![]()

| 1 | Humans and grasslands – a social history |

| | Beth Gott, Nicholas S.G. Williams and Mark Antos |

RECONNECTION: Grasslands can be a place for traditional owners to engage in cultural practices; here, digging to trial traditional means of increasing Chocolate-lilies (Arthropodium sp.), a traditional food plant. Photo: MCMC CC BY-NC-ND.

Humans and grasslands – a social history

Beth Gott, Nicholas S.G. Williams and Mark Antos

The story of Australia’s grasslands begins when the vast rainforests of Nothofagus (Southern Beech) that covered much of the continent retreated with the cooling and drying of the climate (Hill 2004; Martin 2006). Fossilised pollen from the late Miocene (11–5 million years ago) suggests that in the place of those rainforests came more open forests and woodlands of Eucalypts and Casuarinas, accompanied by grasses and daisies. Fire became common (as evidenced by charcoal deposits), perhaps because of the shift to a climate with seasons, especially a marked dry season (Martin 2006). Repeated large changes in climate drove the trend from closed rainforest to more open vegetation throughout the Pliocene (5–2.5 million years ago) (Hill 2004).

By the beginning of the Pleistocene (2.5 million years ago), the fossil pollen records show that the plant families Asteraceae and Poaceae had increased significantly – suggesting substantial woodlands and grasslands were present by this time, and rainforest was confined to coastal and highland areas (Martin 2006). Megafauna, including now-extinct species of kangaroos and the large herbivore Diprotodon, grazed along the Murray River (Hill & Brodribb 2006). The Pleistocene climate swung repeatedly from cold and glacial to warm and wet. During the coldest periods, the snowline lowered 1000 m in altitude, glaciers formed in the Snowy Mountains and Tasmanian highlands, and temperatures were 6–7 °C cooler than today (Hill & Brodribb 2006). It was also much drier, with mean annual rainfall 100–200 mm lower than today, because moisture was locked in ice caps and glaciers. These conditions allowed extensive areas of cold, dry, open grasslands, termed steppe, to prosper. Some plants developed underground storage roots to survive the harsh seasonal conditions and across south-eastern Australia, drought-adapted deciduous shrubs came to prominence (Hope 1994). Pollen records show that between the cold, dry times, trees increased in abundance and extent.

Humans arrived in Australia in the late Pleistocene 50 000 years ago (Williams 2013), a period that coincides with the extinction of the continent’s megafauna. There is continuing scientific debate about the relative importance of a drying environment versus human hunting pressure in the extinction of the megafauna, but what is increasingly clear is that substantial changes in the vegetation occurred from that time onward. The loss of huge numbers of large herbivorous marsupials is thought to have allowed a build-up of vegetation that led to more frequent fires, recorded by traces of dust and smoke in sediment cores (Lopes Dos Santos et al. 2013), which in turn shifted the vegetation of much of the Murray–Darling Basin towards Eucalypt woodlands and grasslands, the species of which, in turn, are more fire-prone. The relative proportion of spring-growing and summer-growing plants (C3 and C4 plants), inferred from the chemical composition of plant leaf waxes and fossil eggshells of emus and the extinct giant flightless bird Genyornis newtonii, shifted dramatically towards C3 species (Miller et al. 2005; Lopes Dos Santos et al. 2013).

HUNTED HERBIVORE: ‘The West Victorian Aborigines had stories of the Mihirung – the big flightless birds. The one that survived longest and was most widespread was the plant eater Genyornis newtoni, looking like a big robust emu; the Aborigines preserved the story of how it was hunted.’ (Dawson, 1881) Drawing by Nobu Tamura CC BY 3.0.

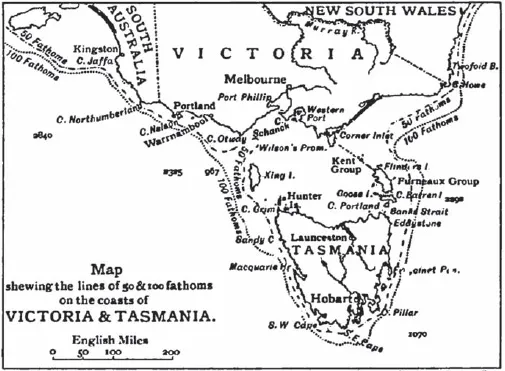

At the peak of the last ice age, 22 000–18 000 years ago, treeless vegetation, grassland and heathland covered most of south-eastern Australia, in places reaching to the coast, with Eucalypts restricted to sheltered areas (Hill 2004). Sea levels were 120 m lower than today and Tasmania was connected to Victoria by a broad expanse of grasslands and open woodlands known as the Bassian Plain that today lies drowned beneath Bass Strait (Petherick et al. 2013). The Victorian Volcanic Plain was a steppe dominated by Poaceae and Asteraceae that has no modern analogues and which varied in composition across the region (Kershaw et al. 2004).

THE BASSIAN PLAIN: Map showing the 50 fathom (91 m) and 100 fathom (183 m) depths in south-eastern Australia. The mainland extended across a substantial land bridge, of grasslands and woodlands called the Bassian Plain, to Tasmania during the last ice-age. From: Alfred William Howitt: The native tribes of south-east Australia, 1904.

When the last glacial maximum ended 18 000 years ago, temperatures and rainfall increased, sea levels rose, and changes in vegetation were rapid. Pollen records indicate that chenopods and daisies decreased in abundance and grasses became more dominant, signifying a shift from steppe vegetation to grassland vegetation similar to that found today (Kershaw et al. 2004). As the climate warmed, Eucalypts and Casuarinas expanded into areas previously dominated by grassland, and for the last 12 000 years (Petherick et al. 2013) grasslands have been restricted to those areas that Eucalyptus, the most ubiquitous of Australian genera, do not colonise due to seasonal drought, cold, heavy soils or animal and human intervention. These areas are the Victorian Volcanic Plain, the Gippsland Plains, the Murray Valley Plains, the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, the Tasmanian Midlands and South Australia’s mid-north. Chapter 2, The native temperate grasslands of south-eastern Australia, details their composition and characteristics.

The Aboriginal People

We do not know for sure when the Aboriginal People first entered the Australian continent from New Guinea and Indonesia, but it was likely that a small founder population, of perhaps 1000–2000 people, were in Australia 50 000 years ago (Williams 2013). It has been suggested that the population remained small across much of Australia until the Holocene (Williams 2013). From 12 000 years ago, when climate stability increased, it is likely that the Aboriginal population increased markedly; Williams (2013) estimates that the population would have been 1.2 million people 500 years ago. They lived in tribal groups which were further divided into land-owning clans bearing the responsibility of ensuring the yield and survival of the resources essential to survival (Presland 2010). Although their way of life has been described as ‘hunter-gatherer’, there was active management of the landscape, depending on oral transmission of the deep knowledge of the country and its flora and fauna which they had accumulated over thousands of years. Their management of the landscape relied largely on the skilled use of fire (Gott 2005).

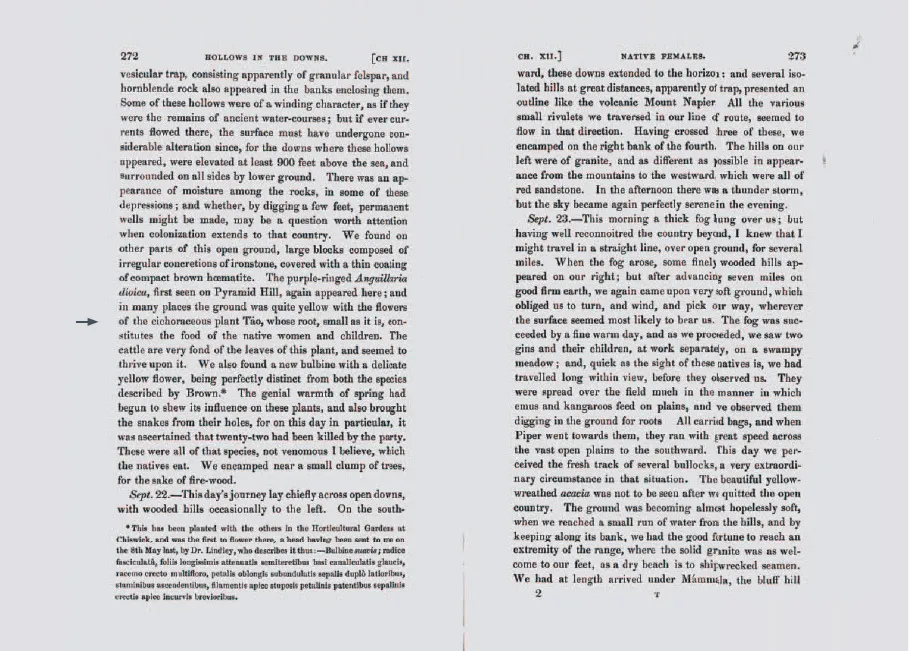

MYRNONG: Mitchell’s 1839 journal where he mentions the species believed to be Microseris lanceolata.

Grasslands as food source

The open grasslands were attractive to grazing by kangaroos and other animals that provided meat, but amongst the grass were also many non-grass plant species known as forbs that provided food to Aboriginal people. The life histories of these species consist of leafy growth during the cool wet part of the year, autumn and winter, during which the energy-rich carbohydrates produced by photosynthesis are stored in underground organs such as tubers, bulbs, corms and rhizomes. As the summer becomes hot and dry, the above-ground parts of the plant die back and the plant avoids the unfavorable dry summer by remaining buried in the soil as storage organs. These underground organs were an important food source for Aboriginal people (Gott 1982; Clarke 1985). Plant food, gathered by women and children, was estimated to make up at least 50 per cent of Aboriginal people’s diet (Winter in Bride 1898; Latz & Green 1995). When hunting was unsuccessful, these storage organs and roots were the fallback food. ‘They depend for food almost entirely on animals and roots’ (Dawson 1881); ‘their natural food consists of the meat of the country when they can kill it, but chiefly roots’ (Winter in Bride 1898).

Taking either the general checklist for the whole of the Victorian Volcanic Plain, containing 550 species (Willis 1964), or the list for the grasslands of the Keilor Plains area (Sutton 1916), 20 per cent of the plants are recorded as being used by the Aboriginal people for food, and half of these food sources are underground storage organs. Notable among the species used were the many perennial lilies and orchids (Gott 1982, 1983, 1993).

Some species were very abundant. George Augustus Robinson, the Protector of Aborigines from 1839 until 1849, noted in 1840 that the basalt plain known as Spring Plains was covered with ‘millions of Murnong [Microseris lanceolata]’ (Clark 1998), a dandelion-like native daisy, the tubers of which were a major staple food (Gott 1983). In 1841 he described women ‘spread over the plain as far as I could see them, collecting [roots] – each had a load as much as she could carry’ (Clark 1998). Major Thomas Mitchell in 1836 described the view south and east from the Grampians as ‘a vast extent of open downs’, ‘quite yellow with the flowers of the cichoraceous plant tao [Microseris lanceolata] whose root, small as it is, constitutes the food of the native women and children. The cattle are very fond of the leaves of this plant and seemed to thrive upon it’ and ‘we observed them [natives] digging in the ground for roots’ (Mitchell 1839).

Grass seeds were hardly eaten at all in temperate grassland regions, although they were staples in the more arid regions of Australia (Dawson 1881). Storage roots have the advantage of being available year-round, unlike the seasonal seeds and fruits. Roots often provided more than starch: ‘Many of them, including the popular Murnong, have a storage carbohydrate made from fructose units (fructan), which does not raise the level of glucose in the blood, as s...