eBook - ePub

Of Vets, Viruses and Vaccines

The Story of the Animal Health Research Laboratory, Parkville

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Of Vets, Viruses and Vaccines

The Story of the Animal Health Research Laboratory, Parkville

About this book

The story of the Animal Health Research Laboratory must be seen against a background of rapid domestic, global and techno-scientific change. During its sixty year history, it made a crucial contribution to improving the standard of Australian livestock, furthered the cause of animal health generally and helped to promote the cause of science to the wider community.

For these reasons and many more, it deserves to be recognised and remembered; this history is an attempt to do just that.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Of Vets, Viruses and Vaccines by Barry W. Butcher,Barry W Butcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Building a Scientific Tradition: 1926–96

Acknowledgments

So many people have given generously of their time to assist me in writing this particular section of AHRL’s history that it is almost impossible to do justice to them all here. Mention must be made of those who answered my often naive questions, responded to telephone calls and read particular sections; without their assistance this writer would have committed some very egregious blunders indeed! I thank them all collectively as I do those who agreed to be interviewed for this project. Some others must be mentioned by name. Heather Mathew, Len Lloyd, Carl Peterson, John Dufty, Trevor Bagust and Jenny York acted as the AHRL History Committee and read and often re-read drafts of chapters. They showed a patience with the author which was over and above the call of reasonable duty; Heather provided many extra services that allowed the research and writing to proceed much smoother than it might otherwise have and I thank her for doing so. Mike Rickard encouraged the project from the start and has been a keen contributor of information and opinion. Rodney Teakle at the CSIRO Archives in Canberra worked wonders in making available documents that were crucial to the early chapters of this history. I would also like to thank Deakin University for allowing me the time to undertake the research for this project. To all I offer my thanks and my hope that the end product is found to be satisfactory.

Barry W. Butcher, 16 September 1999

Introduction

‘Give me a laboratory and I will raise the world’. So wrote the sociologist of science Bruno Latour in relation to Louis Pasteur’s strategy for winning the approval of the French farming community for his scientific work on anthrax. According to Latour, Pasteur needed to demonstrate the viability of his discoveries in a real world situation—in this case a farm—while at the same time knowing that in order for his work to succeed he needed to be able to control the conditions under which it was undertaken.1 Pasteur’s dilemma highlights the problem scientists have encountered since the ‘scientific revolution’ began in the sixteenth century: how to gain respect for their work from a sceptical public audience and how to convince that audience that the strangely artificial world of the laboratory is the best way of understanding the ‘world out there’.

To the extent that they have succeeded in overcoming the problem, scientists bask in their role as the arbiters of knowledge in the modern world; to the extent that they have failed, they must endure the continuing image of the white-coated, bespectacled, usually male, absent-minded ‘nerd’ represented in countless novels and films. Further reflecting this ambivalence, they are often held up as a new priesthood, with science becoming the oracle of truth and the laboratory the modern version of the temple. With such an array of contradictory images it is little wonder that the relationship between science and its public is best defined as uneasy.

There are ways out of this dilemma, and the best place to start is probably the laboratory itself. A little reflection will show that the temple analogy is unsustainable. The temple is the place where knowledge is jealously guarded and where truth is usually taken to be unchanging. However conservative scientists may be, the very techniques and methodologies they employ ensure that the knowledge they create is constantly under scrutiny and that the ‘world out there’ is always in danger of being re-made in the light of new findings in the laboratory. This is a point well understood a century ago by Pasteur, then as now demonstrating that it was the perceived efficacy of the ‘new knowledge’ which lay at the heart of science’s public success.

The point of this short philosophical diversion is to put some context into the writing of laboratory histories, a context which will render them more interesting to the general public, to show, if you will, the social role of the laboratory as it affects the economic and political health and development of the nation. While such histories will have an obvious appeal to those who have been associated with the laboratories in question or to those who work or have worked in similar surroundings, they have rarely been attractive to a wider audience. As a consequence, the importance of science to the public good centres on the impact of its ‘discoveries’, a term which itself suggests immediacy rather than the slow and laborious development that characterises the history of scientific advance.

In Australia historians have shown a scandalous disregard for the role that science has played in the development of the continent since European settlement in 1788, and this notwithstanding some spectacular success stories that could and should be told. As a nation Australia has built its wealth and identity on agricultural development, and since the late nineteenth century much of that development has proceeded due to the work of scientists of all kinds who have toiled long and hard to improve the output of producers. A few have achieved a notable public image— William Farrer for the breeding of new strains of wheat, for instance—but most have gone largely unrecognised. The average citizen would be hard pressed to name one of the small band of Australian Nobel prize-winners, let alone any of the world renowned veterinarians who have time and again come to the aid of Australia’s livestock industry, often working away for years under-financed and under-recognised before finally achieving any meaningful breakthrough.

It is against this background that the first section of the history of the Animal Health Research Laboratory at Parkville is written. These introductory chapters do not focus on the technical details of particular research programs, something best left to those whose individual expertise can be found in the contributions in the second half of this volume. Rather, I have attempted to sketch a word picture of the historical development and life of the laboratory as a locus of scientific activity, with all the institutional and cultural interest that designation implies. This approach necessitates recognising that more goes on in the laboratory than strict attention to experimentation, method and technique; those white-coated figures have personalities that both enhance and transcend their scientific skills. Indeed, part of this section of the history of AHRL is predicated on the belief that from its inception in 1938 the laboratory was fashioned and re-fashioned in line with the differing attitudes of the Divisional Chiefs. Some stand out for their vision and personality and for their direct impact on the direction of research and the general philosophy of AHRL. This is not to deny or decry the efforts of other Chiefs; it simply reflects a reality fashioned by changing political and financial conditions. As Alan Pierce, for one, candidly admits, he arrived to take up his position in 1966 when money was no object and the political climate was ripe for change and expansion; some of his successors had fewer of those luxuries to work with and so their impact on the Division was more severely circumscribed. Other factors, of course, play a role in changing the face of AHRL during its sixty years of existence. Innovative technologies, coupled with the explosion of information in post-World War II biological sciences, made it possible to open new fields of research and new approaches to old research problems. At the same time the rapid growth of livestock industries such as poultry and pigs broadened the scope for new research.

In the post-war years the place of the nation in the world changed; improvements in the speed of travel increased the number of international linkages, drawing AHRL more tightly into the net of global science. Ironically, as such ties strengthened old ones slackened. The inter-war years were a period when co-operation was seen in a strongly Imperial context, and the task of the colonial and Dominion scientist at the geographic periphery was to follow the lead set by the established scientific institutions at the Imperial centre. It was UK scientists and administrators who were headhunted by the leaders of CSIR in the 1920s and 1930s, and it was to the UK that Australian scientific graduates travelled to gain further recognition for their skills. Once World War II was over and Britain, having lost its Empire, found itself looking for a new role, the scope for imported expertise broadened out, and while the UK remained the place of choice for many Australian science graduates, increasingly they looked further afield to the USA and Europe. Australian scientists soon found themselves seconded off to far-flung areas of the globe as advisers to colonial and post-colonial Governments in Africa and Asia; the Division of Animal Health was well represented in this diaspora.

In summary then, the story of AHRL must be seen against a background of rapid domestic, global and techno-scientific change. During its sixty-year history it made a crucial contribution to improving the standard of Australian livestock, furthered the cause of animal health generally, and helped to promote the cause of science to the wider community. For these reasons and many more it deserves to be recognised and remembered; this history is an attempt to do just that.

Reference

1 Bruno Latour, ‘Give Me a Laboratory and I Will Raise the World’, in K. Knorr and M. Mulkay, eds. Science Observed: Perspectives on the Social Study of Science, Sage, Los Angeles, 1983.

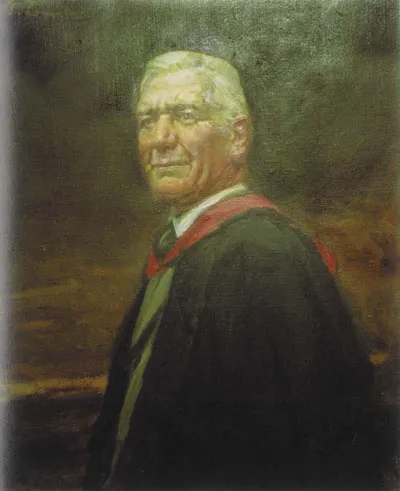

John A. Gilruth, MRCVS, DVSc, FRSE, Chief of Division from 1930 to 1935. Portrait by Sir John Longstaff, 1935.

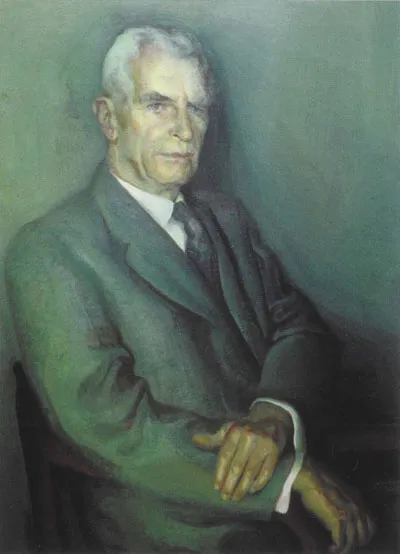

Lionel B. Bull, CBE, FAA, DVSc, FACVSc, Chief of Division from 1935 to 1954. Portrait by Murray Griffin, 1954.

Chapter 1

The Making of the Division, 1926–37

Anything which adversely affects Australia’s great pastoral industry strikes at the very roots of the country’s wealth and prosperity. That is why the various diseases and disorders affecting the health and productivity of our flocks and herds are a vital national concern.

Ten Years of Progress 1926–1936, CSIR, Melbourne 1936.

The move to set up a scientific organisation dedicated to undertake research into Australia’s primary industries has been traced in some detail by Currie and Graham in their history of the origins of CSIRO.1 From 1910 until the formation of CSIR in 1926, there were three Commissions of various kinds—largely concerned with the issue of applied scientific research. In 1913 there was also an important report by Thomas Brailsford Robertson that urged, among other things, that substantial resources be dedicated to scientific investigation into problems associated with the agricultural and livestock industries. Events moved frustratingly slowly, however. An over-enthusiastic and unfulfilled promise of £500,000 for scientific research, by Prime Minister William Hughes in 1916, and the formation of the insufficiently funded Federal Institute of Science and Industry in 1921 did little to spur on the pace of research in Australian science.

Despite the oft-repeated claim that in the early years of the twentieth century ‘scientific research’ usually meant agricultural research, most of this was undertaken in State agricultural institutions, and in the main was concerned with improving the quality of plant crops. The great names were William Farrer, whose celebrated ‘Federation’ wheat strain represents one of the high points of Australian agricultural research, and the Victorian plant pathologist Daniel McAlpine, who carried out valuable investigations into the causes of rusts in wheat and potatoes. The livestock industry could point to no such names or to such spectacular successes in the first two decades after Federation. At the conference organised by Hughes in 1916, attention was drawn to ‘the sheepfly problem’ with a call that priority be given to research into this scourge of the wool industry, but little was done to take up the challenge of a disease then costing wool growers a substantial amount each year. The problem of continuing inaction on the research front was further highlighted in the 1920s when an innocuous disease—‘worm nodules’ in beef—led to a ban on Australian beef by the British health authorities. Later in the same decade, lamb and mutton exports were also curtailed when caseous lymphadenitis (‘cheesy gland’) infestation was found to be almost endemic in exported Australian meat. In 1923 buffalo fly and Kimberley horse disease were added to the list of animal health concerns causing major losses to the livestock industries/All this at a time when these national industries were earning an average of £140 million a year—over 60 per cent of total agricultural output.

Not until the visit of Sir Frank Heath in 1925, to advise on the direction and structure of Government involvement in science, did the issue of livestock research begin to gather momentum. Heath followed Brailsford Robertson in urging more investigation of livestock problems, and drew attention to the poor quality of breeding stock in both sheep and cattle industries. His comments appeared to be well timed. At the Imperial Economic Conference held in 1923 a resolution had been passed allocating £1,000,000 to the Dominions to assist in the efficient production and marketing of primary produce, and Australia was well placed to take advantage of this instance of ‘Empire co-operation’. Once again, this was in line with suggestions made at the 1916 conference that Empire-based research should be encouraged. But if Heath’s visit provided the spur, his specific recommendations were not carried through: in particular, the suggestion that the Federal Government should set up a number of scholarships for trainees in fields directly related to Australian research problems. When CSIR finally came into being in 1926 it consisted of five Divisions, and Animal Health was one of these. Everything was far from plain sailing at this early stage, however, for there was little understanding of how to organise research so as to get the maximum benefit for producers. There was also little agreement as to how ‘animal health’ was to be defined, and strong, on-going tensions between CSIR and State agricultural departments jealous of their own fiefdoms and concerned at the prospect of greater competition for limited research funding.

From the beginning, there were no ready-made facilities. CSIR scientists worked from the facilities of the Veterinary Research Institute in Parkville, within a Divi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Significant Dates and Events

- Part One: Building a Scientific Tradition: 1926–96

- Part Two: Research Activities

- Appendix 1: Animal Welfare

- Appendix 2: Staff List

- Contributors

- Index