- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dragonflies of the World

About this book

Here, for the first time, is a comprehensive and accessible overview of one of the world's most popular insect groups, the Odonata. Written for interested amateurs as well as more experienced professionals, Dragonflies of the World covers their evolution, ecology, behaviour, physiology and taxonomy. It describes their unique attributes and the distinctive features of the suborders, superfamilies, families and subfamilies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dragonflies of the World by Jill Silsby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The reaction of most people, when an insect approaches them, is to make an involuntary exclamation and swiftly swipe it away. We have learnt, often to our cost, that bees and wasps have stings, mosquitoes and midges bite and that the sooner such creatures leave our vicinity the happier we will feel. The fact that the majority of insects neither sting nor bite leaves us supremely unmoved and many totally innocuous creatures are swatted by nervous humans as they buzz harmlessly by.

Dragonflies, in particular, seem to inspire fear and, indeed, they could be said to have a somewhat ferocious appearance. Many have an inquisitive nature and their large size, together with the audible clatter of their wings, can understandably cause alarm. In the past dragonflies were known as ‘Horse-stingers’ and ‘Devil’s Darning Needles’. However, all fears where these insects are concerned are groundless: they have no sting and their powerful jaws are incapable of doing us — or horses! — any harm. On the contrary, in more ways than one, they are beneficial to humans: their presence at a piece of water indicates that the water is not polluted; they have voracious appetites and, since they are solely carnivorous, they consume vast quantities of insects that can cause us annoyance or, even, actual harm. There have even been projects where dragonfly larvae were released into domestic water-storage containers in order to suppress the pre-adult stages of disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Libellula incesta (Slaty Chaser).

Dragonflies and damselflies — the Order Odonata — are among the most beautiful and interesting insects on earth and the purpose of this book is to show how valid that claim is. As the pages are turned, so their beauty will become evident and the variety of their often intriguing behavioural patterns will unfold.

Odonates are also among the most ancient of Earth’s living fauna and, before looking in detail at the families flying today, we should attempt to get some idea of just how long they and their ancestors have been around. It will help first to put them in context with other creatures and to take a brief look at the planet on which they all evolved. We will examine the divisions of geological time and see what was about in the relatively recent periods.

Serious questions regarding the age of our planet have exercised enquiring minds for the past three or more centuries. One of the first calculations made was that of James Ussher in 1654. He came up with the date 4004 BC. His conclusion, which commanded great respect, was reached by studying the genealogical verses in the Book of Genesis and the date was accepted without question by the majority of those living at the time and, indeed, by their descendants for well over 100 years to come. There were, however, people who studied the earth, its mountains and valleys, its rocks and rivers, its plateaux and its oceans. Seashells were found on the tops of mountains which seemed to prove that high land had once been the sea floor; bones were discovered that had clearly belonged to creatures that were no longer found on Earth. Such discoveries, and many others, gradually forced scientists to reject Ussher’s date in favour of a very much earlier one. Suggestions as to the real age of the earth varied enormously and ranged from hundreds of thousands of years to thousands of millions. Today it is reckoned that Earth is around 4600 million years old.

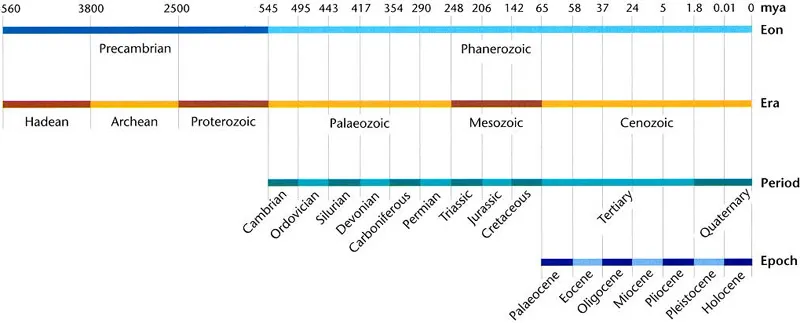

The divisions of geological time.

Life existing during in Precambrian times was, generally speaking, unicellular and fossils have only rarely been found in the sedimentary rocks laid prior to the Phanerozoic. In 1946, however, the fossilised remains of some extraordinary multicellular jellyfish-like creatures were discovered in the 550-600 million-year-old Precambrian rocks of the Flinders Ranges in South Australia and were named Ediacara fauna, after the mine in which they were excavated. More ediacaran fossils have since been found in rocks of similar age in other parts of the world and recent scientific work hints at even earlier multicellular forms. The origins of life are continually being pushed further and further into the dim and distant past.

Phanerozoic time extends from the end of the Precambrian until the present day and is represented by rock strata that contain clearly recognisable fossils. It is divided into three Eras: Palaeozoic, meaning ‘Ancient Life’; Mesozoic,‘Middle Life’ and Cenozoic,‘Recent Life’.

Palaeozoic era

The Cambrian period covered the first part of the Palaeozoic era and during that time several marine invertebrates, particularly trilobites, flourished. A trilobite is a very early arthropod (a creature possessing a segmented external skeleton that is divided into three parts). Modern representatives of the phyla which started to appear in the fossil record of this period include worms, corals, crabs, shellfish, sponges and centipedes.

The Ordovician period, lasting 50 million years, saw the proliferation of marine invertebrates and the appearance of the earliest fish.

During the Silurian period, which lasted for 40 million years, marine life (with the exception of mammals and amphibians) was partly as we know it today.

In the lower Devonian strata the first amphibians appear and the upper strata contain evidence of the ‘conquest of land’. A few fossil (wingless) insects are also present in these strata.

Fossils of the Order Protodonata (Chapter 12) first appear in rocks of the Carboniferous, the period that saw Earth’s coal deposits laid. Among these are members of the family Meganeuridae which included the giant Meganeura monyi. It is probable that from one of these 300+ million-year-old insects are descended all the odonates that fly today. Fossil remains of primitive cockroaches and mayflies are also present, although the latter are very rare.

In the Permian deposits, which were laid some 285 to 245 million years ago (mya), fossils of the Order Protozygoptera have been found.

Mesozoic era

This, the ‘Middle Life’, began some 245 mya and is known as the ‘Age of the Dinosaurs’. In Britain, Jarzembowski has found fossil remains of modern Anisoptera, Zygoptera and Mesozoic ‘Anisozygoptera’ dating from this era.

During the Triassic, the first of the Mesozoic periods, reptiles flourished (including a few small carnivorous types of dinosaur). The first ‘modern’ dragonflies (of the suborder Anisozygoptera) appear.

The Jurassic saw the supremacy of the dinosaurs. There were pterosaurs, not birds, in the air. It is in the strata of this period that fossil ammonites are found and also, in addition to the earliest mammals, the first Hymenoptera (solitary bees and wasps but, according to Jarzembowski, no social species) and Lepidoptera (moths but, according to the same source, no butterflies). Fossils of Aeshnidae, Gomphidae and Petaluridae make their first appearance in these layers.

During the Cretaceous period chalk deposits were formed, flowering plants first evolved and birds flew. The broad-winged damselflies (Calopterygoidea) appear here. The larger and best-known dinosaurs did not survive the end of this period but a number of other groups did, for example crocodiles, turtles and birds. The boundary between the end of the Mesozoic era and the beginning of the Cenozoic was marked by what is known as a ‘mass extinction’ and is known as the K/T line.

Cenozoic era

The last of the three eras (Recent Life) is also known as the Age of the Mammals. Rocks deposited at the commencement of the Cenozoic show evidence of dynamic change to the planet. During the earlier Cenozoic periods there is evidence of tropical palms in southern England but the end of the era heralded a much cooler climate. It was not until the Cenozoic, which began just 65 mya and takes us up to the present day, that mammals gradually became dominant. During the deposition of Cenozoic strata, many older forms of life became extinct and recent species of both animals and plants took their place. Hoofed mammals appeared some 39 mya and by 7 mya many of our modern animals were flourishing. As in the case of the previous two eras this one is also divided, this time into just two periods:

A model built from a reconstruction (drawn by Wolfgang Zessin) of Namurotypus sippelli(wingspan 32 cm). The fossil was recovered from strata laid 325 mya in Germany.

The Tertiary period began 65 mya and lasted for around 63 million years. The period is divided into five further rock series that are known as epochs and, since they are often used when referring to fossil deposits, it will be useful to note their names. The Palaeocene was characterised by the appearance of placental mammals and, by the end of the epoch, primates had evolved. The Eocene rock strata show the rise of the mammals; rodents and whales were among the groups to make their first appearance, and the first monkeys. It was not until this epoch that libelluloid dragonflies appeared. Oligocene strata began to be laid about 35 mya and the Epoch was characterised by the continued rise of the mammals; pigs, rhinoceroses and tapirs, for example, made their appearance, and the first apes. Miocene strata are characterised by the appearance of fossilised grazing animals and Afropithecines (early hominoids).

The spread of grasses was responsible for many important ecological changes. The Pliocene is the last of the sedimentary deposits laid down in the Tertiary period. It is characterised by the appearance of modern plants and animals, and the first Australopithecine (early hominid).

The Quaternary period began approximately 1.8 mya and is made up of two epochs, the Pleistocene and the Holocene. The former is the earlier and is characterised by the alternate procession and recession of northern glaciers (Ice Ages) and, the first appearance of Homo sapiens and the Neanderthals, although the advent of hominoids has been traced much earlier, to the Tertiary. Holocene strata are still being laid today.

Odonates lived alongside the Jurassic dinosaurs some 200 million years ago; and insects not so very different from them were flying 100 million years before that, when the ancestor of all the dinosaurs was just a small, reptile-like creature somewhere in a Carboniferous rainforest. Odonates were here before some of our ancient mountains arose and before the continents separated into the landmasses we know today. They witnessed the appearance and disappearance of the dinosaurs, the arrival of the birds and the evolution, just yesterday, of the human race.

SURVIVAL

The question is often asked, ‘Why did dinosaurs disappear?’. It is an interesting question and many answers have been put forward to account for their extinction. One is that a gigantic meteorite crashed into Earth with dire consequences for much of the animal life on the planet. Another suggests that a series of explosive eruptions on the earth’s surface had similar consequences. Others suggest that all but a few species were unable to adapt to, or escape from, periods of global warming, or of advancing glaciation. It has even been mooted that dinosaurs failed to survive the Flood because they were too big to get into the Ark! Present research indicates that one or other of the first two answers is the right one.

An equally interesting question is, ‘Why did odonates survive?’. That can be answered by posing another question, ‘Why does anything survive?’. Darwin provided an answer to that when he published his well known theory regarding ‘the survival of the fittest’. Creatures survive because they adapt to make the best use of a changing environment. As we have seen, the end of the Mesozoic era was marked by a mass extinction that only a very few creatures managed to outlive. Dinosaurs (apart from birds) were among the many groups that succumbed but odonates were one of a few that survived and their ‘fitness’ to do so (in the context of Darwin’s theory) is largely due to a couple of very different factors.

First, during their lifetime odonates experience two totally different life styles. In almost all cases, the egg and larval stages are spent in water whilst the adult stage is an aerial one. Following emergence from their larval casings, the newly winged insects instinctively fly away from the water, dispersing into the neighbouring countryside and sometimes travelling very considerable distances. This dispersal period has been a vital factor in odonate survival. Over the millennia, should one piece of water have dried up or turned into ice, or should a river have changed its course, odonates were able to find suitable re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Today’s Odonata

- 3. Life cycle

- 4. The perfect hunting machine

- 5. Lords of the air

- 6. Colour and polymorphism

- 7. Territory and reproduction

- 8. Habitats and refugia

- 9. Odonata around the world

- 10. Evolutionary riddles

- 11. Artificial rearing

- 12. Conservation

- Glossary

- Dragonfly societies

- Bibliography

- Index of species

- General index