![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

“For, whoever will follow its pages, crayfish in hand, and will try to verify for himself the statements which it contains, will find himself brought face to face with all the great zoological questions which excite so lively an interest at the present day …”

(T. H. Huxley, 1880)

Charles Darwin’s friend and advocate, Thomas Huxley, wrote a book about the crayfish in 1880 that he hoped would stimulate an interest in the zoological questions that were important then. Many of ‘the great zoological questions’ to which he referred remain unanswered 124 years later. This guidebook is a list of the players acting out these questions. Crab, shrimp, prawn, lobster, crayfish, yabby and bug are just some of the names used in Australian English to describe members of the Crustacea. To these can be added more culinary terms from other languages – langoustine, scampi and udang. Most Australians would recognise a crustacean on the sea shore or on the dining table. This book sets out to document the diversity of some crustaceans found along the southern coast of Australia and to provide a means to tell one from another.

Crustaceans are a group of related animals, meaning they probably had a common ancestor some time in the past. The features that they share are described in this introductory chapter. This volume deals with only some crustaceans, mainly those called ‘decapods’ and only those found in southern Australia. There are reasons for having such a narrow scope – the main one being that one volume can cope with no more. Much has been written about crustaceans before and in Chapter 1 this is reviewed to place present-day knowledge in context. In this introduction, some crustaceans of special interest for one reason or another are discussed. This introductory chapter explains how the book has been planned and what to expect from each section.

Chapter 2 deals with the higher systematics of Crustacea and explains how the Decapoda and Stomatopoda, the only groups dealt with, are related to the many other crustaceans. General morphology is dealt with and specialist terms introduced. Having communicable names for species is essential and the principles that govern these are briefly explained.

Chapters 3 to 12 cover crustacean groups in turn. Chapter 3 deals with prawns and related animals, Chapter 4 with most shrimps, Chapter 5 with coral shrimps, Chapter 6 with deep-sea lobsters, Chapter 7 with crayfish and scampi, Chapter 8 with sponge shrimps and ghost shrimps, Chapter 9 with rock lobsters and bugs, Chapter 10 with hermit crabs and squat lobsters, Chapter 11 with crabs, and Chapter 12 with mantis shrimps. The last was written by Shane Ahyong. There follows a glossary, because we have no choice but to learn a new language to identify these animals, with diagrams to explain the special terms applicable to different groups of decapods.

What is a crustacean?

Insects, spiders, scorpions and millipedes are just some of the Phylum Arthropoda, that large group of animals distinguished from all others by their hard skin, or exoskeleton, and a segmented body. Crustaceans belong to this phylum too and may be called the insects of the sea. While insects are diverse and common on land, crustaceans are diverse and common in the sea. Unlike insects, which are more or less excluded from marine environments, crustaceans do get on to land and into fresh water. Crustaceans, then, are arthropods that usually have many pairs of legs, a pair per body segment, and above all have two pairs of antennae (special sensory legs), one pair on each of the first two segments of the head. Insects, in contrast, have relatively few pairs of legs and only one pair of antennae. Chapter 2 goes into more detail about the classification of crustaceans.

These details are of little importance when it comes to recognising a crustacean. We know from childhood what is a crab, shrimp or lobster and have never counted legs or antennae. In a catch of animals from a marine habitat it is simple to separate crustaceans from fish, snails, worms and seastars. Crustaceans are obvious to the marine biologist in the way that ants and flies are to land-lubbers for the simple reason that they are so abundant and so diverse. Densities may be in thousands of individuals per square metre of sea floor or cubic metre of ocean water and commonly many different kinds live side by side. The number of species in the world for which we have names is more than 50 000 but this is just a small fraction of the true number, which could be a million for all the world’s oceans. Or perhaps ten million. The reason for this underestimate is that only a small percentage has been described and are known by formal names. (Luckily for us this is not the case for the species in this book.) But for crustaceans as a whole, especially in Australia and especially for lesser known groups, this is true. Of all the c. 650 species of Crustacea in Port Phillip Bay, a well-studied bay near Melbourne, only about 13% are named. For the Order Isopoda, a group of small relatives of slaters, in deep marine seas off eastern Australia, only 10% of 359 species discovered have names (Poore et al., 1994). An area of half a metre-square of sand at the bottom of Port Phillip Bay may be home to as many as 70 species of crustaceans; most of these are undescribed.

The significance of crustaceans in the world’s ecology can not be ignored. Crustaceans range in size from one-tenth of a millimetre maximum diameter (a tantulocarid parasite) to four metres across (a Japanese king crab). The mass of Antarctic krill in the oceans may be greater than that of any other single species. One species of oceanic copepod may be the most common animal on earth. And crustaceans have been found almost as far back in the fossil record as any group of complex animals. This contribution deals with but a few species from a small area.

Scope of this work

This guide to species identification deals with just decapods and stomatopods. This is simply because these are the only major groups which can be reliably identified to species in southern Australia. While peracarid crustaceans such as amphipods (Lowry & Stoddart, 2003) and isopods (Poore, 2002) and copepods may be more common, very few are named.

The Decapoda are just one Order of the Superorder Eucarida in the Subclass Eumalacostraca of the Class Malacostraca of the Subphylum Crustacea of the Phylum Arthropoda. The Stomatopoda are more primitive crustaceans in the generally-accepted ranking of the subphylum. They too comprise an Order but in another Subclass, Hoplocarida, of the Malacostraca. The morphological differences between stomatopods and decapods are profound. Both are included in this guidebook because individuals are much larger than typical examples of all other groups. Chapter 2 has more on crustacean taxonomy and the features that distinguish these taxa.

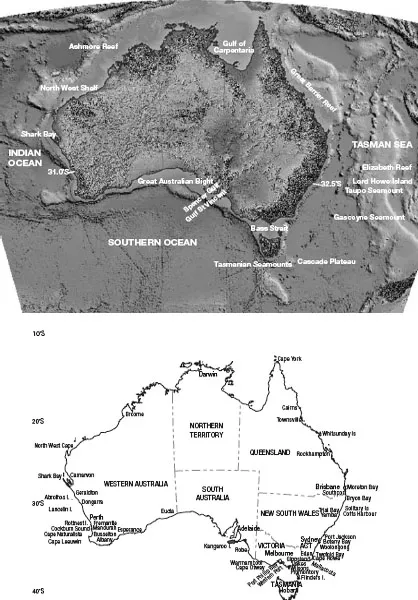

This book confines itself to southern Australia for an equally practical reason. The marine fauna of southern Australia has a significant endemic component, meaning many of its species do not occur elsewhere. In contrast, the fauna of northern Australia is part of a much larger fauna extending from Japan through the western Pacific Ocean into the Indian Ocean, the so-called Indo-West Pacific fauna. The reasons for this dichotomy are explained in the Environment, Ecology and Biogeography section. Our task is made easier by restricting the coverage to a fauna that is smaller and taxonomically less confused. Even so, many Indo-West Pacific and northern Australian species reach as far south as ‘southern Australia’. Northern limits to this study are set at 32.5°S on the east coast and 31°S on the west coast to include the cities of Sydney and Perth (Fig. 1). All estuarine and marine environments are covered, from the intertidal down through the subtidal, across the continental shelf, down the continental slope to the deep sea. Most decapods live on the sea floor but also included are species that swim, especially mesopelagic oceanic species. Species known from seamounts off south-eastern Australia are included (Fig. 1, Pl. 1a).

Fig. 1. Top: geophysical and bathymetric map of Australia and surrounding continental shelf and seas. Major oceanographic features referred to in the text are indicated. The northern limits of the region covered, 32.5°S on the east coast and 31°S on the west coast, are marked. Bottom: political map of Australia with place names mentioned in text. States are abbreviated throughout as follows – Northern Territory (NT), Queensland (Qld), New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (Vic.), Tasmania (Tas.), South Australia (SA), Western Australia (WA).

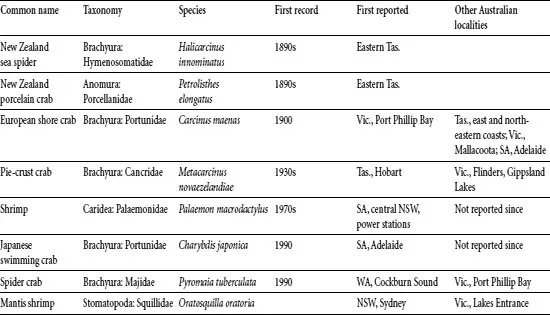

Table 1. Species of decapod and stomatopod Crustacea introduced to Australia

Within these geographic and environmental ranges some places, like shallow environments near population centres, are better explored than others and the chances of discovering new species are low. It would be no surprise, however, to find new records or even new species on the shelf of the Great Australian Bight, or on the continental slope or seamounts. Some species appear in the keys here on the basis of just one or two records. These may be genuinely rare but others are occasional vagrants from warmer waters. The fauna of Rottnest Island off Perth includes several species at the southern end of their range. There is evidence for warming of waters along the south-eastern coast during the 1990s and more subtropical species may turn up in future.

This is principally a guidebook for identification but ecological observations are referred too in the few cases where they have been made.

Davie’s (2002a, b) catalogues were published while this work was in progress and provided a valuable source of information. The few discrepancies between his lists and the coverage here are explained by newly identified material in museums not seen by him and not published. Very few new taxonomic decisions have been made in this work.

Crustaceans of special interest

The crustaceans covered in this text are principally those met with on the shore or deeper marine environments of southern Australia. Of these, six crabs, one shrimp and one mantis shrimp are not native inhabitants and appear along with their 800 relatives in appropriate chapters (see Table 1). Decapods have been introduced to other parts of the world from their native areas by shipping and might be expected to eventually arrive, unwanted in Australia. Port Phillip Bay has a notorious reputation as a bay with a high percentage of exotic species (Hewitt et al., 1999, 2004) and species such as two shore crabs, Hemigrapsus pencillatus and H. sanguineus, and the Chinese mitten crab, Eriochier sinensis, now found in North America and Europe, might arrive unwanted. Just in case, these species are noted. If you find one, alert the local museum or fisheries authority!

Edible decapods are another group of special interest, most not native to southern coasts. Keys are given to Australian species of prawns, lobsters and crabs found for sale in southern cities.

History and resources

Like any group of animals, crustaceans have long attracted the attention of biologists and artists. Beautiful images of lobsters and crabs can be found in mosaics of ancient Roman cities, eighteenth century European still life painting and in the paintings of Australian Aborigines. The interest of these artists was surely because crustaceans are edible. Linnaeus included crustaceans in his Systema Naturae (1758), mostly in the genus Cancer. Many of the great European biological exploring expeditions of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries collected marine and freshwater crustaceans along with other exotic wildlife. Australia attracted considerable attention from early European biological collectors, but plants and terrestrial mammals and birds fascinated James Cook, Joseph Banks, Matthew Flinders, Robert Brown and Ferdinand Bauer more than did marine crustaceans. French scientists first sailed and sampled in Australia in 1788, the year that Port Jackson was established as a convict settlement. But it was the expedition sent by Napoléon Bonaparte aboard the Le Géographe and Le Naturaliste, under the command of Nicholas Baudin, that showed the first real interest in southern Australian crustaceans. The voyage arrived in the region in 1801 with the naturalist François Peron. The collections that were taken back to the Jardin des Plantes, the natural history museum in Par...