![]()

1

Introduction

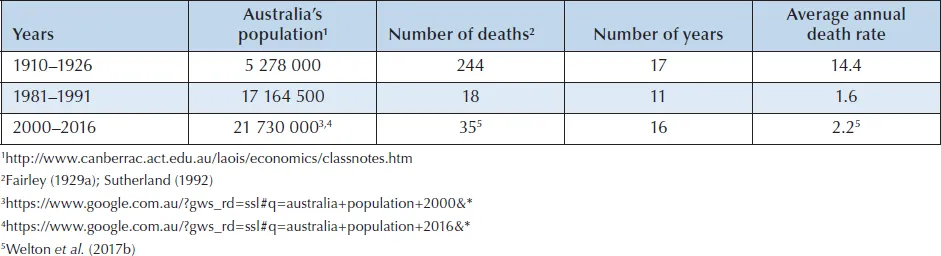

During the early days of the European settlement of Australia, snakes were abundant, and many snakebites occurred. The first antivenom for a medically important Australian elapid snake – tiger snake antivenom – was developed in 1930. Subsequently, in response to public pressure, other antivenoms were produced: taipan antivenom in 1955; brown snake antivenom in 1956; and death adder antivenom in 1958. The need for additional antivenoms was then recognised, and further products followed: Papuan black snake antivenom in 1959; sea snake antivenom in 1961; and the polyvalent in 1962 (Brogan 1990). The decline in numbers of snakebite deaths (Table 1.1) has been due to the introduction of antivenoms, ever improving knowledge of and use of better first aid, improved medical awareness and care (especially intensive care procedures such as mechanical ventilation), a public better educated about snakes, and also probably due to the decline in snake numbers, especially tiger snakes (Mirtschin et al. 1999). Snakebite has remained at about the same frequency over recent years, despite increases in the human population (Sutherland 1992; Sutherland and Tibballs 2001).

In 21st century Australia, many snake species have declined, and it appears as though the average size of individuals within many species has declined as well. In Australia, as in most countries, over the last century there have been innumerable changes to most habitats placing great pressures on many snake species. A few species may have benefited from these changes (e.g. because of increased availability of rodents attracted to human dwellings), but most have declined. The major environmental pressures that have most affected various snake populations include: direct habitat loss through land clearing; habitat modification caused by grazing domestic animals; coral bleaching and the concomitant loss of large populations of marine animals; introduction and presence of feral animals; loss of prey species; application of herbicides and pesticides; the impact of pest plant species; and probably global warming as well. The net effect of these pressures has caused a downward spiral in populations of most native animals that has not yet been halted, or even detectably slowed. Increasingly, global warming threatens to pose an evergrowing threat. If recent geophysical analyses prove correct, global warming threatens to further alter habitats in drastic ways, thus probably forcing the extinctions of many species.

Table 1.1. Decline in snakebite deaths in Australia.

Currently, medically important (‘dangerous’) snakes occupy all habitats of the whole of the mainland, Tasmania and many offshore islands, with sea snakes occurring in coastal waters around the northern half of Australia. In most habitats, there are more than one dangerous snake species. Even urban environments in our major cities have snake populations, and it is surprising to see how some species manage to fit into highly modified environments. Sea snakes occur in waters off two of our capital cities and off a number of the larger coastal provincial cities.

Interaction between humans, domestic animals and snakes inevitably occurs, and some people are gradually becoming more tolerant of co-existence with snakes, and even enjoying their presence. Australia manufactures some of the best antivenom in the world, and also has a medical fraternity who are quite well versed in snakebite management. There are now a number of recurring and regularly updated courses and symposia, which focus on the detailed topic of medical treatment of snakebite. This has contributed to the development of an emergency medical system and retrieval services that have improved capabilities to handle life-threatening envenoming from highly venomous Australian elapid snakes.

Our knowledge of some snake species has grown over the last 25 years, and cumulatively now represents a solid foundation for future management of some species threatened with possible extinction (e.g. Hoplocephalus spp., broad-headed snakes). In contrast, for many other species, vital knowledge about even their basic natural history is still lacking and represents a challenge to wildlife conservation agencies. For instance, studying the ecology of a species such as the inland taipan, Oxyuranus microlepidotus, presents real hurdles due to its isolation. Tiger snakes, once a very common species, are now in serious decline, and yet there is much to learn about their natural history. Their insular populations offer a tantalising opportunity to study a single snake species adapted to a diverse set of habitats. However, sometimes interest in expanding our knowledge of venomous snakes may arise from an unexpected source. With the growing demand for various seafoods, and the associated large harvests from the sea, some funding from seafood industries has been allocated to investigate the impact on sea snakes. Whether viewed as self-serving, or not, this has facilitated further study, and added to the basic knowledge about the ecology and ethology of several sea snake species. Nevertheless, the basic biology and natural history of most species of these enigmatic snakes has hardly been studied.

The conservation of Australian venomous snakes is of real concern, and in most cases it cannot be separated from general environmental losses and considerations. The challenge for future generations will be to wisely allocate funds for objectives that will yield the greatest benefits to most species. In this book, we have tried to generally describe the greatest threats to the irreplaceable populations of many of these snakes, and encourage efforts to protect their long-term survival. It is imperative that governments recognise the inherent value in protecting all of Australia’s unique wildlife – even the irrationally maligned venomous species. Government agencies must also ensure that their efforts are clearly focussed on major threat reductions.

In Chapter 7 and Appendix 1, we also outline the history of venom collection associated with antivenom development and consider venoms, and some representative examples of the modern applications of their components. It is important to appreciate that the journey of some of Australia’s pioneering amateurs and professionals who interwove their lives with snakes in order to learn about their behaviour, biology and venoms. Many of these early workers took great risks by working with some of the world’s most venomous species, and several paid the ultimate price with their lives. Although most of us have an inkling of the potent toxicity of some venoms, there is relatively limited recognition of the positive uses of these venoms. In cancer research, haematology, neurology, cardiovascular medicine and inflammatory diseases, venoms are used either for research, diagnostics or occasionally as therapeutic agents. A small handful of snake venom-derived components have been developed into important medications, and have been added to the pharmacotherapeutic armamentarium against human diseases.

When we are confronted by a snake, given a photograph of one, or find a dead one on the road, determining its identity will no doubt present a challenge for some of us. Many will use the coloured photographs in the book and combine them with the range maps of the snakes to determine the most likely identification. This can be sufficient, and this book contains many colour and pattern variations to compare with a specimen or photo. Some of the more studious will approach the identification more systematically, and use scale counts by following the diagrams provided. If this is insufficient, we have provided identification keys, which may help those willing to attempt more formal taxonomic identification. This can only be done if the snake is available, and it is safe to do so. For those not proficient in snake handling, counting scales on live snakes should not be attempted.

Treating snakebite is largely a specialised area of medical practice, and ideally best reserved for those skilled in this specialty (clinical toxinology). Fortunately, in Australia, the aforementioned highly specialised courses and workshops conducted by experts in this field have contributed to the distribution of a handful of knowledgeable people among most Australian states. Even so, it is best that seriously envenomed victims be transferred to a large emergency unit or intensive care ward as soon as possible. The first-response to snakebite is included in this book, as is discussion of the latest methods and criteria needed to effectively and compassionately handle an envenoming emergency.

Reptile houses are often the most visited exhibits in any zoo, and snakes are the primary attraction. This is not because they are ‘loved’, but often because people are drawn and fascinated by animals they interpret as ‘deadly’. For interested readers who don’t like snakes, we hope this book helps change that view to some extent. If this book manages to help some readers appreciate the value of having snakes in the environment, whether it be simply in the scrub or even in suburbia, then a major intention of this work will have been achieved.

![]()

2

The relative danger of snakes

Snakebite and envenoming: a global perspective

Just how ‘dangerous’ are snakes? In reality, only a relatively small number of potentially medically important snakes are ‘dangerous’ when harassed, inappropriately handled or accidentally contacted by an unsuspecting human. However, a number of medically important venomous species persist around agriculturally worked locations in several tropical regions, and thus unfortunately constitute a significant public health problem in several countries. In order to compare Australia’s potentially medically important snakes proportionally with those in other geographic regions, it is useful to briefly consider medically important snakebite from a worldwide perspective.

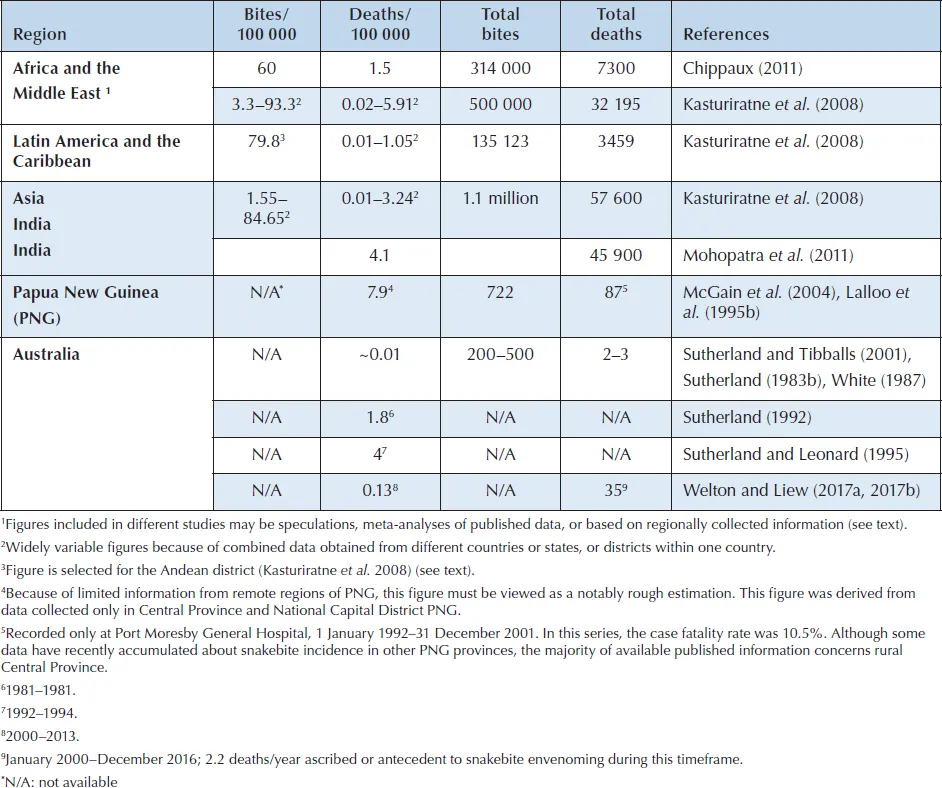

Global estimates/speculations of morbidity and mortality from snakebite envenoming consist of mostly crude approximations because of limited documentation. Aside from recent speculations of worldwide mortality between 100 000 and 200 000+, the true numbers of persons affected by permanent disabilities as a consequence of snakebite envenoming, remain largely unknown. Below are some estimates, and comments about their limitations, of the incidence of snakebite envenoming in several representative regions in which snakebite is a significant public health problem. Table 2.1 summarises some of the figures included in several published studies that have assessed snakebite incidence.

Africa and the Middle East

In a meta-analysis of documented reports, Chippaux (2011) estimated 60 snakebites/100 000 persons with an approximate average of 314 000 envenoming and 7300 deaths (1.5 deaths/100 000 persons), while Kasturiratne et al. (2008) reported a higher estimate of approximately 500 000 persons envenomed annually (depending on region, 3.33–93.34 snakebites/100 000 persons), with a high estimate of 32 195 fatalities (0.018–5.909 deaths/100 000 persons); the highest burden was in West Africa. Chippaux’s analysis also suggested that 95% of snakebites occurred in rural areas, as did 97% of fatal outcomes. The average envenomed victim was a male agricultural worker/farmer around 18–22 years old (Chippaux 2011).

As these figures are derived from published information and/or general estimates, it is clear that they are essentially ‘educated guesses’, and may over- or underestimate the actual incidence. Cautiously, with all factors considered, these approximations are more likely underestimates because of the likelihood of underreporting from rural locales, which constitute the main regions with substantial snakebite burden (de Silva et al. 2013). Also, it is likely that a significant number of envenomed victims do not present to medical facilities because of fear, superstition or local dependence on ‘traditional healers’.

Latin America and the Caribbean

The recent speculations about global incidence included regional assessments of snakebites and related mortality with subsequent high and low estimates. These speculative estimates pinpoint other regions where snakebite envenoming figures as a serious public health problem. For example, Kasturiratne et al. (2008) also reported high estimates of 135 123 snakebites for all of Latin America and the Caribbean, with 3459 deaths (depending on region, 0.008–1.05/100 000 persons). The highest snakebite incidence/100 000 people, was in the Andean region of Latin America, and Panama had a particularly notable annual snakebite incidence (79.8/100 000) (Kasturiratne et al. 2008). The highest snakebite mortality/100 000 people, was in the Caribbean region. As noted in the overview for other regions, these speculations are very likely gross underestimates.

Table 2.1. Estimates and speculations about the annual global incidence of snakebite, and comparison of geographic regions.

Asia

The estimates of snakebite in this very large geographic area containing marked venomous snake diversity also support the perception of snakebite envenoming as a serious, and underreported, public health problem. Comparison of two studies can provide a sense of the difficulties in assessing the true scope of this problem, the limitations that plague acquisition of accurate global snakebite data, and the judicious care that must be exercised when considering published estimates. Kasturiratne et al. (2008) performed a literature-based analysis, and thereby derived speculations about the regional incidence and mortality from snakebite envenoming. Their high estimates for Asia in total (including the Asian Pacific region) suggested >1.1 million annual snakebite envenoming (depending on region, 1.55–84.65/100 000 persons) with some 57 600 deaths (depending on specific region, 0.010–...