![]() Part I

Part I![]()

Classification

An important foundation stone of human thinking is the urge to sort things. Every time when we come face to face with something unfamiliar, we try to fit it into some kind of a system in order to understand what it is.

Scientific classification (the science of taxonomy or biological systematics) is a method by which biologists group and categorise extinct and living organisms. Modern classification is based on the system of Carolus Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish scientist.

This system has been revised several times in order to accommodate the results of new research, especially the Darwinian principle of evolution and more recently genomic analysis through DNA sequencing.

A perfect system of classification has yet to be developed. What we have – the modern version of the Linnaean system – needs constant honing and this is what taxonomists do all around the world.

The ingenuity of the Linnaean system is manifested by its flexibility and by its ability to accept changes without getting destroyed in the process. Ever since its birth, many new species are being added in the world taxonomic ‘inventory’ each year. Now more than 1.5 million species of organisms bear names, given to them according to the Linnaean system.

Apart from the fact that the Linnaean system of classification is capable of accommodating an endless deluge of new species, it has another great feature – binominal nomenclature.

Linnaeus insisted that every species shall have a Latin name, consisting of two words. This method of creating names in this way is known as binomial nomenclature.

The Linnaean binomial nomenclature is simple and practical. Every species has a ‘surname’, known as generic name, which signifies that it belongs to a particular group known as a genus (plural: genera), and a ‘given name’, known as the specific name, which denotes its identity as a species. The combination of these two names is the scientific name of a species. There could be many species within one genus and in that case they all shall have the same generic name, but their specific names must all be different. No two or more species of any organism should have the same generic and specific name in one combination. However, a specific name can be given to more than one species, providing they all belong to different genera.

A scientific name in reality consists of more than two words. It is customary to give the generic and specific names first, followed by the name of the person, known as the author, who described and named the species. After that, a four-digit number may be placed, indicating the year when the name was created. For instance Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 means that the species cervus belongs to the genus Lucanus, and it was named by Linnaeus in 1758. When the author’s name is in parenthesis: Geotrupes stercorarius (Linnaeus, 1758), it means that the species was initially named by him but later on it was transferred from its original genus to another. Linnaeus initially described and named this species as Scarabaeus stercorarius, but later on, when the genus Geotrupes was erected, stercorarius was transferred to it.

When a species is renamed, the old name becomes a synonym. In scientific works, these synonyms are usually mentioned in addition to the valid names in order to avoid confusion.

Traditionally, generic and specific names are printed in italics and in handwriting or, if written by a typewriter, without italicised letters and underlined.

Since the mid-1980s DNA analysis became more and more important in identifying species in entomology. The process is quite complex, relatively expensive and slow if compared with the traditional entomological process for determining species by their morphological characteristics.

At present, DNA analysis is not within the reach of most amateurs and only a certain percentage of professional researchers have frequent access to genome-investigating methods and equipment. But it is more than likely that in time techniques will improve and become more accessible to a greater number of entomologists. If this becomes a reality, taxonomy will undergo tremendous changes, many species will be reassigned, higher taxa will be revised and the current face of entomology will change forever.

![]()

The language of entomology

Ancient Greek and especially Latin used to be the languages of science in Europe. The teachings of the earliest Greek and Roman scientists were respected and accepted throughout millennia. Time, however, didn’t stop and the world kept changing; the ancient Greeks and Romans vanished and their languages would have died with them, if scientists and the practitioners of Christian religions didn’t use them. Why did they keep using these ‘dead’ languages? A ‘dead’ language is not subject to changes, so a script made in Latin or Ancient Greek means the same today as the day it was written – even if it was 2000 years ago. This would be impossible to achieve using a ‘living’ language, which could change within a relatively short time, so much so that it would become unintelligible or, at best, difficult to understand precisely. More than likely, this was the main reason why early naturalists, such as Linnaeus, chose classical Latin to describe and name newly discovered species of plants and animals.

As methods of research advanced, more and more detailed and precise descriptions were required. Pure Latin, being a ‘dead’ language, soon became inadequate for the task. It became very difficult to speak and write Latin fluently in a continuous and expressive manner, and more and more frequently scientists resorted to the most widely used spoken and written European languages. By the 19th century German, French and English became the languages of scientific publications aimed at international audiences. However, Latin and Greek words were used when these languages couldn’t describe particular features or habits of an organism in a concise and precise manner. By using the grammar and vocabulary of a ‘live’ language but adding as many Latin and Greek words as necessary, a scientific language developed. Workers of many nationalities followed this method to create their own versions of a scientific language, based on their mother tongues. Difficulties in communication between the scientific communities of various nations led to the realisation that one language should eventually dominate science worldwide. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the English language became the dominant international language. It is not only customary but also practical to publish scientific works in this language, as it is now widely understood all over the world. Publishers and authors often find it necessary to include English summaries of their non-English-language publications.

When an organism and its features are described in a scientific manner, the description must be as accurate as possible. The best way to do this is to avoid expressions that could be perceived differently by various readers and instead use accurate, purposeful words in order to convey a concise description. No living language has a vocabulary that would be suitable for this job without blending some Latin and/or Ancient Greek into it.

![]()

Morphology

The scarab-like beetles:

Scarabaeoidea

The stag beetles, the Lucanidae, are a family within the superfamily Scarabaeoidea. Members of this superfamily generally have lamellate antennae. The terminal segments of this highly developed organ form a club, composed of plates known as lamellae. The typical scarab lamellae can be compressed into a ball or spread out in a fan-like manner. In the Lucanidae the antennal club is quite variable and is in some species flabellate rather than lamellate.

The main morphological characters of the Australian Lucanidae

Body elongate, some robust, 5–72 mm

Head prognathous, males often with prominent mandibles, some branched

Antennae with long scape, often geniculate, three to seven loose segmented club that cannot be completely closed

Eyes entire or with a partial or complete canthus

Labrum and clypeus usually fused to frons

Scutellum visible

Abdomen with five visible ventrites

Legs relatively long and slender, protibia well developed

Tarsal formula 5–5–5

Usually brown or black, some species have lighter dorsal patterns, some vividly metallic.

An important character that is used to differentiate lucanids from other scarabs is the number of segments in the club. In the Australian Lucanidae the antennal club is composed of three to seven segments and the antennae have 10 segments in total. The antennae vary from being geniculate (elbowed) to non-geniculate and have a relatively long scape (first segment of the antenna). The genus Lissapterus has at the most only a slightly pectinate antennal club whereas in the genus Ceratognathus the comb-like segments are quite long (especially in males) and movable, but cannot be closed fully into a compact club.

A very conspicuous character of these beetles is their sexual dimorphism. Males of many species have large, ornate mandibles, while females have smaller and very simple ones. The mandibles of male Lucanidae are often used in combat with rival males, especially when attempting to mate with a nearby female or in self-defence against would-be predators. Usually it is quite easy to distinguish the sexes through their mandibles, although in some cases the smallest males look very much like females and several species show only minimal sexual dimorphism. The sexes are indistinguishable externally in some genera (e.g. Figulus).

Another well-known character in this family is the allometric development of the male mandible (the size of the mandible is proportional to the size of the body), which has often confounded taxonomists. The marked differences in the teeth of the mandibles may depend on the overall body size of the male. In this book, where this occurs, we will simply refer to small males of a species as ‘minor males’ and large males as ‘major males’.

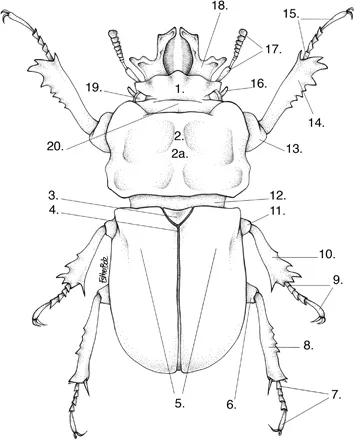

Schematic map of a non-specific stag beetle (based on Ryssonotus nebulosus), dorsal view. 1. Frons, 2. Pronotum, 2a. Disc, 3. Scutellum, 4. Suture, 5. Elytra, 6. Hind-or metafemur, 7. Hind- or metatarsus, 8. Hind- or metatibia, 9. Mesotarsus, 10. Mesotibia, 11. Mesofemur, 12. Mesothorax, 13. Fore- or profemur, 14. Fore- or protibia, 15. Fore- or protarsus, 16. Maxillary palp, 17. Antenna, 18. Mandible, 19. Eye, 20. Vertex. Drawing: Esther Bolz.

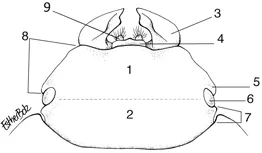

Schematic map of the head of a non-specific stag beetle (based on Lucaninae female), dorsal view. 1. Frons, 2. Vertex, 3. Mandible, 4. Labrum, 5. Canthus, 6. Eye, 7. Postocular margin, 8. Preocular margin, 9. Galea (outer lobe of the maxilla). Drawing: Esther Bolz, after Holloway.

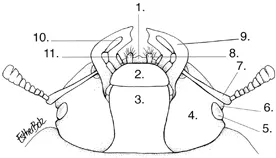

Schematic map of the head of a non-specific stag beetle (based on Lucaninae female), ventral view. 1. Labrum, 2. Mentum, 3. Gula (throat), 4. Gena (cheek), 5. Eye, 6. Canthus, 7. Antenna, 8. Galea (outer lobe of the maxilla), 9. Mandible, 10. Maxillary palp, 11. Labial palp. Drawing: Esther Bolz after Holloway.

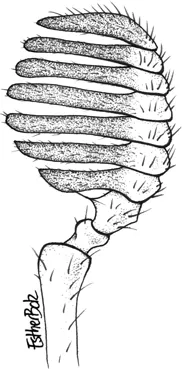

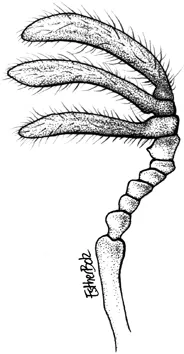

Antenna of Syndesus cornutus. Drawing: Esther Bolz.

Antenna of a male Ceratognathus sp. Drawing: Esther Bolz.

Antenna of a Lamprima sp. Drawing: Esther Bolz.

Australian lucanids are mostly black, dark brown or, in the case of the subfamily Lampriminae, a vivid colour with a metallic lustre. The scutellum is always visible, although sometimes it may be rather small.

![]()

The Lucanidae

Stag beetles have always interested coleopterists, amateurs and professionals alike. Many of these beetles have spectacular shapes, their larvae lead cryptic lives and, in most species, people do not commonl...