Ecological Engineering for Pest Management

Advances in Habitat Manipulation for Arthropods

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Ecological Engineering for Pest Management

Advances in Habitat Manipulation for Arthropods

About this book

Ecological engineering is about manipulating farm habitats, making them less favourable for pests and more attractive to beneficial insects. Though they have received far less research attention and funding, ecological approaches may be safer and more sustainable than their controversial cousin, genetic engineering. This book brings together contributions from international workers leading the fast moving field of habitat manipulation, reviewing the field and paving the way towards the development and application of new pest management approaches.

Chapters explore the frontiers of ecological engineering methods including molecular approaches, high tech marking and remote sensing. They also review the theoretical aspects of this field and how ecological engineering may interact with genetic engineering. The technologies presented offer opportunities to reduce crop losses to insects while reducing the use of pesticides and providing potentially valuable habitat for wildlife conservation.

With contributions from the USA, UK, Germany, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, Kenya and Israel, this book provides comprehensive coverage of international progress towards sustainable pest management.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Ecological engineering, habitat manipulation and pest management

Introduction: paradigms and terminology

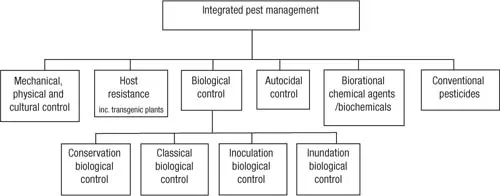

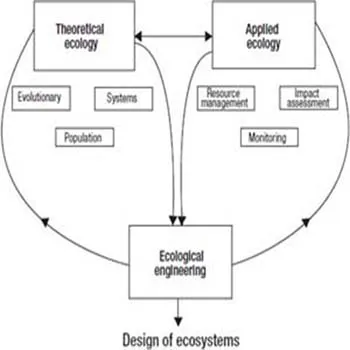

© Kluwer Academic Publishers. Originally published in Eilenberg, J., Haejek, A. and Lomer, C. (2001). Suggestions for unifying the terminology in biological control. BioControl 46: 387– 400, Figure 1. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.

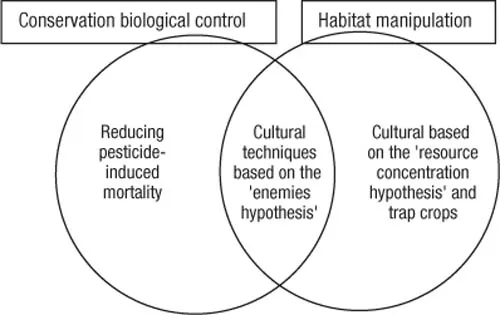

© Kluwer Academic Publishers. Adapted from and originally published in Gurr, G.M., Wratten, S.D. and Barbosa, P. (2000). Success in conservation biological control. In Biological Control: Measures of Success (G.M. Gurr and S.D. Wratten, eds), p.107, Figure 1. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ecological engineering

| Application | Examples |

| Ecosystems used to reduce or solve a pollution problem | Wastewater recycling in wetlands, sludge recycling |

| Ecosystems imitated to reduce or solve a problem | Integrated fishponds |

| Recovery of an ecosystem after disturbance is supported | Mine restoration |

| Existing ecosystems modified in an ecologically-sound manner to reduce an environmental problem | Enhancement of natural pest mortality |

Adapted from and reproduced with permission from Mitsch, W.J. and Jør...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Chapter 1: Ecological engineering, habitat manipulation and pest management

- Chapter 2: Genetic engineering and ecological engineering: a clash of paradigms or scope for synergy?

- Chapter 3: Agroecological bases of ecological engineering for pest management

- Chapter 4: Landscape context of arthropod biological control

- Chapter 5: Use of behavioural and life-history studies to understand the effects of habitat manipulation

- Chapter 6: Molecular techniques and habitat manipulation approaches for parasitoid conservation in annual cropping systems

- Chapter 7: Marking and tracking techniques for insect predators and parasitoids in ecological engineering

- Chapter 8: Precision agriculture approaches in support of ecological engineering for pest management

- Chapter 9: Effects of agroforestry systems on the ecology and management of insect pest populations

- Chapter 10: The ‘push’pull’ strategy for stemborer management: a case study in exploiting biodiversity and chemical ecology

- Chapter 11: Use of sown wildflower strips to enhance natural enemies of agricultural pests

- Chapter 12: Habitat manipulation for insect pest management in cotton cropping systems

- Chapter 13: Pest management and wildlife conservation: compatible goals for ecological engineering?

- Chapter 14: Ecological engineering for enhanced pest management: towards a rigorous science

- Index