![]()

Project Vesta1 is Australia’s most recent and significant study of forest fire behaviour. The study derives its name from the Roman goddess ‘Vesta’ who tended the sacred hearth. Project Vesta has investigated the behaviour and spread of summer bushfires in dry eucalypt forest with different fuel age and understorey structures. The seven-year project was initiated in 1996.

Research Aims

The four main scientific aims of Project Vesta were:

• To quantify the changes in the behaviour of fire in dry eucalypt forest as fuel develops with age (i.e. time since fire).

• To characterise wind speed profiles in forest with different overstorey and understorey vegetation structure in relation to fire behaviour.

• To develop new algorithms describing the relationship between fire spread and wind speed, and fire spread and fuel characteristics including load, structure and height.

• To develop a National Fire Behaviour Prediction System for dry eucalypt forest.

These aims have been addressed through a program of experimental burning and associated studies at two sites in the south-west of Western Australia.

Background

Fire behaviour guides for eucalypt forests were first developed in the early 1960s by Alan McArthur of the Commonwealth Forestry and Timber Bureau (1962, 1967), and George Peet of the Western Australian Forests Department (1965). These guides were developed from measurements of small experimental fires lit in open eucalypt forest with fuel composed of leaf litter and occasional low shrubs. Fires were generally ignited at a point and allowed to develop for periods of up to one hour or so. These models were designed primarily to predict the behaviour of fire for prescribed burning operations, but were extrapolated to predict the behaviour of high-intensity fire using observational reports of spread of wildfires.

Preliminary analysis of the behaviour of high-intensity fires burnt during Project Aquarius and work by Burrows (1994, 1999b) suggested that at high wind speeds, these models consistently under-predict by a factor of 2 or more. In the past these under-estimates have been attributed to more fuel burning under wildfire conditions or to the unpredictable effects of spotting (McArthur 1967). Spotting was clearly not a factor contributing to increased spread rates during the Aquarius experiments (CSIRO unpublished data) and the errors in prediction are more likely to be due to the experimental techniques used by McArthur and Peet to build the models. Case studies of wildfires have also shown that existing guides tend to under-predict rate of spread and fire intensity, particularly under more severe burning conditions such as occurred in south-eastern Australia on Ash Wednesday in 1983 (Rawson et al. 1983).

There is a universal need for a better understanding of forest fuel and how it determines fire behaviour – particularly under severe weather conditions. This is required not only to build better models to predict fire spread at a local or regional level, but also to evaluate the impact of fuel reduction burning to reduce the behaviour of wildfire burning under severe conditions.

Prescribed burning to reduce fuel load and modify the behaviour of wildfire has long been promulgated through Australia as a basic fire protection strategy in eucalypt forest. Each year more than 650,000 ha of forest land are prescribed burnt at a cost of over $6.5 million.

The reduction of wildfire behaviour immediately following fuel removal by burning is obvious: there is no surface fuel to burn, and crown fires collapse within a few metres of the perimeter of the burnt area. Reduction in fire behaviour in subsequent years is not so obvious.

Case studies into the operational effectiveness of fuel reduction by prescribed burning rely heavily on anecdotal evidence, and the effect on wildfire behaviour was clearly evident for only 3 years (Underwood et al. 1985). In Victoria, wildfire was shown to be effective in reducing the behaviour of subsequent wildfire under extreme weather for 5 years but in at least one case there was no discernible difference in fire behaviour 18 months after prescribed burning (Rawson et al. 1985). The differences were attributed to very high fuel-removal in the first case, and to poor operational standards resulting in a suspected low proportion of the area actually prescribed burnt in the second.

A systematic analysis of interaction between wildfire behaviour and such factors as vegetation types, weather conditions, and fuel characteristics as modified by prescribed burning has never been possible due to the unplanned and chaotic nature of wildfire events. There are always uncertainties about the fuel load on prescribed burnt areas at the time of the wildfire. These arise due to uncertainties about the areas actually burnt during the operation, the fraction of fuel removed and the subsequent rate of fuel accumulation. Accurate measurement of rates of spread and wind speeds during the wildfire are almost unattainable on comparable sites.

Although expert opinion strongly supports prescribed burning to reduce the impact of wildfire (Cheney 1996; Lewis et al. 1994), public opinion is quite divided. Conservation groups point to apparent failures and are aware of the lack of solid scientific and statistical evidence to support a reduction in fire behaviour beyond 2–3 years after burning (Meredith 1988). It has even been argued that hazard reduction burning may actually enhance the propagation of wildfire by promoting shrub regeneration in areas which may otherwise have inherently low fire-prone characteristics (Anon. 1994).

Fuel load is the only fuel characteristic used in Australian fire danger rating systems to predict fire behaviour within a particular fuel type. Studies by McArthur (1962, 1967) and Peet (1965) suggested that the amount of available fuel on the forest floor (i.e., the fuel consumed by the fire) was the most significant fuel variable affecting the behaviour of fire in eucalypt forest. The authors claimed that the rate of spread of the head fire (R) is directly proportional to the load of fine fuel (< 6 mm diameter) consumed (w) and is expressed as a simple linear relationship:

R = aw

where ‘a’ is a constant defined by McArthur (1962) and Peet (1965).

Fire intensity is defined as the rate of heat released per unit length of fire front (Byram 1959). It is expressed as units of ‘kilowatts per metre of fire front’ and is defined by the following equation:

I = HwR

where I = fire intensity (kW m–1),

H = the heat yield of the fuel (kJ kg–1),

w = load of available fuel (fuel consumed) (kg m–2) and,

R = rate of forward spread of the fire front (m s–1)

The relationship between fuel load, rate of spread and fire intensity has provided a simple but powerful argument to support fuel reduction practices in eucalypt forest in Australia for more than 30 years. If the rate of spread is directly proportional to fuel load, it is argued that reducing the fuel load by half, halves the rate of spread and reduces the intensity of the fire four-fold (McArthur 1962, Peet 1965).

However, there is very little published data to demonstrate a direct relationship between rate of spread and fuel load. McArthur’s (1962 and 1967) and Peet’s (1965) publications contain no detailed descriptions of methods or statistical analysis with confidence limits on correlations between rate of spread and fuel load. Their relationships were obtained from fires of very low intensity and there is little evidence to suggest that this relationship holds true for fires of high intensity.

Practical observation of experienced fire fighters is that there is changed fire behaviour and increased ease of suppression following fuel-reduction burning. However, these reports are anecdotal, and this change has not been quantified for large fires of high intensity. There are also anecdotal reports claiming no reduction in wildfire behaviour on fuel-reduced areas.

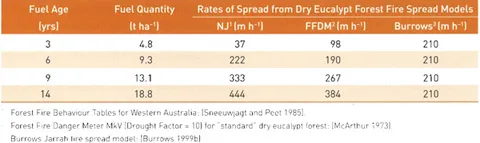

There is considerable uncertainty about how fuel characteristics affect fire behaviour with or without fuel reduction, particularly under extreme fire weather (Cheney 1990). Cheney et al. (1993) found that rate of spread of the head fire was not correlated with fuel load in uniform grass swards that had been harvested to different levels to change fuel loads. Burrows (1994, 1999b) concluded from a series of 2-ha experimental summer fires in jarrah forest that fuel load did not influence the forward rate of spread of the head fire. There is quite wide disagreement between fire spread models for dry forest fuel, and the difference in predicted spread rates widens as the amount of available fuel increases (Table 1.1).

Fire spread studies in homogeneous fuel in a wind tunnel have identified a number of fuel characteristics that influence fire spread (Rothermel 1972). Some agencies have used fire-spread models based on these studies for planning purposes but they have not been widely accepted in Australia. The individual parameters are difficult to define in natural fuel and impractical to measure. The model did not predict well in relatively simple grass fuel (Gould 1988), and very poorly in eucalypt fuel (Burrows 1999b). The practice of building artificial fuel models to adjust parameters so that a reasonable fit to field data could be made (Burgan and Rothermel 1984) was rejected in Australia because it assumed that the relationships established in the wind tunnel could be transferred directly to field fires, and it did not predict the changes that could occur by manipulation of the fuel bed, say by prescribed burning.

Eucalypt litter fuel is not homogeneous. It can be stratified into a relatively compacted horizontal surface fuel layer with an aerated, less compacted layer above; in some fuel types the strata are quite distinct, e.g. shrubs and grasses over litter. It is easy to observe how discontinuities in the surface litter layer (e.g. a narrow fire trail) can stop a low-intensity fire while a high-intensity fire may sweep across the same discontinuity, seemingly without impediment. While the continuity (patchiness or clumps) of the aerated fuel layer is difficult to define, there is increasing evidence that characteristics of this layer, including continuity, bulk-density, and fraction of green material have a significant influence on fire spread. For example, in regrowth forest of silvertop ash (E. sieberii) the rate of spread of low-intensity fire was directly related to the continuity of the aerated fuels (the near-surface fuel layer), which were composed of shrubs, grasses and suspended litter above the surface litter layer (Cheney et al. 1992).

Table 1.1 Predicted rates of spread for different fuel quantities where temperature = 30°C, relative humidity = 30%, wind speed at 1.5 m = 5.5 km h–1, surface fuel moisture content = 5% and slope = 0°.

The apparent increase in fire rate of spread with increasing fuel load demonstrated by McArthur (1967) in fuels of different age might not be due to the fuel load, but rather to a range of structural factors such as height, composition, continuity and greenness which change as fuel re-accumulates after burning. P...