![]() PROCESSES

PROCESSES![]()

3

Fuel, fire weather and fire behaviour in Australian ecosystems

Andrew L Sullivan, W Lachie McCaw, Miguel G Cruz, Stuart Matthews and Peter F Ellis

Introduction

It is difficult to understand the ecological impact of fire without sound knowledge of the range of fire behaviour that can occur in a given ecosystem. The rate of energy release, flame characteristics, residence time and rate of spread of a fire can vary greatly depending upon the ignition pattern, weather, vegetation and topography in which a fire occurs. The mode of combustion of the fire – that is, whether it is heading, backing or flanking – also influences the behaviour and subsequent impact of the fire.

This chapter discusses factors that influence the behaviour of fires in three key vegetation types: those dominated by grassy fuel such as open grasslands, woodlands and open forests with a grassy understorey; dry sclerophyll eucalypt forests dominated by a leaf litter surface layer with or without a dominant shrub understorey; and mallee-heath shrublands. Although the morphology of these ecosystems is very different, the effects of topography and weather on fire behaviour are similar for all vegetation fires.

Climate and fire weather

Fire climate of Australia

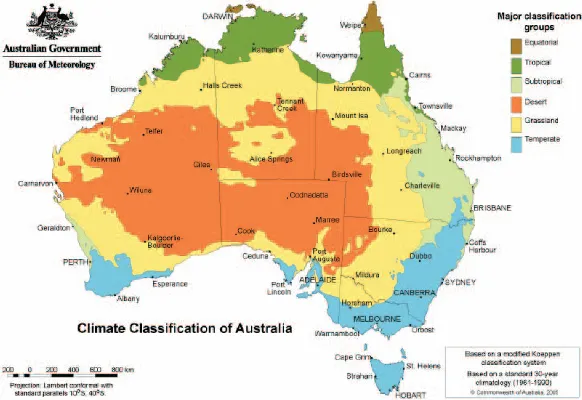

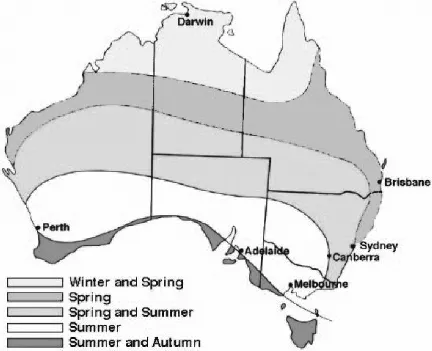

At any time of the year it is fire season in some part of Australia. The Australian Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology divides Australia into six climate groups and 28 classes (Stern et al. 2000) using a modified Köppen scheme based on temperature and the amount and timing of rainfall (Figure 3.1). For fire management, it is more usual to use the scheme of Luke and McArthur (1978), which recognises five broad zones of fire season (Figure 3.2), characterised by the seasonal occurrence of fuel dryness and conditions conducive to the ignition and spread of fires in the landscape. Russell-Smith et al. (2007) proposed an alternative classification of fire season in Australia based on seasonal fire occurrence and rainfall over a 7-year period.

The climate in the tropical north (latitude <23°S) is primarily determined by the annual monsoon season (which may include cyclones), which extends from November/December through to March/April (the wet season). The remainder of the year is characterised by warm, dry conditions (the dry season). The fire season in the north is defined by the period during which the savanna, the predominant biome, becomes fully cured and will burn readily, and generally lasts from April/May to the commencement of the wet season.

Figure 3.1. Six key climate groups for Australia based on a modified Köppen classification system. (Source: Stern et al. 2000, Bureau of Meteorology product code IDCJCM0000, used with permission)

Figure 3.2. Fire season in Australia moves south as the year progresses. In northern Australia, the peak fire season occurs during winter and spring. In southern Australia, the fire season does not occur until summer and may extend into early autumn. (Source: Luke and McArthur 1978)

Southern Australia generally experiences peak fire season in the summer months because of the combination of cool winters and warm to hot summers, with rainfall predominantly in winter and spring. In some parts of the country (e.g. south-west Western Australia) there is a pronounced seasonal summer/autumn drought, while other areas (e.g. Tasmania) have year-round rainfall. However, rainfall in the temperate parts of Australia has considerable interannual variability connected with oceanic climate cycles, particularly the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) (Pittock 1975). In El Niño/drought years, fuels are drier for extended periods of the year, and days of elevated bushfire potential are more common than in non-El Niño years (Williams and Karoly 1999). Normally arid central Australia can experience relatively wet years that result in abundant short-lived vegetation growth and elevated fire risk as a consequence.

Fire weather

The primary surface meteorological variables that govern fire behaviour are wind, rainfall, air temperature, relative humidity and solar radiation. Wind indirectly and directly affects fire behaviour through its effect on fuel drying, combustion and rate of spread (see the ‘Fire Behaviour’ section). Small-scale variability in wind (i.e. turbulence) also affects fire behaviour (Albini 1982): thermal updrafts and downdrafts help to spread firebrands and change direction of spread (e.g. Sun et al. 2009), and local variation in wind speed induces variation in rate of spread and combustion processes (Sullivan 2007).

Temperature, relative humidity and solar radiation determine the transfer of water vapour into and out of fine dead fuels, controlling the short-term moisture content. High solar radiation, high temperature and low humidity result in low fuel moisture content.

Rain affects fire behaviour by raising the moisture content of dead fuels above their extinction moisture content, thus impeding combustion (Pickett et al. 2010). This effect may persist for a few hours (e.g. standing grass), or seasonally (e.g. deep litter fuels, coarse woody fuels). Rainfall cycles also affect the moisture content of live fuels, particularly annual and perennial grasses and herbs (Pellizzaro et al. 2007). In periods of extended drought, the amount of fuel available to burn may increase due to plant mortality, or the drying out of fuels that would normally be moist during a normal fire season (e.g. rainforest). Extended drought may also result in high levels of landscape-scale dryness in which wet soaks and creeks dry out and no longer act to inhibit widespread fire propagation.

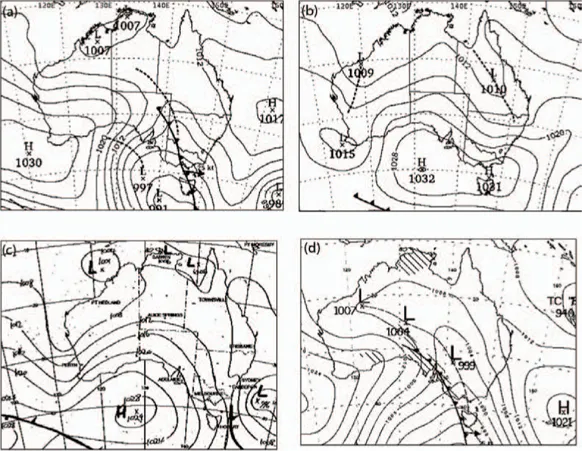

Synoptic weather patterns

Each climate region in Australia experiences distinctive synoptic weather patterns during the fire season. Synoptic patterns associated with severe fire weather are generally such that hot, dry air is drawn from the centre of the continent (Figure 3.3). Often the passage of a frontal trough across a region exacerbates fire weather conditions, resulting in extremely high temperatures and strong winds ahead of a cold front that, although associated with a very rapid drop in temperature and rise in humidity, also brings abrupt changes in wind direction that can turn flanks into head fires and complicate suppression efforts.

Diurnal patterns

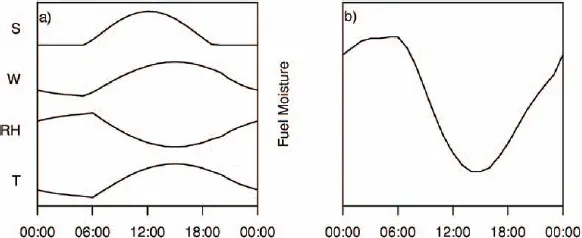

Within a given air mass, there is a regular diurnal cycle in the main variables that affect fire behaviour (Figure 3.4a). These cycles in solar radiation, temperature and humidity produce a diurnal cycle in the dead fine fuel moisture content that follows, but lags behind, relative humidity (Figure 3.4b). This, combined with the afternoon peak in wind speed, means that fire behaviour will typically peak during late afternoon and decline overnight to a minimum in the early morning.

Figure 3.3. Mean sea level pressure analysis of typical weather patterns associated with ‘bad’ fire weather conditions in various parts of the continent. (a) Eastern Australia 25 September 2009; (b) Northern Australia 26 October 2009; (c) Western Australia 31 December 1999; and (d) Southeastern Australia 30 January 2003. (Source: Bureau of Meteorology online Mean Sea-Level Pressure analysis archive, http://www.bom.gov.au/australia/charts/archive/index.shtml, used with permission)

Figure 3.4. (a) Typical diurnal change in solar radiation (S), wind speed (W), relative humidity (RH) and air temperature (T); (b) The result is a diurnal change in dead fine fuel moisture content.

Solar heating of the ground during the day means that the atmosphere is most unstable, and the potential for plume development and long distance spotting is greatest, during the afternoon. At night, the land surface re-radiates the heat absorbed during the day and slowly cools. Differences in the rate of heating and cooling of the land during the night and day can induce air flow up slopes (anabatic) and down slopes (katabatic) (see Sharples 2009). Differences in the heating of the land and ocean can result in the establishment of circulations, such as sea breezes, that have relatively consistent strength and direction in some regions (Schroeder and Buck 1970).

Atmospheric stability

The profile of temperature and humidity in the atmosphere governs the vertical motion of air and the formation of clouds. These affect the development of the convection column above a fire, modifying the wind in the vicinity of the fire and the fire behaviour itself, particularly spotting (Byram 1954).

Depending on the rate at which air temperature changes with height (known as the lapse rate), the atmosphere may be unstable or stable. Under unstable conditions (in which a rising parcel of heated air has the tendency to keep rising), fire behaviour is more likely to be erratic and unpredictable, and the convection column is more likely to reach a significant height and allow long distance spotting. Under stable conditions, fire behaviour is less likely to be erratic, with less vertical development in the convection column and shorter spotting distances. The Haines Index (Haines 1988) was developed in the US to link atmospheric stability and humidity with erratic fire behaviour, and has recently been extended to be more relevant to Australian conditions (Mills and McCaw 2010).

Wind

Wind is the most dynamic variable influencing bushfire behaviour. Wind is the result of the bulk motion of the atmospheric boundary layer over the landscape (Stull 1988). Interactions with the geostrophic flow above the boundary layer form eddies, which then cascade down through the boundary layer to the surface (Wyngaard 1990, Kaimal and Finnigan 1994). As a result, the speed and direction of the surface wind varies widely over short time periods as well as with location and height above the ground (Finnigan and Brunet 1995, Sullivan and Knight 2001).

A fire burning in light and variable winds will spread inconsistently in direction as it responds to gusts and lulls in the flow (Cheney et al. 1998). It is not until the wind speed has reached some minimum threshold value that a bushfire will spread in a consistent direction. This threshold depends upon the fuel in which the fire is burning (Burrows 1994).

Fuels

Fuel is a generic term used to describe combustible material. In the case of a bushfire, the fuel is the burnable live and dead vegetation that may be consumed in the passage of the fire. A bushfire is often described according to the predominant fuel type in wh...