![]()

1

FRAMEWORK: ASSESSING WATER IN SLOPE STABILITY

Geoff Beale, Michael Price and John Waterhouse

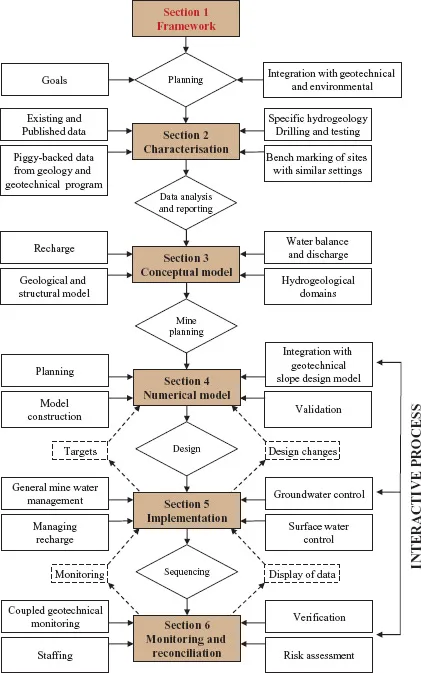

This section of the book outlines the framework used to assess the effect of water in slope stability. It describes the fundamental parameters used in the assessment (Section 1.1), the key elements that make up the hydrogeological model (Section 1.2), and general water management in open pit mines (Section 1.3), each of which is considered in the Hydrogeological and Geotechnical Modelling phases of the slope design process (Figure 1.1).

1.1 Fundamental parameters

1.1.1 Porosity and storage properties

1.1.1.1 Porosity and drainable porosity

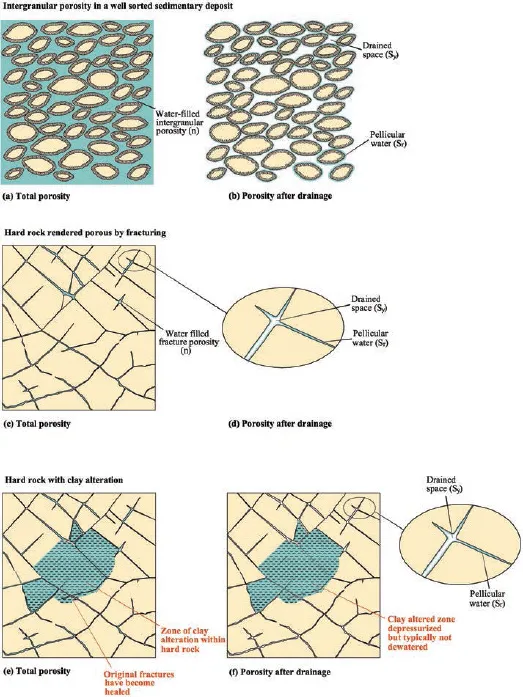

The porosity of a rock mass (n) is defined as the fraction of the total volume of that rock mass that is occupied by void space. It is usually expressed as a percentage (though in calculations it must be expressed as a fraction). For saturated rock, the void space is occupied by water (Figure 1.2a). For unsaturated rock, the void space is occupied by a mixture of water and air (Figure 1.2b). Interconnected porosity is the fraction of the total volume of rock occupied by interconnected void space. The interconnected porosity can be subdivided into drainable porosity (or specific yield) and non-drainable porosity (or specific retention).

The sequences in Figure 1.2 illustrate that, for any given saturated rock mass, only part of the interconnected void space will drain under gravity. This space, expressed as a fraction or percentage of the bulk volume of the rock, is termed the drainable porosity or specific yield (Sy). Even after a long period of drainage time, some water will remain within the interconnected pore spaces due to surface tension, adhering as films to mineral grains and fracture surfaces, and sometimes completely filling the finer pores or fractures; this is termed pellicular water (Figure 1.2b). There will also be some pores that cannot drain because they are not interconnected; it is therefore useful to distinguish between total porosity (which may include isolated, unconnected voids) and interconnected porosity, through which fluid movement is possible. Many igneous and metamorphic rocks, for example, will contain some primary porosity around or within crystals, but these voids are rarely interconnected to a significant extent and so this porosity is seldom significant for water storage. A sample of Ailsa Craig microgranite was found to possess a primary porosity of 0.9 per cent but this was mostly within the altered feldspar microphenocrysts (Odling et al., 2007); it could not therefore contribute to either specific yield or to permeability, which were extremely low (Section 1.1.2).

Generally in this book the term porosity, without a qualifier, can be assumed to refer to interconnected porosity. The void space that does not drain under gravity is termed the non-drainable porosity. The fraction or percentage of retained water to the bulk volume of rock is termed the specific retention (Sr). The sum of the specific yield (Sy) and the specific retention (Sr) equals the interconnected porosity (n). The use of the once-popular term effective porosity is discouraged (Lohman et al., 1972) because it has been used to mean different properties by different people.

In terms of gaining a practical understanding of porosity and pore pressure, most materials that are encountered within and around mine sites can be classified into three groups, as follows.

- Unconsolidated or semi-consolidated materials that exhibit porous-medium conditions.

- Hard rock materials that exhibit fracture flow conditions.

- Dual-porosity materials that exhibit a combination of porous-medium and fracture flow conditions.

1.1.1.2 Porous-medium conditions

Porous-medium conditions usually occur within most unconsolidated or poorly consolidated strata, such as sands, silts, clays, evaporite deposits and some poorly-consolidated clastic rock types. Within these rock and soil types, virtually all of the groundwater is contained within the primary interstitial pore spaces of the formation itself (Figure 1.2a).

Figure 1.1: The hydrogeological pathway in the slope design process

The porosity of these materials is mostly controlled by the interstitial spaces between grains, which typically range from about 10 per cent to about 30 per cent of the total volume of the formation (n = 0.1–0.3), but may be more than 50 per cent (n = 0.5) in some poorly-consolidated fine-grained materials. A cubic metre of the rock mass may therefore typically contain 100 to 300 litres of groundwater. Clay materials may have a very high total porosity, in some cases in excess of 50 per cent (n > 0.5). However, for many clays and other fine-grained sediments, the drainable porosity typically represents only a small proportion of the total porosity, in many cases less than five per cent of the total volume (Sy < 0.05) and in some cases less than one per cent (Sy < 0.01).

The porosity is typically higher in well-sorted materials where the grain size of the formation falls within a relatively narrow band. The drainable porosity will also be higher in well-sorted materials provided that the grain size is relatively large (e.g. sands and sandstones). Some well-sorted materials (e.g. chalks and some silts) may have very uniform grain sizes but the grains and hence the pores and pore connections are so small that very little water will drain from them under gravity. The total and drainable porosity tend to decrease in poorly sorted materials where the void spaces between the coarser grains can be filled with finer particles. The total and drainable porosity also tend to decrease in materials where the void spaces have become filled with secondary chemical deposits (cements).

Figure 1.2: Porosity, drainable porosity (specific yield) and specific retention. (a) and (b) Intergranular porosity in a well-sorted sand before (a) and after (b) drainage. (c) and (d) Fracture porosity in a hard rock before (c) and after (d) drainage. (e) and (f) Hard rock with fracture porosity and clay alteration before (e) and after (f) drainage.

1.1.1.3 Fracture flow conditions

Fracture flow conditions usually occur within most competent (consolidated) rock types, such as igneous, metamorphic, cemented clastic and carbonate rocks, and in consolidated coal formations. Although the unfractured rock may contain some pore space, this is mostly unconnected and much of the groundwater within these rocks occurs within fractures in the rock mass (Figure 1.2c). Groundwater movement in these materials therefore occurs mostly by fracture flow and drainage from the unfractured blocks will be effectively non-existent.

The interconnected porosity of competent (consolidated) rock types is dependent on the frequency of open fractures and joints, and may typically range from less than 0.1 per cent to about three per cent of the total volume of the formation (n ≤0.001–0.03). A cubic metre of the fractured rock mass may therefore contain from less than 1 to around 30 litres of groundwater. As with intergranular pore spaces, of the total groundwater contained within the fractures, only a portion of this will drain out if the rock pore pressures are reduced by passive drainage or pumping (Figure 1.2d).

Both the total and drainable porosity are typically higher in settings where the rock mass is well fractured and jointed, and the joints are open. Porosity may also be significantly higher where the rock mass itself contains intergranular porosity or other forms of secondary porosity such as vugs or solution voids. The total and drainable porosity tend to decrease where fractures or voids have become filled during the mineralisation process or by secondary chemical deposits (cements).

A good rule of thumb is that the magnitude of groundwater flow to mine dewatering systems in fractured-rock settings tends to be higher and more sustained when the flow system is hydraulically connected to saturated alluvial deposits or other unconsolidated materials that have a high drainable porosity. Unconsolidated alluvium typically yields between 10 and 100 times more water per unit volume than many fractured rock types. An exception to this rule can occur when working in regional carbonate settings where there is sufficient regional-scale flow within the fractured rock system itself to sustain high dewatering flows.

Porosity is also a function of the depth of the hydrogeological unit below the ground surface and therefore the total stress that is acting on the unit. Where fractured rock units are encountered at depths of several hundred metres or more below the ground surface, the fracture porosity may be very low (n ≤0.001) beca...