![]()

1

HOW PLANTS GROW

Cambium – the uniting force

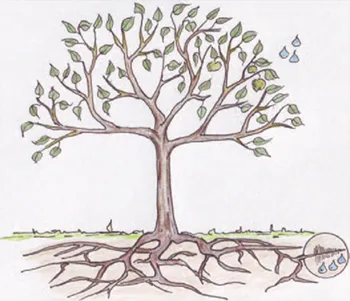

Scratch a woody twig and you will find a bright green layer called the cambium. The two plant parts, roots and shoots, growing in different directions, are united by a complex ‘plumbing’ network. This is known as the cambium layer. This layer links the microscopic root hairs gathering soil nutrients and water, with the shoots and leaves manufacturing food (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The xylem carries water and moves in one direction – straight up from the roots – and exits as water vapour through the leaves. The contents of the phloem move osmotically in both directions, carrying nutrients from the roots combined with simple sugars manufactured in the leaves. Together they penetrate and sustain all living parts of the plant.

These two elements combine and are spread through the plant from the veins in every leaf to the tip of every root.

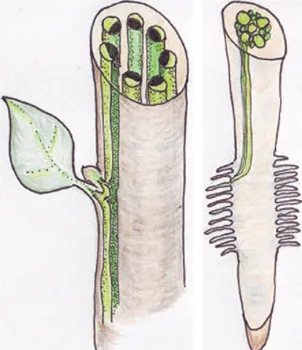

The cambium layer consists of vascular bundles made up of two distinct types of ‘plumbing’ or vessels (see Figure 1.2).

The xylem and phloem form the core of the root. The xylem takes up the water and the phloem takes up minerals from the soil via root hairs. The phloem also distributes sugars manufactured in the leaves to where it is needed in the plant. Together they penetrate and sustain all living parts of the plant. The xylem (pronounced ‘zi-lem’) is in charge of conducting water from the roots to the tip of the uppermost leaves – one-way traffic heading straight up and exiting through the leaves as water vapour. This water vapour is why it is often cooler in the shade of a broad-leaved deciduous tree on a warm day. The phloem (pronounced ‘flowem’) carries sugars manufactured in the leaves to the whole of the plant, depending on where the plant needs nourishment. Well-nourished plants with well-nourished buds produce more flowers and fruit than impoverished buds.

Figure 1.2 The cambium layer is made up of vascular bundles of xylem (dark green) and phloem (light green). The cambium layer, carrying nutrients up from the roots (right), and combining these with sugars manufactured by the leaves (left).

How the riches of the cambium layer are disbursed determines how well parts of the plant are nourished. This distribution of nourishment, and therefore growth, is determined by plant hormones that are active in growth points otherwise known as meristems (pronounced ‘merry stems’).

Hormones and meristems (points of growth)

As we all know, hormones are powerful things. Anyone that has lived with teenagers knows as much. They govern both the growth and development in all living things, including plants. A group of hormones called auxins govern which buds get nourished and produce growth, and which don’t. Points of growth like buds are sites of active cell division stimulated with auxins (plant hormones) and are called meristems. Meristems will develop into buds producing leaves and wood, or flowers and fruit. Every seed/seedling starts with two meristems – the radicle and the plumule that give rise to all other growth points (see Figure 1.3).

As the plant grows, branching occurs. These branches/stems emerge from the growth points, meristems that develop after the germination stage. Their growth is governed by the concentrations of the plant hormones auxin and cytokinin.

These hormones are manufactured in the meristems (growth points) where plant cells are rapidly dividing to produce growth. They are found in the root tips and in buds.

Figure 1.3 This seven-day-old snow pea started with two meristems. The radicle forms the roots, and the plumule that forms the above-ground parts. Note the roots are branching and the seedling mix is clinging to the microscopic root hairs that draw up water and nutrients. The plumule is just unfolding its seed leaves that hide a meristem that gives rise to the rest of the future pea plant.

Buds – apical and otherwise

Buds form the above-ground growth points on plants. They contain the actively dividing cells and plant hormones that produce growth. Due to the balance of auxins, however, not all buds were created equal.

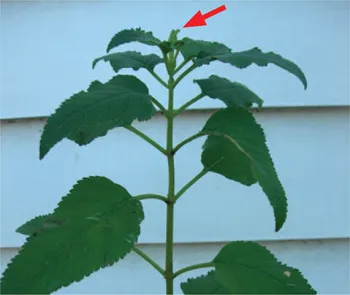

Apical buds

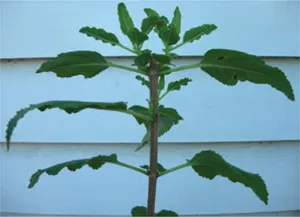

These buds are those at the very top (apex) of the plant or plant stem and produce auxins that keep this top bud extending towards the maximum amount of light available. Auxins also inhibit the growth of side or axillary buds. The apical bud, fuelled with hormones, gets the priority grab of water, nutrients and sugars required for growth. This means that it can grow taller, bask in the light and out-compete the rest by suppressing those buds below it, creating what is referred to as apical dominance. Wherever there is a stem with an active apical bud going straight up, it will continue to do so regardless of the buds below it. There are plenty of people out there who are like this, and needless to say, they (the apical buds) should be trained to make sure that the whole plant can realise its maximum plant potential (see Figure 1.4).

The apical bud is essential for creating a strong central leader (trunk) in trees or other woody plants; however, it needs to be discouraged to form bushy plants. Successful lavenders would never have a central trunk, as their talent lies in forming a rounded shape in order to carry more flowers. Lavenders are a shrub, so are naturally inclined to be bushy. Pinching out the apical bud will ensure that the bush will branch from the base. This is often done in the nursery as soon as the cutting has struck. Groundcovers are plants that naturally grow horizontally. However, the density of the branchlets and subsequent leaves will be increased if the apical buds (on the end of the main stems) are pinched out. This will make the plant much more effective as a groundcover.

Figure 1.4 The most active growth is at the apex of the plant governed by the apical bud that pushes onwards and upwards. This is essential for a central trunk in trees.

Axillary buds

To create bushy plants the solution is easy; just pinch out the top, apical bud, and there will be an immediate reallocation of plant resources to promote axillary or lateral (side) buds (see Figure 1.5).

Axillary buds, active or inactive, are found on the sides of the stems at the leaf nodes. They originate from meristems located between the base of leaves and the stem. They are the poor and completely oppressed, until stimulated into growth by a change in hormone levels brought about by removing the apical (top) bud. These axillary buds will one day form the side branches of the plant.

Figure 1.5 When the apical bud is removed, the meristems that have been suppressed in the leaf axils now become active. This is essential to encourage a bushy plant.

WHY PRUNE?

- Pruning can direct how water and nutrients are distributed through the plant

- It maximises the potential of certain growth points/meristems

- By understanding how the cambium and hormones work, the pruner can direct growth to where it is needed

- The apical bud will always dominate the rest of the plant, creating vegetative growth heading upwards

- Axillary buds growing sideways produce more flowering/fruiting wood

It stands to reason that the more light and nutrients a bud/node/leaf receives, the more active and productive it will be. The resulting healthier, stronger buds are more likely to produce flowers and/or fruit rather than the vegetative growth produced by the apical bud.

As branches grow more horizontally or sideways (lateral growth), the flow of the cambium (xylem and phloem) slows, rather than racing to the top of the plant. As the flow of the cambium slows, each bud/node has a greater opportunity to reap its riches. Thus the plant will produce more flowers and fruit on lateral growth than on vertical vegetative growth.

Not only are the hormone levels changed when the apical bud is removed, the axillary buds/nodes now have more access to light. This means they are more likely to develop leaves and stems which then photosynthesise, thus increasing the plant’s food-manufacturing opportunities.

How plants make their own food

Photosynthesis is the process where the green parts of the leaf (chloroplasts) interact with light energy from the sun, carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and water via the xylem to create simple sugars. There is no life on Earth that does not depend on this process.

The chemical equation is:

6CO2 +6H2O + light energy = C6H12O6 + 6O2

which means:

Six carbon dioxide molecules plus six water molecules plus light energy creates one molecule of sugar and six molecules of oxygen.

This simple sugar, combined with nutrients and water from the soil or growing media, supplies all the materials to make the plant and all other life on Earth.

The exposure of leaves to light is imperative. Look at the inside of a dense shrub; there are no leaves (see Figure 1.6).

Note the small bumps on the stem of the box plant in Figure 1.6. These are old meristematic sites (from leaves or small stems) that have gone into dormancy due to lack of light. Cutting back to these growth points and allowing light in can reactivate the meristems creating new growth.

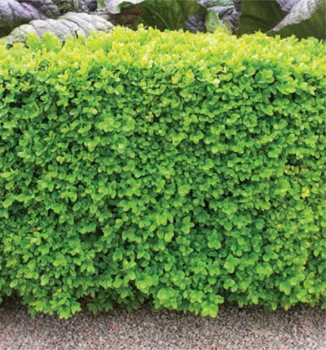

Only the external parts of the shrub that receive light produce leaves (see Figure 1.7).

Photosynthetic surfaces may not always be what we think they are. It is the green pigments found in chloroplasts that perform photosynthesis. Chloroplasts are found not only in leaves, but in green stems and unripe fruit. These plant parts must be exposed to light to photosynthesise and therefore manufacture simple sugars.

Figure 1.6 The inside of this dense Buxus gets hardly any light, therefore it cannot support leaves.

Figure 1.7 The outside of the bush is well clothed with leaves due to their exposure to the light.

Leaves and other plant parts

What, you may ask, does a grey or even black leaf do? How do cacti work, or ‘air’ plants with no roots at all? One thing is certain, tear any leaf or stem and you will find some ‘green’ inside. These are the green pigments in the chloroplasts that manufacture food by photosynthesis. Cacti have made their stems into photosynthetic surfaces, while the ‘leaves’ are the spines. Air plants, such as Spanish moss that hangs from trees in the Deep South of the USA, get their water from the humid atmosphere and their grey furry leaf coating limits moisture loss. The variety of plant physiology and adaptation to climate is mind-blowing; however, all plants have in common the ability to pho...