![]()

1

Melbourne

In 1860

Background to the Victorian Exploring Expedition

In the 1850s the gold rush in the newly formed colony of Victoria turned Melbourne into one of the richest cities in the world. The population exploded with an influx of migrants and the harbour bristled with ships. By 1860 Melbourne’s population had grown to 125 000, making it the largest city in Australia. It was a time of confidence and growth and Melbourne acquired a host of grand buildings, including Parliament House, Treasury and the Public Library. There was also a surge of interest in science and discovery which saw the establishment of the University, Museum, Observatory and Herbarium.

In 1854 the Philosophical Institute of Victoria was founded. Three years later they decided to organise an expedition to cross Australia, and in November 1857 they appointed an Exploration Committee to investigate the feasibility of the proposal. The Institute’s plans were boosted in August 1858 when a Melbourne merchant (later identified as Ambrose Kyte) made an anonymous offer of £1000 towards the expedition, providing the public donated an additional sum of £2000. An Exploration Fund Raising Committee was established to raise the money. At the same time, the Victorian government sent George James Landells to India to purchase camels.

The Institute received a Royal Charter in 1859 and became the Royal Society of Victoria.

In January 1860 the Exploration Committee published its Fourth Progress Report, announcing they had raised £2184 and thereby securing Kyte’s offer. They were now ready ‘to make all the necessary preparations for the immediate equipment of an exploring party on the arrival of the camels’. The Victorian government had already paid £5497 to purchase and transport the camels and it voted an additional £6000 grant be made available for the purposes of exploration.

The camels arrived in Port Phillip Bay aboard the SS Chinsurah in June 1860. After being unloaded they were exercised along the beach and then paraded through the city. Huge crowds gathered and the Age remarked ‘it seemed as though all Melbourne had turned out to gaze upon … the novel importations’. Melburnians suddenly became excited about their upcoming expedition.

Preparations for departure

A few days after the camels arrived, the Exploration Committee met and selected Robert O’Hara Burke as Expedition leader. As this was the first Australian expedition to use camels, the Committee thought it was necessary to secure Landells’ services and he was appointed second in command.

One of the Exploration Committee’s many aims was a scientific investigation of the hitherto unexplored centre of Australia. Consequently, three additional officers were appointed to scientific roles. William John Wills was third in command and ‘Surveyor, Astronomical and Meteorological Observer’, Dr Ludwig Becker was the ‘Geological, Mineralogical and Natural History Observer’ and Dr Hermann Beckler was the surgeon and ‘Botanical Observer’. Georg Neumayer, another prominent scientist, joined the VEE at Swan Hill and travelled with them as far as the Darling. Each of the scientific officers was given very detailed instructions on what observations to take, what data to record and what specimens to collect.

The Exploration Committee advertised in the Argus for ‘persons desirous to join the expedition’, and received 700 responses. Burke interviewed 300 people in a day, but most of the nine ‘Expedition assistants’ appointed were men he was already acquainted with. Four of the eight sepoys who had come from India with the camels were also selected to accompany the Expedition.

The camels and sepoys moved from their temporary home at the Parliament House stables to Royal Park on Saturday 7 July, and a week later three Expedition assistants – Henry Creber, Patrick Langan and William Patten – were employed to start assembling the stores. On Thursday 2 August six Expedition assistants moved into tents at the park and five days later, all nine assistants were camped out under the supervision of the foreman, Charles Darius Ferguson.

Beckler and Dr William Gillbee of the Melbourne Hospital subjected the men to a medical. The Argus reported:

Farewell celebrations

The first formal farewell was held on Friday 17 August when the Governor, Sir Henry Barkly, visited the Expedition’s camp:

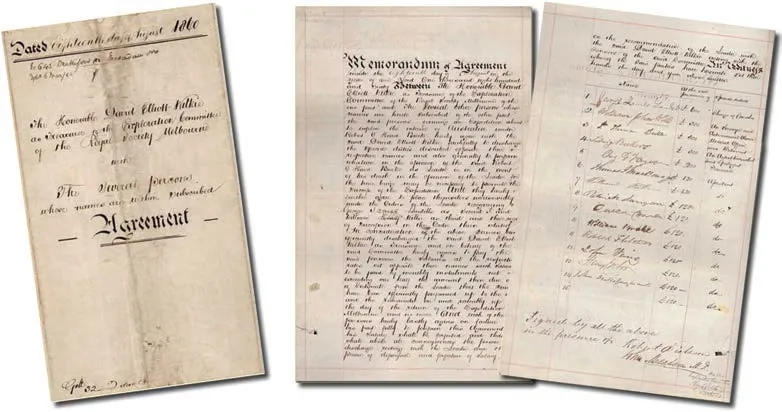

The following day a special meeting of the Royal Society of Victoria was held, when the men came down to the Society’s hall to sign the Memorandum of Agreement. Burke ordered the men fall in and they were addressed by the Society’s president, Sir William Stawell, about

Memorandum of Agreement, 18 August 1860.

Map Case 5 Drawer 6a, MS 13071, Records of the Burke and Wills Expedition,

Australian Manuscripts Collection, State Library of Victoria.

the necessity of ‘cheerfully and unhesitatingly’ giving ‘the most implicit and absolute obedience’ to Burke.

That evening the Melbourne Deutscher Verein held a ‘conversazione’ (a farewell dinner) which was attended by Burke, Wills, Neumayer, Becker and Beckler. The packed room drank toasts and commemorated the German involvement in the exploration of Australia, and ‘the meeting did not separate until a late hour’.

On Sunday Burke attended St James Cathedral when the Dean of Melbourne, Reverend Hussey Burgh McCartney, held a special service to ‘implore the Divine blessing’. While McCartney was entreating Burke ‘to seek Divine Protection, and pray that they, like Hagar, might find a well of water in the wilderness’, there was conflict back at Royal Park. Landells accused Creber of drunkenness. Creber protested his innocence and one of the other men, Fletcher, supported him. Burke dismissed both men.

Burke made numerous personnel changes during the course of the expedition, hiring new men and dismissing members of the initial party. Biographies of all the explorers involved in the Expedition can be found at followingburkeandwills.com.

Now

Burke and Wills Monument

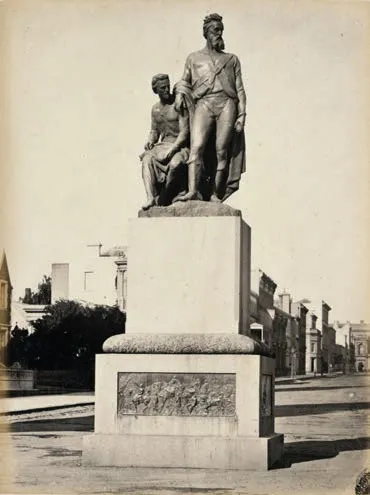

The Burke and Wills statue was Melbourne’s first public monument and was unveiled in 1865.

When news of the deaths of Burke and Wills reached Melbourne in November 1861, former Chief Secretary John O’Shanassy announced that ‘every mark of respect should be shown to their memory … by the erection of a suitable monument, commemorative of achievements so well calculated to advance the cause of science and civilization’. Richard

Monument of Burke and Wills, Melbourne, c. 1870–80.

H31510/16, State Library of Victoria.

One of the four bas-reliefs depicting scenes from the Expedition: ‘Howitt’s Rescue of King’.

Heales, Premier of Victoria at the time, agreed that there should be ‘a permanent memorial to the leader of the expedition and his fallen comrades’.

Sculptor Charles Summers wrote to O’Shanassy explaining he had prepared a design for the monument, and a preliminary drawing of his design was printed on the front page of the Illustrated Australian Mail on Christmas Day 1861.

In February 1862 the government placed £4000 on the estimates ‘to finance the construction of a monument’. In November 1862 the Victorian Government Gazette announced the commission of the sculpture would be decided by a Board of Design. The Board requested that clay or plaster models of ‘a Group of Statuary on a Pedestal’ be submitted within two weeks. Five entries were received and Charles Summers’ design was chosen unanimously. Summers’ winning design was described as ‘Wills (modelled after Michelangelo’s Giuliano de Medici in Florence) seated beside a standing Burke, whose cloak linked the two figures’.

The statue was placed on two blocks of Harcourt granite at Collins and Russell Streets on 29 March 1865. On 21 April 1865, the fourth anniversary of Burke and Wills’ return to the Dig Tree, the monument was unveiled to great acclaim. The floral moulding of passionflowers and ngardu was added in January 1866 and the four bas-relie...