![]()

SECTION 1.

SCENE SETTING

![]()

1

Linking Australia’s landscapes: an introduction

James Fitzsimons, Ian Pulsford and Geoff Wescott

Australia has undergone a recent surge in interest in creating networks and initiatives that aim to ‘link up’ habitats and landscapes that have been fragmented by clearing or varying land uses or ownership. This increased interest has been stimulated by the involvement of a range of players – government, non-government organisations, landowners and the broader community.

In Australia, these initiatives include a range of activities that are promoted under a variety of names including ‘biosphere reserves’, ‘wildlife corridors’, ‘conservation management networks’, and ‘biolinks’, among others. These various initiatives are not just about achieving ‘connectivity conservation’ but are often couched in terms of ‘landscape-scale’ projects. There has been relatively little analysis of these diverse and practical initiatives in a single synthesis. Nor have the perspectives of those who have established or are coordinating and managing these projects received as much attention as they deserve. The result has been a gap in dialogue and understanding between the theoretical discussions of developing ‘a network of corridors’ across a continent (or state jurisdiction) and the practical reality of establishing and operating such initiatives in the landscape.

We aim in part to address these gaps through this book by bringing together the lessons from a diverse range of established connectivity initiatives and policy frameworks, together with a series of broader themed chapters encompassing aspects such as social, ecological and governance considerations. Initiatives featured include those from all Australian states and territories, and many initiatives which cross state and territory boundaries. The chapter authors are from universities, non-government organisations, state and national government agencies, research institutions and consultancies. Our intention, and hope, is that the descriptions in this book will not only inform policy makers, land managers, facilitators, and scientists, but it will also stimulate even greater efforts ‘on the ground’ by being of interest to the general public as well.

This book set out with the aim of canvassing a broad range of these multi-tenure conservation initiatives, described by the people directly involved in each project, not only to document the successes and challenges of these initiatives at specific geographies but also to begin to analyse if there were critical common lessons that have been learnt already in this new and evolving field. In particular we were keen to see if there were emerging models of approach that could potentially be adapted by new entrants into connectivity conservation initiatives, rather than have such groups repeat the mistakes of others.

In choosing a cross-section of examples of various approaches, we have focused on those with several years of experience behind them. We recognise there are other initiatives out there and many more emerging or proposed as this book goes to press (see Whitten et al. 2011 and NWCPAG 2012 for example). There have been of course several significant books already written on connectivity conservation both internationally (e.g. Soulé and Terborgh 1999; Crooks and Sanjayan 2006; Worboys et al. 2010; Hilty et al. 2012) and for Australia (e.g. Saunders et al. 1996; Bennett 2003; Lindenmayer and Fisher 2006). This book aims to be different in focus concentrating on the practical on-ground attempts at landscape-scale conservation.

We were concerned that there was some danger there would be significant repetition in the case studies but this has proved not to be the case. While there were several common themes, outlined in the synthesis at the end of this book, there were also many differences in approach.

During the course of preparing this book, policy on the creation of a National Wildlife Corridors Plan was released by the Australian Government (DSEWPC 2012a). The plan was broad in nature and the draft of the plan (NWCPAG 2012) met with a mixed response from public submissions (DSEWPC 2012b). Many were keen to see the concept on the national agenda and for potential federal financial support, but others were worried about the potential of the lessening of the role of the National Reserve System, proposed new legislation and the proposed process for nomination of National Wildlife Corridors. The authors of various chapters in this book reflect some of this diversity of views.

Before outlining the chapters that follow we would like to make it clear that the focus of this book is not a review of the ecological theory behind connectivity conservation, or related terms such as corridors (although some chapters do address this). It is a book about real, on-ground examples of trying to achieve multi-tenure conservation at scales from landscape to sub-continental by many different, and committed, departments, organisations, individuals and communities.

The book is divided into four main sections with a fifth acting as summary.

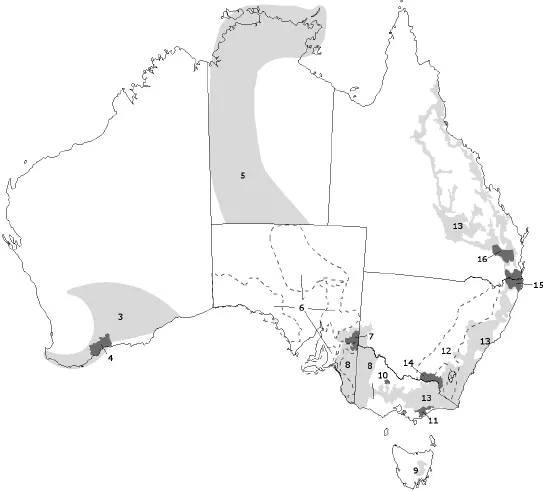

Section 1 provides an overview and international perspective on the state of connectivity conservation efforts as an introduction and background to Section 2, where the history, successes, lessons and application of those lessons for 14 case studies from around Australia are described by the practitioners of connectivity conservation. We have taken a ‘geographic’ approach to ordering the case study chapters, moving from west to east (Figure 1.1).

Section 3 outlines six policies and frameworks from different parts of Australia and New Zealand. These chapters consider approaches beyond the individual initiative; in effect efforts to create or coordinate ‘networks of networks’ or ‘systems of corridors’.

Section 4 explores broader themes associated with multi-tenure connectivity approaches, namely connectivity conservation principles, social dynamics, governance arrangements, socio-economic considerations and the importance of interdisciplinary research.

Section 5 synthesises the key themes raised by the authors throughout the book and suggests areas for further research.

Figure 1.1 Case study conservation networks featured in Section Two of this book. Differences in shading differentiates overlapping networks. Numbers refer to chapter numbers: 3 – Gondwana Link, 4 – Fitzgerald Biosphere Reserve, 5 – Territory Eco-link, 6 – South Australian NatureLinks, 7 – Riverland (Bookmark) Biosphere Reserve, 8 – Habitat 141°, 9 – Tasmanian Midlandscapes, 10 – Wedderburn Conservation Management Network, 11 – Gippsland Plains Conservation Management Network, 12 – Grassy Box Woodlands Conservation Management Network, 13 – Great Eastern Ranges Initiative, 14 – Slopes to Summit, 15 – Border Ranges Alliance, 16 – Bunya Biolink.

References

Bennett A (2003). Linkages in the Landscape. The Role of Corridors and Connectivity in Wildlife Conservation. IUCN, Gland and Cambridge.

Crooks KR and Sanjayan M (Eds) (2006). Connectivity Conservation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

DSEWPC (2012a). National Wildlife Corridors Plan: A Framework for Landscape-scale Conservation. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Canberra.

DSEWPC (2012b). Draft National Wildlife Corridors Plan – public comment. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Canberra. Available: http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/wildlife-corridors/consultation/index.html [Accessed 9 September 2012].

Hilty JA, Chester C, and Cross M (2012). Climate and Conservation: Landscape and Seascape Science Planning and Action. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Lindenmayer DB and Fisher J (2006). Habitat Fragmentation and Landscape Change: An Ecological and Conservation Synthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood.

NWCPAG [National Wildlife Corridors Plan Advisory Group] (2012). Draft National Wildlife Corridors Plan. National Wildlife Corridors Plan Advisory Group, Canberra.

Saunders DA, Craig JL, and Mattiske EM (Eds) (1996). Nature Conservation 4: The Role of Networks. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping Norton.

Soulé ME and Terborgh J (Eds) (1999). Continental Conservation: Scientific Foundations of Regional Reserve Networks. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Whitten SM, Freudenberger D, Wyborn C, Doerr V, and Doerr E (2011). ‘A compendium of existing and planned Australian wildlife corridor projects and initiatives, and case study analysis of operational experience’. Report to the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. CSIRO, Canberra.

Worboys GL, Francis W, and Lockwood M (Eds) (2010). Connectivity Conservation Management: A Global Guide. Earthscan, London.

![]()

2

Connectivity conservation initiatives: a national and international perspective

Graeme L. Worboys and Brendan Mackey

Connectivity conservation

There has been a social and political revolution in the care and management of Australia’s landscapes in the 21st century. As the 19th and 20th century cultural imperative for clearing and converting the Australian bush has diminished, a new urgency for the conservation of bush and wildlife has emerged across Australia’s landscapes. This is manifesting among a growing and diversifying community of conservation practitioners as a commitment to protecting and restoring Australia’s native biodiversity and achieving more ecologically sustainable land management. This is especially so through the establishment of many strategically and grassroots-organised large conservation corridors. Corridor initiatives that have commenced include Gondwana Link in Western Australia, the Trans-Australia Eco-Link of South Australia and the Northern Territory, South Australia’s NatureLinks, Habitat 141° in Victoria–South Australia–New South Wales, the Great Eastern Ranges Corridor in Australia’s eastern states and the Midlandscapes initiative of Tasmania (see Chapters 3, 5, 6, 8, 13 and 9). This pioneering connectivity conservation work has witnessed the involvement of individual corridor champions, landowners, community groups, business groups, non-government organisations (NGOs) and some governments in hitherto unseen partnerships and collaboration. Connectivity conservation and the establishment of large corridors have captured the imagination and commitment of many Australians. They have become important to many people in providing a focus for community engagement around a shared conservation vision for the land they own, lease or are involved in managing.

Corridors help conserve natural areas across private, leasehold, public and Indigenous land tenures, and across land uses, including land worked for pastoralism, forestry, cropping, mining, water supply and defence. They are not protected areas in their own right but ideally embed and (where appropriate) connect protected areas. They are a voluntary use of land that for its success requires the involvement of many sectors of society and multiple individual contributions. Private landowners, lessees, government agencies and Traditional Owners, all have vital roles to play in contributing to conservation goals including maintaining and restoring structural and functional connectivity. Corridors can help maintain and enhance the natural integrity of protected areas by enabling key processes to continue, including the natural adaptation responses of species (Mackey et al. 2008). Corridors help retain options and opportunities for species to disperse and migrate across landscapes, for example in response to climate change. Corridors can also minimise the potential for parks to become islands and ecological ‘sinks’ in a sea of developed lands. The Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) corridor of the USA and Canada (for example) through the actions of dozens of conservation groups and land trusts is working to maintain natural interconnections between Yellowstone National Park and the Rocky Mountains national parks of Canada. The aim of this wor...