![]()

1

Australian conditions and their consequences

Australia has an extraordinary diversity of birds and a fascinating paleontological history (Schodde 2005a). Because the two may belong inextricably together, they need more than a fleeting mention. Climate and land contribute immeasurably to the way in which an organism can develop, diversify and radiate. Climate, for instance, may force migration or encourage permanent settlement. The land may provide for all needs or only for some of them, or it may be unreliable and fickle in the way in which it can support life and, in this case, animals that stay need to have their wits about them. If climate permits and birds can defend year-round all-purpose territories, then this may have social consequences as well: breeding seasons can lengthen and partners may not need to separate after each breeding season. Unreliable food sources or involuntary exposure to many novel situations exerts pressure which in turn may lead to the evolution of a larger brain because this, as some have argued, may require increased behavioural flexibility and lead to the ability to cope with and respond to novel challenges. Indeed, certain circumstances within climate and landscape may require sophisticated perceptual and cognitively advanced abilities (Amiel et al. 2011). Conversely, if chances of survival are better with a bigger brain and greater cognitive abilities, then time and energy are needed to nurture and support a bigger brain (see Chapter 2) and conditions in the environment need to make this possible.

Hence the question where birds first evolved is crucial. This had been a puzzle for a long time and is not a marginal question or of limited interest only to Australia. To trace species to their origin can, after all, also trace certain traits and expose mechanisms of evolution. It is very pleasing to be able to say at the beginning of this book that the question of the origin of birds appears to have been settled once and for all. In 2004, a very telling American paper was published about the origin of birds (Barker et al. 2004). It made headlines everywhere and had an even more important response within Australia. It showed conclusively that passerines (perching birds comprising true songbirds called ‘oscines’ and sub-oscines, that make up two-thirds of the world’s existing avian species) originated in the parts of Gondwana that comprise present-day Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica (Cracraft 2001; Barker et al. 2004). This was a landmark publication and laid to rest a 200-year controversy between southern and northern hemisphere scholars.

The Australian Museum and researchers, such as Christidis and many other scholars in Australia, had argued for decades that the origin of birds was Gondwana. When interviewed for his response to this publication by the ABC Online science program (Skatssoon 2004), Christidis said that the suggestion that songbirds originated in Australia had been considered ‘ludicrous’ earlier when presented by Australian researchers because, as most believed, Australia did not have that many birds relative to the rest of the world and so it could hardly be central to avian evolution. When Christides and colleagues first presented their results in the 1980s, they were ‘laughed at’ by their northern hemisphere colleagues. ‘Up until the last four or five years it's always been thought that the passerine birds originated in the northern hemisphere and spread south and that's been the gospel for the last 200 years,’ Christides was quoted as saying (Skatssoon 2004).

There was another major finding in 1997, showing conclusively that the worldwide mass-extinction event of 65 million years ago that had wiped out dinosaurs completely, did not end bird life. Indeed, Cooper and Penny (1997) found evidence for a mass survival of birds of at least 22 lineages, suggesting diversification already during the Cretaceous period 141–65 million years ago (Cooper and Penny 1997). Hence, according to this latest understanding, modern lineages did not arise after the mass extinction event but well before it, and knowledge of this then made it imperative to know when and in what sequence the various continents and land masses separated and which living cargo they took with them and which species evolved locally only after the supercontinent split apart.

Because of better technologies and new methods for measurements in the last 15–20 years, all these fields of research just about co-timed their new discoveries in such a manner that they could inform each other, leading to a virtual explosion of publications and new findings in the last 10 years. The very first and significant fossil find in Australia was the discovery by Boles of a songbird fossil carbon-dated as being about 54 million years old (Boles 1995). It is the oldest songbird fossil ever found. The next earliest to it is a recent find in Europe, dated to about 30 million years ago (Mayr and Manegold 2004). Clarke et al. (2005) reported a fossil find in Antarctica that represented the first Cretaceous fossil definitively placed within the extant bird radiation. It was a new species named Vegavis iaai and identified as belonging to Anseriformes (waterfowl) and closely related to Anatidae, which include true ducks. They inferred and concluded that at least relatives of ducks, chickens and ratite birds were living at the same time as non-avian dinosaurs (Clarke et al. 2005). Knowing now that waterfowl and ratites, of which the emu is a descendant (Fig. 1.1), belonged to very old lineages derived from the Australian part of Gondwanaland before separation from Antarctica allows us to trace the evolution of lineages not only along genetic and species lines but also in terms of the evolution of behaviour (to be dealt with in the next chapters).

In 2013, a fossil find of avian footprints discovered among the fossil-rich cliffs of Dinosaur Cove on the coast of southern Victoria caused another media stir (Sci-News.com 2013; Gannon 2013). The researchers think the tracks belonged to a species about the size of a great egret or a small heron (Martin et al. 2014). The find was identified as being about 105 million years old, placing it in the Early Cretaceous period and making this the oldest avian footprints ever found in the world (Fig. 1.2). This places the evolution of birds not merely well within the Cretaceous period but even towards the very beginning of this period.

A further landmark for avian evolution came from genome sequencing. By the end of 2013, the genomes of about 50 mammalian species had been sequenced while those of just seven bird species had been determined. The first was the chicken (Hillier et al. 2004), the second the zebra finch (Warren et al. 2010), followed by the turkey (Dalloul et al. 2010) and, among others, also the peregrine and saker falcons (Wang et al. 2013). In 2014, the budgerigar sequencing was published (Ganapathy et al. 2014) and some impressive genomics comparisons in birds were undertaken covering sequencing of a further 41 bird species allowing new and elucidating comments relevant to taxonomy (Zhang et al. 2014; Jarvis et al. 2014) and brain evolution, specifically with evolution of song and language in mind (Pfennig et al. 2014). No doubt, as a result of these substantial and new analyses, the next decade will bring further insights and new perspectives on avian evolution, diversification and radiation and a whole host of new information. They may even help elucidate how and when certain brain structures appeared in songbirds or even in specific species, such as the cockatoos, that have particularly large brains. We now have the means to probe the links between genes, brain, behaviour, environment and evolution. Indeed, such research has already started (Clayton et al. 2009).

Fig. 1.1. The emu derives from one of the oldest lineages of birds. It is particularly significant as one of the animals on the official crest of Australia. Emus (like other ratites) are unusual in that the male collects and broods the eggs of several females and protects the hatchlings until they can fend for themselves. Indeed, it is a complete role reversal. Females also initiate courtship.

Fig. 1.2. The oldest footprints of a bird (105 million years old) with the feet of an extant species superimposed. Very little change in the design of feet is apparent. The researchers regard the smudges on the left foot as an indication that the bird was just soft-landing from flight. This tantalising thought hints at the possibility that these early modern birds were perhaps not just gliding but had already acquired flight. The left footprint is not unlike that of a lyrebird. (Adapted from lifescience.com 25 Oct. 2013, and sci-news.com and Emory Health Sciences 28 Oct. 2013 online, www.sciencedaily.com)

At least the debate about the local origin of songbirds and many other orders seems to have been laid to rest, but it is worth remembering that this occurred as recently as 2004 and there are many unanswered taxonomical questions yet to resolve. We may well find, also in view of the results of comparative genomics, that some Australian avian species may still be reassigned to a different family or may become their own family in the near future (Christidis and Norman 2010). Investigations into the evolutionary history of birds are aided by better techniques, spectacular new findings and by more data points over many years of a lively taxonomy and paleontological culture in Australia. To this day, native Australian birds are being reassigned and renamed taxonomically (Brown et al. 2008). Moreover, species are still being discovered, mostly at the recent and extremely productive fossil site of Riversleigh in north-western Queensland such as a new parrot, stork, swiftlet and gallinule from the Tertiary to the Miocene (Boles 1993, 2001, 2005a, b, c).

So far confirmed is that, among non-songbirds, ratites, chicken, ducks, pigeons and parrots evolved in that part of Gondwana that includes present-day Australia and New Zealand. And then there are the perching birds, of which there are nearly 5800 species now, constituting 60% of all birds worldwide. Previous genetic studies had already supported the hypothesis that honeyeaters are an ancient radiation within Australasia (Sibley and Ahlquist 1985, 1990; Christidis and Schodde 1991). The earliest lineages to which lyrebirds and scrub-birds, treecreepers, bowerbirds and catbirds belong are thought to have evolved 53–45 million years ago. The next were the bristlebirds, pardalotes, fairy-wrens and scrubwrens about 35 million years ago. As far as we know, thereafter followed Corvida and Passerida. Core Corvoidea include the Australasian centred fantails, birds of paradise, whistlers, magpies, butcherbirds, currawongs, woodswallows, flycatchers, cuckoo-shrikes, orioles and crows. They seem to have evolved about 20 million years ago. By that time, the scleromorphous woodlands were already well established in Australia and increasing aridity and warming, and possibly also deficient soil conditions, low in calcium and nitrogen, changed the flora and encouraged the diversification of scleromorphous woodlands (Groves 1994). It has been argued that the spread of open woodlands and grasslands fostered the existence and spread of Australia’s giant herbivorous ground birds, such as the dromornithids, also called Mihirungs (Murray and Vickers-Rich 2004). Paleoclimate details of the last 250 000 or so years suggest some complex patterns of glacial and interglacial climate shifts with weakening northern monsoon rains. Rainforests receded; the land dried further and vast grasslands spread. The changes harmed some species, specifically the megafauna that became largely extinct, including the Mihirungs (Murray and Vickers-Rich 2004), but it benefited others. For instance, the spread of the family Artamidae and Cracticus (magpies and butcherbirds and allies) has been seen as tied to climatic changes and vegetation type (Kearns et al. 2011, 2013). This information gleaned from the paleontological literature (Christidis and Norman 2010) is convincing evidence enough for me to consider Australia and birds as belonging together and as inextricably intertwined. It is a question what the role of climate changes, innovation and cooperation might have had in them surviving and thriving.

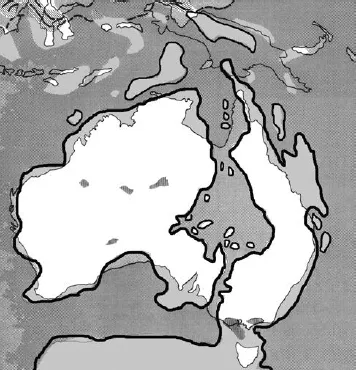

Shape of Australia after break-off from Gondwana and bird life

The date of Australia’s final breaking off from the remainder of Gondwana and the precise shape of Australia as a landmass at the time of its breakaway seem to be relatively uncertain. Around 50 million years ago, well after the mass extinction, the shape of Australia is depicted as something very different in various publications. The Australian continent was nothing like the shape it is today and, to my surprise, I found little agreement as to which part of the continent was, at any one time in its paleogeographic past, really part of the landmass and which was submerged or formed islands. It is very clear, however, that in the Cretaceous period (i.e. in the millions of years when modern birds first evolved) mainland Australia was not one island and not a unified landmass (although it had the potential to be so depending on sea levels), but a myriad of islands because of rising sea levels (Fig. 1.3). Sources seem to agree that rising sea levels caused the large flat part of inland Australia to flood, allowing the sea to invade or even divide eastern and western Australia for probably tens of millions of years. These periods happen to roughly coincide with the now suspected period of evolution of modern bird lineages. Even at times of dominant landmasses, there were two large landmasses that were separated by substantial bodies of water, oceans that were unbroken by land from the north right down to Antarctica at the very time when birds are thought to have evolved (although it is not clear whether some parts of the southern end of Australia were submerged or not). Some publications for the general reader draw maps that are completely land while others draw contours that suggest that the continent was partly split into east and west. The myth of an inland sea may have arisen partly out of the knowledge that sea creatures were found in what is now central Australia and can be seen displayed in Coober Pedy. It is hard to imagine that the land on which Coober Pedy was built – now the opal-mining centre of Australia and very much part of dry and hot inland Australia – was part of the ocean floor 120 million years ago and beyond. If part of the continent had consisted of many islands at the time when modern birds first evolved, this might well be of major significance. We know that oceanic islands drive divergence and speciation, but also have a potential role as repositories of ancestral diversity (Aleixandre et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.3. Australia 110 million years ago (thick black outline). The continent is far from being one landmass – with present-day Australia shown in white. This ‘inland’ sea is called the Eromanga Sea. It has yielded rich fossil finds of sea mammals. (Redrawn and simplified from Laseron 1984.)

Australia, at least for possibly a few crucial tens of millions of years, might have been a thousand islands, not one landmass in which species were readily able to criss-cross the continent. Many islands foster speciation and are said to have had an influence on brain evolution as well (Amiel et al. 2011). And much later, when Australia became one landmass (due to substantial falls in sea levels) and took on a shape similar to that of today, it then sported an appendage that was part of its tectonic plate: namely a land bridge to Papua New Guinea that spanned hundreds of kilometres and created an easy passage for birds to get to South-East Asia and for Papuan species to cross over to Australia. The extraordinary outcome is that the Australian landmass now has different ages in terms of emergence from the water – some areas in Queensland and in Western Australia have always been land but many others have a more recent history.

One of the starkest reminders of the ancient, but variously exposed, parts of the Australian continent are the unique sites in South Australia revealing Precambrian soft-bodied Ediacara Biota, dating back over 500 million years and showing so far the very first evidence worldwide of the emergence of mobile life forms (Gehling and Droser 2012). The fossils found in South Australia were once part of the sea floor. They now give us the first glimpse of organisms that became the template for all viable life forms from invertebrates to humans (Peterson et al. 2008). There can be nothing more ancient in a continent than such finds and these are on Australian soil and part of the patchwork of the current continental shape and composition that may have changed every so often and in significant ways: from land back to sea and back to land. This, as much or more so than even climate change, might have helped shape Australia’s bird life, and all of its other flora and fauna.

In summary, the current shape of Australia is not what it was at the time birds evolved due to: (a) changing sea levels separating parts of Australia from one another; (b) an important land bridge with Papua New Guinea, at least for some time; and (c) a receding coastline. Modern Australia, as a continent, is a patchwork, a quilt of parts that became exposed to become land at various times in prehistory and these phenomena present challenges when attempting to determine the biogeographical patterns of dispersal and diversification in birds (Jønsson and Fjeldså 2006; Schodde 2005b; Kearns et al. 2011).

It is very exciting to think that many passerine birds found along the east coast of Australia, such as lyrebirds, bowerbirds, treecreepers and honeyeaters, are living descendants of tens of millions of years of evolution, and they are not the only ones.

There are places ...