![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

And God created great whales.

Genesis, chapter 1, verse 21, first quoted in Herman Melville’s

‘Extracts’ at the beginning of Moby-Dick, 1851.

The word ‘whale’ is usually taken to mean the larger members of the mammalian order Cetacea – the whales, dolphins and porpoises. That classification into the three groups is loosely based on size. The term ‘whale’ generally refers to cetaceans over about 10 metres long (although two of the smallest, the dwarf minke and pygmy right whales, grow only to about seven metres, while others, such as pilot whales and some beaked whales, can be even smaller); ‘dolphins’ are between about two and five metres long; and ‘porpoises’ below two metres. But there is no real biological basis for these different names.

Zoologically speaking the Cetacea are divided into two suborders, based on their feeding apparatus: the baleen whales, the Mysticeti, and the toothed whales, the Odontoceti. The baleen (or ‘moustached’) whales use baleen plates in the mouth to filter their food from sea water, while the toothed whales all possess teeth, even though in some species the teeth are extraordinarily modified and reduced in number. And while all the mysticetes are ‘whales’, only relatively few odontocetes are whales, such as the sperm and killer whales, the weirdly modified beaked whales, the solely arctic narwhal and white whale, the pilot whales, and one or two others. The rest of the odontocetes comprise the dolphins and porpoises.

Of the two suborders, the odontocetes are much more numerous, with eight families, 34 genera and some 73 species. There are only four families of mysticetes, comprising six genera and 14 species. By world standards, Australia’s cetacean fauna is moderately rich. It has representatives of eight of the world’s 12 families, 27 of the 40 genera, and 44 of the 87 or so species currently recognised.

Only one of our cetaceans is endemic – the recently described snubfin dolphin, Orcaella heinsohni, from Townsville, Queensland. However, Australia is the type locality for that and three other species – the pygmy right whale, Caperea marginata, first described from three baleen plates collected at the Swan River Colony, Western Australia; the southern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon planifrons, collected as a beach-worn skull from the Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia; and the tropical bottlenose whale, Indopacetus pacificus, described from a skull collected from the beach at Mackay, Queensland. Until recently the tropical bottlenose whale was quite unknown as a living animal.

Four of the world’s cetacean families are not found here. The absent ones are the northern hemisphere gray whales (family Eschrichtiidae, now found solely in the North Pacific); the Arctic narwhal and beluga (family Monodontidae); and two families of the largely freshwater river dolphins found in South America and eastern Asia. None of the porpoises are found regularly near the Australian continent. The single ‘Australian’ representative, the spectacled porpoise, Phocoena dioptrica, is an Antarctic animal that occasionally strays north into our waters. The remaining seven families are well-represented here. This is not surprising given Australia’s wide range of coastal habitats – southern cool temperate to northern tropical – and its position in the path of migration routes of such regular ocean travellers as the humpback and southern right whales.

Not unexpectedly, Australia shares many cetacean faunal elements with the two other southern continents and New Zealand. But it lacks one group: the coastal dolphins of the genus Cephalorhynchus (the South American Commerson’s and Chilean dolphins; Haviside’s dolphin of south-west Africa; and Hector’s dolphin of New Zealand).

Only three cetaceans have been sufficiently numerous close to the Australian coast to be commercially important here: the southern right whale, the humpback whale and the sperm whale. This contrasts with the situation off southern Africa, where eight species of whale (blue, fin, sei, Bryde’s, minke, humpback, southern right and sperm) have all been subjected to coastal whaling. Interestingly enough all these species, except for the tropical/temperate Bryde’s whale, have also been subjected to whaling in the Antarctic, well south of Australia.

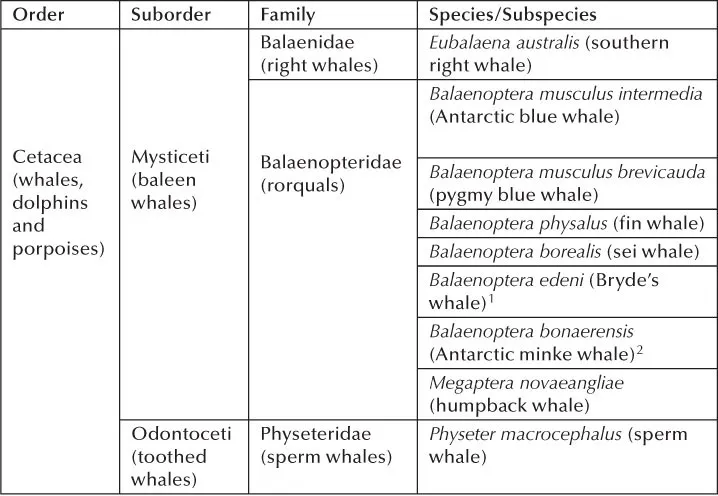

Table 1.1: Great whale species dealt with in this book

1 See ′Chapter 5, Bryde’s whale′ for current status of Balaenoptera omurai

2 See ′Chapter 5, Minke whale′ for current status of the ′dwarf′ minke

That brings us to the ‘great whales’, the subject of this book (see Table 1.1). Here too we are not talking zoologically, but the reference is to the larger whales, almost all once commercially important, and several still highly significant in the context of the Australian fauna. Strictly speaking the ‘great whales’ comprise the six baleen whales (blue, fin, sei, Bryde’s, humpback, southern right) and the one toothed whale, the sperm whale. But I have added another – the minke – not quite a ‘great whale’ in the traditional sense, but important enough in the Australian context to be included here. Not only does it have two forms – the dwarf minke, subject of a popular commercial ‘swim’ program off northern Queensland, and the Antarctic minke, common in summer in the Antarctic – but the latter is frequently in the news because it has been, and continues to be the main (and controversial) target of ‘scientific permit whaling’ in the Antarctic south of Australia. So minkes, of both forms, are included here.

Some explanation is necessary here about the terms ‘baleen whale’, ‘balaenopterid’, and ‘rorqual’. The ‘baleen whales’ are all those species that make up the suborder Mysticeti. The ‘balaenopterids’ are all the members of the family Balaenopteridae, including the six members of the genus Balaenoptera (blue, fin, sei, Bryde’s and the dwarf and Antarctic minke whales) and the single member of the genus Megaptera (the humpback). Those seven species (assuming the dwarf minke to be separate) are the ‘rorquals’. Professor Lars Walløe of the University of Norway has shown that the word rorqual comes from the Norse rørkval, from an earlier word reydr meaning ‘tubes or grooves’, referring to the ventral grooves of Balaenopterids. The word rørkval became rorqual first in French, then English. Strictly speaking ‘rorqual’ probably should not include Megaptera, the humpback, but for present purposes, it will be taken to mean any of the species in the family Balaenopteridae, which includes the humpback. Right whales, as members of the separate family Balaenidae, are not rorquals, and do not have ventral grooves.

And why just Australia’s ‘great whales’? First, because they make a sufficiently coherent and convenient grouping for treatment together, and second, because many of these elusive and graceful creatures have been, or are, specially important to Australians.

For the early settlers, whales were a major feature of the landscape – right whales in the Derwent River, Hobart, for example. In the early days, right whales and sperm whales were taken by visiting Yankees, British or French, as well as by the colonials. In more recent times, humpbacks were the target of the whaling industry based at coastal stations in Western Australia, Queensland and New South Wales, just after World War II, while illegal Soviet operations in the 1960s took humpbacks, sperm and pygmy blues. These days, the highly popular whalewatching industry is based around humpbacks, right whales, blues, and dwarf minkes.

Most particularly, whales are worth writing about not just because the blue whale is the largest animal that has ever lived, or the sperm whale is the biggest and possibly most bizarre of the toothed whales, but because they include the humpback and southern right whales, both of which have for some years been coming back from the brink. As the largest and most iconic visitors to Australian shores the great whales deserve our admiration, respect, and continued care. It is my hope that the information gathered in this book will help achieve those aspirations.

![]()

2

FASCINATING CREATURES

So is this great and wide sea, wherein are things creeping innumerable, both small and great beasts. There go the ships: there is that leviathan, whom thou hast made to play therein.

Psalms 104: 25, 26; quoted by L Harrison Matthews in

The Whale, 1968.

Since the earliest days of natural history … the … whale has been subjected to constant misrepresentation … [as a result] of that heated imagination which leads some enthusiasts to see nothing in nature but miracles and monsters.

Baron Georges Cuvier, quoted by Thomas Beale in The Natural

History of the Sperm Whale, 1839.

Few people nowadays would have much difficulty telling you that a whale, though it lives in the sea, is not a fish but a mammal, like its smaller relatives the dolphins and porpoises. Nor that Australia once used to kill whales commercially – but of course that was a while ago. Nor that now you can see whales in spectacular David Attenborough documentaries, or on the Discovery Channel, and that you can go whalewatching and experience them as real live animals, out there at sea, amazing, friendly, inquisitive creatures … literally in their element.

It wasn’t always quite like that. Aristotle knew they were mammals – they had lungs, dolphins snored (through a blowhole), whales and dolphins gave birth to live young and fed their young on milk. But despite Aristotle’s wisdom, most ancients thought whales were mythical creatures, literally monsters of the deep. Jonah was swallowed by ‘a great fish’ – in those days equivalent to a whale. Leviathan (though originally probably a crocodile) was any absolutely enormous creature, so whales were leviathans.

In mediaeval times, the Scandinavians and Icelanders wrote a lot about whales – a thirteenth century volume even says there’s not much more than whales worth writing about (at any rate in Norway). Some whales were kind and helpful – minke whales used to help fishermen by driving fish shoals inshore, and fin whales were good to eat. A mediaeval Norwegian document (translated by Prof. Lars Walløe of the University of Oslo) states that the sperm of a whale ‘if you be sure that it came from this sort and no other … will be found a most effective remedy for eye troubles, leprosy, ague, headache and … every other ill that afflicts mankind’. Other whales, though, were monsters, and dangerous. And because artists had often never actually seen a whale, their illustrations tried to make them look as fearful as possible.

Occasionally a whale would strand on the shore, and cause great interest. It has been said that old engravings often exaggerate the size of such creatures by drawing the people around it as dwarfs, so the animal seems even more monstrous than it really is. Even now, as Leonard Harrison Matthews says in his book The Whale, old beliefs about whales die hard. Terms such as whalebone (not bone at all), ambergris (certainly not amber) and spermaceti (nothing whatever to do with reproduction), are still in common use.

Whales are still seen as mysterious, fascinating creatures. Despite modern technology, they inhabit a world still largely unexplored and unknown. They can only be seen, or rather glimpsed, when they are near the sea surface, either from boats, or perhaps from shore, or underwater by divers or from submersibles. They include, in the blue whale, the largest animal ever to have lived on the planet. That huge animal can grow to 30 metres in length – that’s equivalent to the height of a six storey building. A blue whale can weigh more than 130 tonnes – more than the weight of 20 African elephants. Even the largest dinosaurs may have weighed not quite 100 tonnes. And yet, despite its vast size, the blue whale feeds on individual creatures only a few centimetres long, although it does take in a huge quantity of them at a time, perhaps more than four tonnes a day.

Superbly and wonderfully specialised, whales – as well as the dolphins and porpoises – spend their entire lives in water. Among the marine mammals, only the dugong is so independent of land. Seals, sea lions, walruses, sea otters (usually) all need to come on to land at some time in their lives, mainly to reproduce.

That life spent entirely in water has so shaped their lives and so altered their bodies that cetaceans seem not to be mammals at all. They have had to overcome the physical resistance of water – hence streamlining, and loss of hair, and smoothness of skin. Water also conducts heat, so they have to insulate themselves. Water also conducts sound very well, and they have very special adaptations to take advantage of that.

As good mammals, whales, dolphins and porpoises all need to take in air at the surface, and to do that they have developed the ability to empty the lungs very rapidly through their blowhole. A large whale can exhale rapidly, taking only one to two seconds, and this is followed by an equally rapid intake of air. Once often known as the ‘spout’ and now more commonly (and accurately) as the ‘blow’, the blow may be the first, and sometimes only, visible evidence of a whale’s presence at sea. Blue whales have a tall and columnar blow; humpbacks have a ‘bushy’ blow; the blow of sperm whales is short and directed diagonally forwards while that of right whales is V-shaped. The blow’s visibility may to some extent be due to a small amount of water carried up from the blowhole, but is more generally believed to be due to the cooling effect of air released under great pressure. Even in the tropics, the cooling effect causes condensation of water vapour and the ‘spouting’ appearance.

Among the cetaceans, two rather different life styles have evolved within the two distinct suborders: the mysticetes – whalebone or baleen whales; and the odontocetes – toothed whales, dolphins and porpoises. The relatively few baleen whale species contrast markedly with the much more numerous odontocetes. Most of the mysticetes are very much larger in size. Only one odontocete, the sperm whale, at a maximum length of around 18 metres (and then only in the largest males) even approaches the larger baleen whales. The next biggest odontocetes – killer whales and some beaked whales – are full grown at around nine metres and only exceed the size of the very smallest baleen whales.

In other ways, too, the baleen and toothed whales are very different from each other. For one thing, baleen whales are grazers, taking in vast quantities of their food at a gulp, while toothed whales actively c...