![]()

1

Reimagining fire management in fire-prone northern Australia*

Jeremy Russell-Smith Peter J Whitehead

Summary

The northern savannas, occupying a quarter of the Australian land mass, constitute the most fire-prone landscapes of a fiery land – in recent years, on average, 18% of the savannas have been burnt each year. Land use is predominantly given over to extensive beef cattle pastoralism – although over much of the rangelands this is at best an economically marginal activity, especially in frequently burnt, higher rainfall northern regions. Outside of urban centres most of the savanna human population is Indigenous, increasingly rapidly, and remains impoverished. Much of the northern cadastre is Indigenously owned outright, or is subject to continued rights of access and use under Native Title arrangements. In this paper we articulate a distinctly northern Australian understanding of and approach to the management of fire, matched to the biophysical and social realities of the north. Despite many obstacles to effective management associated with remoteness, sparse population and limited transport and other infrastructure, management of fire can be improved for positive ecological and social outcomes over a large part of the Australian land mass. Taking advantage of emerging carbon and biodiversity environmental services developments, skilled fire management offers a culturally apt enterprise opportunity where few others exist.

Introduction

Australia is rightly recognised as a fire-prone continent. Fuelled by public media and official enquiries (e.g. Ellis et al. 2004; Teague et al. 2010), the dominant popular perception is that fire is a particularly southern Australian phenomenon, characterised by life- and property-threatening conflagrations under extreme summer fire-weather conditions. Indeed, under envisaged climate change scenarios of marked increase in number of days of extreme temperature and diminishing regional water availability (CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology 2007; Garnaut 2008; Indian Ocean Climate Initiative 2012), wildfire activity in densely populated south-eastern and south-western Australia is likely to increase in decades to come. Given contemporary patterns of human settlement, it is entirely reasonable therefore that such preoccupation with southern landscape fire management issues will continue.

However, a broader understanding of the geographic scale and frequency of fire patterning in Australia reveals that fire incidence in the ‘deep south’ is, in fact, scant by comparison with periodic fire occurrence under typically low rainfall conditions in central Australia, and especially compared with annual–biennial fire recurrence under monsoonal conditions in north Australian savannas (Russell-Smith et al. 2007; Murphy et al. 2013). Contrary to the narrow views of Australia’s only ostensibly ‘national’ bushfire enquiry (Ellis et al. 2004), such fire regimes in ‘regional Australia’ are exerting significant impacts on a range of regional cultural, production, and biodiversity values (e.g. Dyer et al. 2001; Allan and Southgate 2002; Williams et al. 2002; Russell-Smith et al. 2003; Woinarski et al. 2007a). The greenhouse gas and particulate emissions resulting from these fire regimes, and the radiative forcing, associated especially with savanna fires, have global-scale climate implications (e.g. Luhar et al. 2008; Meyer et al. 2008; ANGA 2011).

In response to this generic national myopia concerning landscape fire issues in northern Australia, here we set out to (1) describe contemporary fire patterning across the savannas, (2) explore the particular biophysical and societal features associated with and giving rise to those patterns, and especially (3) make the case that savanna fire, rather than being seen simply as an aberrant, problematic landscape property, in fact can afford savanna land managers – and especially disadvantaged Indigenous communities – significant employment opportunities and cultural benefits in a re-imagined, diversified savanna economy.

Fire mapping and contemporary burning patterns

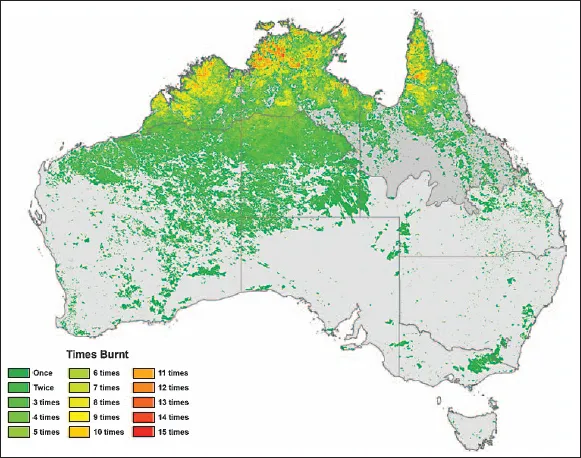

Remotely sensed data sources and website portals have started to transform widely held misperceptions that bushfire events, and their social, environmental and economic implications, are a particularly southern Australian phenomenon. On the basis of continental mapping of large fire-affected areas (>~2–4 km2) for the period 1997–2004 derived from AVHRR imagery, Russell-Smith et al. (2007) observed that 76% of total mean fire-affected area (508 000 km2 p.a.) occurred in the northern savannas. Expressed as a proportion of continental land area defined by rainfall classes, a mean of 0.6% of southern Australia (53% of continental land area) was fire-affected each year, 5% of central Australia (25% of continent), and 23% of northern Australia (22% of continent). These general patterns are reflected also in updated, 1997–2011, continental mapping of the frequency of large fires derived from AVHRR imagery (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Frequency of large fire-affected areas (>~2–4 km2) derived from AVHRR imagery, 1997–2011. North of line indicates tropical savannas region as defined by the Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre. (Data from: Western Australia Department of Land Information – Landgate).

At a continental scale, fire extent is substantially explained by rainfall seasonality, i.e. the relative amount of rainfall received in the wettest compared with the driest quarter (Russell-Smith et al. 2007; Murphy et al. 2013). In the monsoonal north, intense bursts of high summer rainfall separated by an extended annual dry season (southern winter and spring) ‘drought’, during which next to no rain may fall for 6 months or more, drive an annual cycle of elevated fire risk alternating with periods of little or no fire risk. In the arid centre, erratically variable periods of above average rainfall and subsequent high rates of plant growth may alternate with dry periods extending over several years to decades. Susceptibility of landscapes to fire therefore changes over longer than annual cycles, but very large wildfires occur with some regularity, fuelled mostly by grassy fuels like spinifex (Triodia spp.). In parts of mesic southern Australia (especially forested regions), vulnerabilities increase with fuel accumulation over many years, so that when the mostly summer fires occur they can be extraordinarily intense.

For the tropical savannas, mean annual rainfall declines rapidly from >2000 mm in parts of the far north to ~500 mm in southern regions. The annual mean extent of large fires follows this general trend (Chapter 2). Significantly, modelling of fire extent with a range of biophysical variables (e.g. antecedent rainfall, or fire, in previous year(s); land use) suggests that rainfall is sufficiently annually reliable in the north to support annually recurrent burning (Russell-Smith et al. 2007; Chapter 2). With declining, less annually reliable rainfall, fire propagation relies on cumulative antecedent rainfall for the development of adequate fuel loads and fuel continuity (Allan and Southgate 2002).

A salient feature of contemporary savanna fire regimes concerns the predominance of fires occurring in the latter part of the dry season, typically under severe fire weather conditions (periodically strong south-easterly winds, high temperatures, low humidities, fully cured fuels). For example, of the annual mean 338 000 km2 of the tropical savannas region affected by large fires over the period 1997–2011, 69% occurred in the late dry season months August–November. Fire regimes dominated by frequent, large, late dry season fires are commonplace in many regions of northern Australia, especially the Kimberley region in the north-west, the Top End of the Northern Territory, and western Cape York Peninsula (Fig. 1.1). Contemporary north Australian fire regimes have significant impacts on regional biodiversity values (e.g. Russell-Smith and Bowman 1992; Woinarski et al. 2001, 2010, 2011; Franklin et al. 2005; Russell-Smith et al. 2010, 2012), and have significant implications for greenhouse gas emission estimates and related carbon dynamics (Cook and Meyer 2009; Murphy et al. 2009, 2010; Russell-Smith et al. 2009a; Meyer et al. 2012).

Of particular relevance here, ‘Prescribed burning of savannas’ is listed as an accountable activity under the provisions of the Kyoto Protocol. While the protocol was only ratified by Australia relatively recently, Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory (NGGI) has reported on savanna burning emissions from 1990. Typically, accountable greenhouse gas emissions contribute between 1–3% of Australia’s NGGI (ANGA 2011). However, following international convention, Australia’s NGGI considers only emissions of the accountable greenhouse gases methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Carbon dioxide itself is not accounted for since it is assumed (often incorrectly, see Cook et al. 2005; Cook and Meyer 2009) that CO2 emissions in one burning season are negated by vegetation growth in subsequent growing seasons (IPCC 1997). In fact CO2, together with more reactive species (e.g. the ozone precursors comprising CO, volatile organic compounds and oxides of nitrogen) that are released into the atmosphere over a typically long burning season, is likely to have a substantial impact on regional atmospheric composition and its inter-annual variability.

In the past few years very substantial developments have taken place in the north, providing opportunities for land managers to undertake strategic landscape-scale fire management to deliver commercial greenhouse gas emission offset projects, particularly under the mantle of the Commonwealth Government’s Carbon Farming Initiative (CFI; Commonwealth of Australia 2013). Leading the way has been the Western Arnhem Land Fire Abatement (WALFA) project, operating over 28 000 km2 of Aboriginal-owned land under a 17-year voluntary (sensu Bayon et al. 2006) offset arrangement with a multinational energy corporate (Russell-Smith et al. 2009b; Heckbert et al. 2011, 2012; Cook et al. 2012). In its first 7 years of operation WALFA has successfully reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 37.7% (or 127 000 t CO2-e yr−1) relative to the 10-year pre-project baseline period (Russell-Smith et al. 2013). In 2013, the first savanna burning project was declared under CFI law on Fish River Station, a 1700 km2 property managed on behalf of Aboriginal landowners by the Indigenous Land Corporation (see www.ilc.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u = 335) and is now eligible to trade in Australia’s compliance market. At the present time, many more projects across the north are already, or in the process of being, CFI-registered. While the present federal government’s proposals will, if brought into law, alter the way credits are bought and sold, key features of the CFI will be retained, including eligibility of savanna fire projects.

Achieving significant greenhouse gas emissions abatement, and more effective savanna landscape fire management generally, are thus components of the same fundamental problem – how do we practically and economically reduce the incidence and extent of contemporary late dry season wildfires?

Ecological and cultural landscapes

We approach this question by first considering why it has proved so difficult to manage Australia’s savanna landscapes to avert unwelcome environmental and social change, despite the absence of intense population pressures.

Ecology

North Australian savanna environments are relatively intact structurally and many areas are recognised for their important biodiversity values, including major centres of endemism (with many plants and animals that occur nowhere else; Woinarski et al. 2007a). But there have been losses of ecological function – chiefly evidenced in biodiversity declines – at several levels and across large areas (Woinarski et al. 2001, 2011; Franklin et al. 2005). Scattered richer patches of the landscape are asked to maintain natural production but at the same time support economic (agricultural and pastoral) production. More resilient and reliably productive environments (like wetlands) are valued highly by many different interests or sectors (Jonauskas 1996). Rivers are mostly unregulated. Most rivers carrying high wet season flows cease flowing during parts of the annual dry season, so that many water-dependent ecosystems are maintained by springs or other near-surface groundwater. Primary industries (agriculture and mining) rely heavily on groundwater extraction, even in the high rainfall areas, and so can impact these systems.

Temperatures are uniformly high, and often very high. Rainfall is intensely seasonal with no equivalent to the more equable wet tropics of the east coast of Australia. In the seasonal tropics, timing of the onset and cessation of wet conditions is highly unpredictable, and evaporation rates greatly exceed precipitation for most of the year. Hence the length of the growing season is variable but often short. Extreme weather events are common (storm, cyclone) and recur on a range of spatial and temporal scales. Landscapes are old, frequently reworked, and highly weathered. Soils are often of low fertility or low water-holding capacity and in many settings highly erodible, and so limiting for agriculture (Woinarski and Dawson 2002). These features have contributed to the problematic history, including repeated failures, of agriculture in northern Australia (Cook 2009).

Many areas of northern Australia contain exploitable concentrations of minerals and fossil energy, some of which are already in production and many others are under development. Mineral extraction often involves relatively low-grade deposits requiring movement of large quantities of overlying or intervening rock, which build long-term problems of acid formation during the subsequent oxidation of waste rock and drainage from it (e.g. Harries 1997). On-site processing can add to pressures on water availability and also compromise water quality. The Northern Territory Government has recently acknowledged weaknesses...