatherly control needed to win the affection of the native race, and lamented that the expedition was ‘unaccompanied by an Australian native whose skill as a hunter would have spared the carried food for emergencies’ (Rusden 1897, vol. 3, p. 112). Turner (1904, vol. 2, p. 105) took the view that Burke, as leader, ‘proved to be deficient in the necessary qualifications of tact and patience’ and that he ‘knew nothing of bush-craft or surveying, and was without any experience in dealing with the aborigines’. Although Aboriginal guides were usefully employed at various stages between the Darling and the Bulloo rivers they were not taken on to Cooper Creek. Between the Bulloo River and Cooper Creek, expeditioners sought to avoid contact with Aboriginal groups they met along the way and reached for their guns when Aboriginal people attempted to interact with them. On their journey to the Gulf of Carpentaria and back to Cooper Creek, Burke and Wills came to appreciate the value of Aboriginal tracks and wells, but they continued to resist Aboriginal attempts at communication. Reynolds (1990, p. 11) noted that Burke and Wills learnt the value of following Aboriginal tracks when returning from Carpentaria; floundering in a bog they came upon a hard, well-trodden path which led them out of the swamp and on to drinking water and yam grounds. Just after leaving the Cooper Creek depot ‘A large tribe of blacks came pestering us to go to their camp and have a dance, which we declined. They were very troublesome, and nothing but the threat to shoot them will keep them away … from the little we have seen of them, they appear to be mean-spirited and contemptible in every respect’ (Wills 1863, pp. 179–180). According to Brahe, who had been left in charge of the depot at Cooper Creek, the instructions from Burke, concerning the Aborigines, were that if any annoyed the depot they were to be shot at once.

Henry Reynolds (1990, p. 33) believed that a fundamental shortcoming of the expedition was its failure to profit from Aboriginal expertise; he considered this surprising given the widespread private use of Aboriginal guides in all parts of the continent from the earliest years of settlement. In the last few weeks of their lives, when Burke and Wills attempted to live like the Aborigines, they learnt too late one of the basic truths of Australian exploration. John Greenway (1972, p. 142) called the Burke and Wills tragedy ‘an impossible truth’. Colwell (1985, p. 71) mused that when Burke, Wills, Gray and King were en route to the gulf they were ‘never far from inquisitive human eyes’.

What the Central Australian Aboriginals thought of the lumbering evil-smelling camels and their strange white attendants will never be known. Their territory and possibly sacred ground was being inv...