![]()

1

Introduction

Millions of hectares of temperate woodland and billions of trees have been cleared from Australia’s agricultural landscapes (Walker et al. 1993; Lindenmayer et al. 2010a). While this has facilitated the development of areas for cropping and pastures for livestock grazing, it also has had significant environmental impacts. These include rising water tables and secondary salinity, soil erosion, and losses of native plant and animal species. These environmental effects also have had significant negative impacts on farm-level productivity and ultimately profitability of farming enterprises. Restoring some of the native vegetation cover is one of the key ways to tackle these major environmental (and often financial) problems.

This book focuses on why restoration is important and describes some of the latest science about how to most effectively restore farms, primarily for different groups of animals, particularly birds, mammals and reptiles. Much of the focus of this book is on tree plantings, with reference to shrubs and undergrowth. This is for good reason; most problems with the loss of native plants and animals, rising water tables, increased soil erosion, and falling farm productivity correspond directly or indirectly with long-term losses in tree cover. Another focus of the book is on farm wildlife. This is because it has been the target of nearly 20 years of our research at The Australian National University on the effectiveness of restoration plantings (or replantings) for biodiversity. By far the most work we have done has been on temporal patterns of change in wildlife, and especially populations of birds. This has been the case because many farmers have a strong interest in birds, but also because birds can be coarse indicators of the recovery of other elements of biodiversity (Lindenmayer et al. 2014; Ikin et al. 2016a) (see Box 1.1). There is therefore a bias towards birds throughout this book.

Box 1.1. The call of the Clamorous Reed Warbler

‘Warty-warty-warty-creep-creep-creep’ is the call of a small and rather non-descript bird – the Clamorous Reed Warbler – that is closely associated with reeds and other vegetation at the margins of rivers, ponds, lakes and other waterways. The bird features in the title of a book on ecologically sustainable farm management by Charles Massey (Massey 2017). One of the reasons that the bird features in the title and in sections of the book is because its presence reflects, in part, the quality of waterways and water storage on a farm. This, in turn, is a coarse indicator of aspects of sustainable farming. That is, well-managed streams, dams and wetlands where farm management allows the recovery and maintenance of reeds and other riparian vegetation have a high probability of also supporting populations of the Clamorous Reed Warbler. Good management of ‘the wet bits of a farm’ is usually then a good reflection of the water-retaining ability of the land on a farm with corresponding benefits for livestock, particularly during drought periods. The Clamorous Reed Warbler is a seasonal migrant in southern Australia, arriving in September–October to begin breeding, so gauging the quality of habitat for the species requires surveys for the species at the appropriate time of the year. Of course, not all birds are good surrogates for farm management, and birds tend to be only crude indicators of the persistence of other groups of animals (such as reptiles) (Ikin et al. 2016a). Nevertheless, the distinctive call of the Clamorous Reed Warbler is one of the positive signs of good farm management.

In the last 5–10 years, there have been major new insights into what makes effective replanting programs. These insights have been derived at the same time as there has been a marked increase in the amount of native vegetation cover in some regions of south-eastern Australia, particularly central and northern Victoria and southern New South Wales. Some of these changes have been due to natural regeneration (e.g. post-drought recovery and post-fencing recovery along streamside areas), but other changes are a direct outcome of extensive and intensive revegetation programs. We have been fortunate to have been able to not only track changes in the amount of vegetation but also to document how biodiversity has responded to these changes.

There is no doubt that while revegetation programs have been important, new science shows there are ways to maximise their effectiveness. This book aims to bring some of that science together in one place. We have attempted to do this in a simple and sequential way. Our second chapter summarises some of the key reasons why restoration programs are important – why do a replanting? Chapter 3 examines what to plant. This is followed by a discussion in Chapter 4 of where to plant. Once a planting has been established, it will often need to be managed and this is the primary topic of Chapter 5. Nothing in nature is static, including plantings and in Chapter 6 our focus is on how plantings change through time.

Box 1.2. The potential consequences of doing it wrong – a key reason to write a book about plantings

One of the lessons from our long-term studies of plantings is that it is possible to establish plantings that can have a negative impact on biodiversity. As an example, the narrow plantings often one to three trees wide of exotic trees such as Cyprus Pine that have been established on some farms can actually create ideal habitat for exotic pest bird species such as the House Sparrow and European Starling. Native tree and shrub species are more likely to be colonised by native birds. We suggest it is far better to use native plant species, particularly those local to the broader region to establish plantings. Similarly, our field surveys show that very narrow plantings, especially those lacking an understorey and which are heavily grazed, tend to be dominated by the Noisy Miner (Fig. 1.1) – a despotic hyper-aggressive native species that bullies other birds (Grey et al. 1998; Montague-Drake et al. 2011; Mac Nally et al. 2012). Our work suggests that, rather than creating more habitat for this problematic species, wide plantings (with four or more trees) with some understorey will be a deterrent for the Noisy Miner and provide habitat for many other species of native birds (Lindenmayer et al. 2010b).

Figure 1.1. A narrow planting and the Noisy Miner. Planting photo by Damian Michael, Noisy Miner by Graeme Chapman.

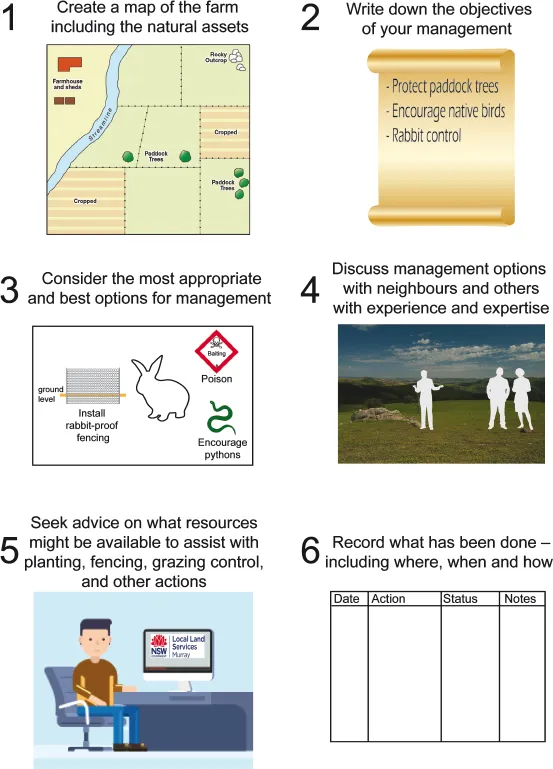

Figure 1.2. Conceptual diagram of the sequence of steps in considering, designing, establishing and then managing a replanting.

The final chapter of this book explores some general themes, including the need for farm planning, and links between farm restoration and the importance of monitoring for documenting the effectiveness of restoration programs.

The chapters that follow are what we (and many colleagues) believe to be a logical sequence for a farmer or resource manager to think through the process of designing and then establishing a replanted area. The sequence of steps is shown in Fig. 1.2. This is a very linear way of approaching the challenge of establishing a replanted area on a farm. However, we recognise that a great many people have already been working to restore parts of the vegetation cover on their land and may benefit more from later chapters in the book, such as those on how to manage an already established planting or what to anticipate might be the changes in a planted area over time.

Where have the insights in this book come from?

Almost all of the information in this book is based on insights we have derived from the past 20 years of intensive field research. Our work aims to answer key scientific questions of applied management relevance, many of which are asked by farmers or staff from management agencies such as Local Land Services and Catchment Management Authorities. For example, how wide should a planting be to provide habitat for birds? Are older plantings more likely to be colonised by reptiles than young plantings? Do plantings with nest boxes support more species of native hollow-using mammals than plantings without nest boxes? A robust study design is needed to unequivocally answer these questions and considerable time is spent with statistical scientists ensuring that the work is completed at the highest possible standard. Once a study is designed, research and monitoring are conducted by expert field-based ecologists located permanently in regional Australia, and who complete many thousands of measurements on hundreds of hectares of plantings from central Victoria to south-east Queensland. The data that are gathered are then subjected to exhaustive and robust statistical analysis by a team of highly trained statistical scientists. The results of analyses of field data are then written up by all involved as scientific articles and submitted for publication to scientific journals where they are subjected to intense scrutiny under the peer review process (see Box 1.3).

There is some research in this book from our long-term studies which we have not yet published in scientific journals. An underplanting study within old growth woodland that lacks a shrub layer (see Box 3.2 in Chapter 3) is one of several examples. Our hope is that these studies will soon be finalised and the results more widely communicated to both our scientific colleagues and on-the-ground practitioners of restoration programs.

Box 1.3. Scientific ‘peers’, the peer review process and the quality of published science

The validity of scientific research is regularly ‘road-tested’ in the brutal world of scientific peer review. The concept of ‘peers’ in fields like politics is one in which a group of colleagues look out for each other, sometimes in somewhat less than ethically appropriate ways. Peer review in science is the extreme opposite when it comes to the assessment and publication of scientific articles. Reviewers work as hard as they possibly can to find flaws in work that is submitted to a good scientific journal, and they demand that the standard of research is lifted to as high a level as possible. Peer review is usually anonymous and criticism can be fierce; it is not a process for the faint hearted or those weak in spirit and persistence. Some journals reject at least 90% of articles that are submitted to them and a paper will often need to be started afresh when it is rejected. In the ecological sciences, the average paper might go to four or five journals before it is not rejected outright. Even then, a non-rejection may still require that the paper undergo major and repeated revisions before it is finally accepted. This process of submission, rejection, revision and acceptance may take two or three years and sometimes much longer. Almost all of the 100+ scientific papers that underpin this book have experienced this kind of brutal treatment in the peer review process. Peer review is a rigorous process that few non-scientists understand or appreciate, but, in general, it means there are relatively few poor quality articles in good quality scientific journals.

Box 1.4. Why science is important

A key part of applied ecological science is that it aims to better understand ecosystems in ways that lead to better land management. There are myriads of examples of why and how this can be important. A sobering but important example is that of the Wedge-tailed Eagle, rabbits and lambs. Hundreds of eagles used to be shot because they were perceived to be predators of lambs. Photographs of dead birds draped over barbed wire fences were common and one of us (DBL) still recalls this sight from early childhood. There is no doubt that lambs are sometimes taken by eagles. However, detailed scientific studies revealed that rabbits, and not lambs, are the main prey for the Wedge-tailed Eagle. Moreover, hunting of rabbits by birds of prey means less competition between sheep and rabbits for food, leading to better outcomes for farmers in terms of paddock productivity. In this case, robust scientific evidence highlighted the benefits of native wildlife for farmers.

Some of the other benefits of replanting on farms

While much of this book focuses on the responses of animals to replanted woodland vegetation, we are acutely aware of work on the value of restored areas in contributing to overall farm productivity and positive financial outcomes (Walpole 1999; Bird et al. 2002; Massey 2017). There is also preliminary anecdotal evidence to suggest that there are positive relationships between restoration efforts and mental health; that is, farmers engaged in active restoration on their farms have found it to be beneficial to their mental health. We touch on some of these key (and sometimes somewhat unexpected) benefits of restoration programs in the final chapter of this book. Work on the intersection of restoration science, farm finance, and farmer well-being is complex, challenging and in its infancy, but it is our aim to report further on the results of that important multidisciplinary work in next 5–10 years (the amount of time it will take to confirm the multifaceted benefits derived from restoration programs on farms). This exciting new research is being enabled, in part, by the Sustainable Farms initiative at The Australian National University, launched in 2018.

Some notes about this book

Much has been written about revegetation and there are some excellent guides on the topic. We also have written extensively in the past on woodland restoration (e.g. Lindenmayer et al. 2011; Munro and Lindenmayer 2011; Lindenmayer et al. 2016c). Our aim here is not to rehash previous work so that we can lay claim to have written another book. Rather, a lot of new scientific work has been published in the past five years, resulting in the new ideas and results that we are featuring in this book. The majority of that work currently appears in scientific journals that few people read (including scientific colleagues) and which are simply inaccessible to people with a broad interest in restoration and wildlife on farms.

Communication of science is critical and through this book we have sought to create a way for practitioners with interests in establishing plantings in agricultural areas to access our research. In fact, one of the primary motivations for writing this book was that many farmers and resource managers have repeatedly asked us over the past f...