![]()

1

MYTH AND LEGEND

Almost everyone who has ever written anything about albatrosses has waxed lyrical at some point in his or her discourse, especially when dealing with the prince of them all, the wandering albatross. There is something about this enormous bird, roaming as it does forever alone over the vast empty spaces between the continents like some sort of avian Flying Dutchman, that conjures up all sorts of romantic and dramatic images in the human observer. It’s a failing I’m prone to myself, and it seems to make sense just to roll with it and get it out of the way right upfront.

I have watched peregrine mothers teaching their young to hunt, and it is indeed a spectacular sight. I have watched golden eagles soaring in Alaskan mountain wildernesses so preposterously wild and grand it brought tears to the eyes. I have watched the blue bird of paradise in full courtship display in Papuan mid-mountain oak forests – it is truly jaw-dropping. As a boy I’ve seen snow geese surging north in spring over the Canadian prairie in flocks tens of thousands strong, overhead a shattering thunder of wings, their more distant squadrons like smoke on the horizon. But I have also watched wanderers storming along in a Force 7 gale in the depths of the Southern Ocean, and I have to say I find it impossible to imagine that anything could be more impressive, while still clad in feathers. The wanderer is the ultimate seabird, the ultimate flying machine. He owns the wind. He is the Storm-Rider. It is not easy to be entirely unmoved by a wanderer.

The thing is, it’s not all myth and legend and over-dramatic froth. The wandering albatross is an extraordinary bird by any objective standard. It is the largest living thing in the air. It has the lowest ‘cost of flight’ of any flying animal. Its reproductive cycle is longer than that of any other bird. It is the most mobile creature on the planet: nothing else can move so far so fast. Thanks to numerous television wildlife documentaries, many of us are aware that the cheetah on the plains of Africa went through an ‘evolutionary bottleneck’ some thousands of years ago and in consequence has a vastly impoverished gene pool – but the wanderer has the smallest gene pool yet found in any vertebrate animal. It is even of interest to mathematicians because in its searches for food it exhibits the only example of an abstruse theoretical concept called a Lévy path yet found in any living system (no, we won’t go there). And the bird is of special interest to zoologists because in its lifestyle it crowds the outer limits of what it’s possible for an animal to do.

This book is about albatrosses rather than any particular species of albatross. Throughout the exploration of the bird and its world that follows, the focus is on those things that make the albatross unique rather than the things that merely distinguish one species of albatross from another. The wanderer gets mentioned perhaps more frequently than any of the others. I have no difficulty confessing that the wanderer happens to seize my own imagination more vividly than any of the others, but there’s more to it than that. The wanderer is undeniably the flagship of the albatross fleet, in the sense that in nearly everything an albatross does that makes it an albatross the wanderer goes just that one step further.

Late last century two things affecting albatrosses occurred. The 1980s saw a catastrophic population collapse when albatrosses came in contact with something new brought in by the world’s fishing fleets (explored in Chapter 8). A decade or so later technology made it possible for detection devices to be strapped to albatrosses and for them to be spied on from satellites. Both events, separately and in combination, provoked a surge of research interest in albatrosses, and both – for a variety of reasons – impinged most heavily on the wanderer. Several albatross species, notably the Laysan albatross in Hawaii and the royal albatross in New Zealand, have been intensely studied at their nests for five decades or more, but since around 2000 we now know a huge amount more about all the other aspects of their lives at sea. This is especially so in the wanderer’s case. Overall it could be argued that the wanderer is now better known, across all aspects of its biology, than any other albatross, so it seems to make sense to let it serve as spokesman, so to speak, for all members of the group. Moreover, the albatrosses constitute an extremely compact group and, to an extent perhaps unusual among birds, almost any interesting statement true of one species could be applied to any of the others, if you are willing to tolerate just a little squeezing and moulding and fuzz around the edges.

There is another relevant consideration. Reduced to baldest possible terms, the world of albatross specialists is currently divided into two camps: those who declare there are 13 species of albatrosses (and their supporters), and those who declare there are 24 species of albatrosses (and their supporters). Albatross taxonomy is complicated – well, not really (as I hope to show), but it’s undeniably a confused and fluid situation. As this book is essentially about albatrosses rather than any particular species of albatross, the taxonomic debate is largely irrelevant. This text seeks to go around the issue rather than through it. However, in Chapter 2 we’ll tiptoe into the taxonomist’s arena and remain just long enough to pick up a general impression of at least the size and shape and flavour of the debate, but for the most part we’ll leave it alone. References to particular species in this book are deliberately casual and informal. In those few cases where it really is vital to be absolutely specific I adopt the convention of using only the name (exactly the name) from column four in the table on page 114. But wherever it seems to me possible and appropriate, in these pages wanderers are given special licence to wander on and off the stage as they please.

Albatrosses belong to an order of birds called the Procellariiformes. This assemblage also includes the fulmars, petrels, shearwaters, storm-petrels and diving-petrels, which have in common a number of features otherwise unusual among birds. In this order, for example, are found the only genuinely pelagic birds. Most of the birds we conventionally consider seabirds are in fact birds of the coast, seldom or never leaving sight of land, but the reverse is true of albatrosses and their kin. These birds must come ashore to nest, but otherwise they remain far out at sea, sometimes for years at a time. The group also has the greatest size diversity of any order of birds – that is, the ratio in physical measurements of the largest member to the smallest is greater than in any other group of birds. The largest albatross has a three-metre-plus wingspan, whereas the smallest, a storm-petrel, is little bigger than an ordinary starling. One distinctive – in fact diagnostic – physical feature is the presence of two tubes that sit side by side on the upper bill, close to the base. This feature, which is linked with the dumping of excess salt from the blood, leads to the common name ‘tubenose’ often used to refer to the group as a whole.

In order to evolve a successful life strategy that exploits the foraging resources of the deep ocean, the tubenoses have had to confront a challenge nearly unique among birds. Indeed, it is not easy to find a truly comparable instance anywhere else in the animal kingdom. In a word, seabirds need to be extremely mobile; they have to travel great distances to gather food that by its very nature is widely scattered across even greater distances. But the real catch emerges when nesting season rolls around. Even the most oceanic of birds must perforce return to land to lay their eggs and rear their chicks. It is unusual for a typical land bird, on the one hand, to need to travel more than a kilometre or two from its nest to find food for its young. But even coastal birds often need to travel tens or scores of kilometres, and those tubenoses that forage over the deep ocean must commute hundreds or even thousands of kilometres from their nests to find food for their young and fetch it safely home. It is this steep escalation in what might be termed ‘commuting costs’ that is the pivotal factor in understanding the behaviour of seabirds and the way in which they organise their lives. It is not the finding of food, so much as the carrying of it.

All this throws a premium on the development of fast, efficient, effortless flight. Nearly all of the tubenoses have evolved, to a greater or lesser extent, and each in its own particular fashion, behavioural and physical characteristics that in effect respond to the challenge by finding ways of reducing muscular exertion while allowing the wind to do as much of the work as possible.

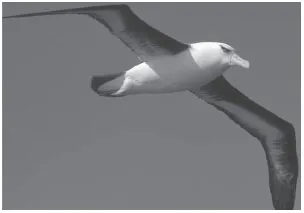

The albatrosses are those tubenoses that have gone the farthest down this particular evolutionary pathway, having very nearly abandoned powered flight altogether. They have turned themselves, you might almost say, into the ultimate super-efficient high-speed gliding machines.

In the Western world, the albatross was entirely unknown until the earliest Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and English explorers set off in search of a sea route to the fabled Spice Islands of the East in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The earliest written mention of the bird in English seems to be contained in the Elizabethan privateer Sir Richard Hawkins’ account of one such voyage in 1593, where he noted ‘certain great fowles as big as swannes, soared about us’, adding that their wingspan was ‘about two fathoms’ (quoted in Markham 1878). These birds were clearly albatrosses, perhaps wanderers. Early mariners had nothing in their traditional bestiaries to guide them in deciding what manner of bird these unknown ‘great fowles’ might be, and early guesses tended to alight on the pelican (itself an exotic creature at the time) as the new bird’s closest relative. Somehow the Arabic word for pelican, transmogrified into Western languages (through Spanish via Moorish influence) as alcatraz, became linked to the bird. By the close of the eighteenth century the bird, its name now anglicised to albatros or albatross, had become firmly established in English language and culture, with its own large body of folklore.

With their long, super-efficient wings, albatrosses are among the very few birds able to travel far from land and roam the furthest reaches of the world’s oceans.

In 1758, the first albatross (the wanderer, as it happens) was formally introduced to Western science when it was named Diomedea exulans by the Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus. The epithet exulans comes from the same ancient Greek word that lives on in modern English as ‘exile’, meaning homeless or wanderer. The generic name Diomedea was not at first particularly linked with the albatross by Linnaeus, who associated it with several other (unrelated) birds in his concept, but even here the resonances, though fanciful, are intriguingly apt. Linnaeus selected his name from classical Greek legend. One of the prominent figures in Homer’s Iliad, Diomedes served with Odysseus and Palamedes as commanders of the Greek army that sailed with Agamemnon to lay siege to Troy and to recover the abducted Helen. According to Greek mythology, Diomedes later offended the goddess Athene, who gave effect to her displeasure by conjuring up a ferocious storm at sea to wreck his fleet. In one version of the legend she turned him and all his drowned men into large white birds; in another version he survived to live out his life in exile at the court of King Danaus.

It is far from clear just how the albatross acquired its profound spiritual connotations in English folklore. For most literate folk the link is epitomised in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a harrowing tale of murder, penance and redemption that quickly became one of the landmarks of English literature after its publication in 1798. In this fantasy, the murder occurs when the Ancient Mariner kills the bird of good omen, the Albatross, the bird ‘that makes the breeze to blow’, with the result that the vessel is becalmed and the crew all die of thirst. But where did Coleridge get the core idea of the albatross as an omen? Coleridge himself described the work as purely imaginative, although historians later forged an intriguing link by uncovering the fact that one of Coleridge’s early schoolmasters was William Wales, who had in his youth sailed as astronomer and meteorologist with Captain James Cook during his second voyage of 1772–1775. At the time, exploration of the Southern Ocean was in its infancy, the exploits of the early mariners had seized the public imagination and popular accounts of their voyages were on the best-seller lists of the day. Even so, it seems remarkable that the symbol of the Southern Ocean, the albatross, had, within a few decades, so quickly established a place in the superstitions of the ordinary seaman. This association continued at least well into the nineteenth century: in the maritime folklore at the time of the Tall Ships (the clippers racing from China to home ports in England with their precious cargoes of tea) one of the myths that crops up frequently is that old sailors who die at sea are reborn as albatrosses.

Two characteristics above all others quickly captured the public imagination: the albatross’s great size, and its ability to cover enormous distances with seeming effortlessness.

Albatrosses spend nearly their entire lives on the wing. There is something compelling, almost hypnotic, about loafing against the rail of a vessel at sea watching an albatross wheeling and soaring in the ship’s wake as it follows the vessel for hour after hour, something akin to staring into the embers of a dying campfire. Generations of early mariners had similar experiences – but even the earliest of them sometimes noticed, or thought they noticed, something else again. It often seemed to them that they were staring at the same individual bird, so doggedly trailing the vessel for hour after hour. Some even noted the experience of coming up on deck the morning following such an observation, to be greeted by the sight of what they became intuitively convinced was exactly the same individual, still escorting the vessel. Sometimes an idiosyncratic feature of the bird – a missing wing feather or some such detail – served to strengthen the impression. Occasionally the intuition could be reinforced with a little more rigour. Sometimes it was possible to catch the albatross with a baited hook and line, to be hauled ignominiously aboard, marked in some way (a quick daub or two from a bucket of tar was often the most convenient method in the days of wooden sailing vessels, when such artefacts were nearly ubiquitous), then released. Often enough, the exercise proved sufficient to confirm that it was indeed the same bird following along, day after day, sometimes for a week or more.

In his monumental thesis on the oceanic birds of South America, Robert Cushman Murphy relates an incident that conveys the essential point so vividly that it has been retold many times since, and bears retelling here. The archives of Brown University Museum in America hold a manuscript that reads:

Dec. 8th, 1847. Ship ‘Euphrates,’ Edwards, 16 months out, 2300 barrels of oil, 150 of it sperm. I have not seen a whale for 4 months. Lat. 43°S., long. 148°40’W. Thick fog, with rain. (Quoted in Murphy 1936)

This terse message was found in a small container tied to the neck of a wandering albatross shot off the coast of Chile at 45°50’S, 78°27’W on 20 December 1847. Conceding the accuracy and precision of the stated dates and locations, the bird had thus flown, point-to-point, 5837 kilometres in 12 days.

This extraordinary mobility, the astonishing ability to cover enormous distances in a matter of days, very soon became firmly established as one of the key elements in Western folklore surrounding the albatross, and in particular the wanderer. Folklore, in this particular case, that was founded firmly in fact, although that was not to be finally and unequivocally demonstrated until the deployment of advanced satellite technology late in the twentieth century.

The albatross is indeed the largest of all flying creatures, but only if wingspan is deemed the decisive criterion. If the judgement is to be decided by mass or weight, then several among the various species of swans, cranes or pelicans have legitimate claims that need to be evaluated. A mature male wandering albatross may weigh as much as 11 or 12 kilograms, seldom more. On the other hand, in northern Europe it should not be too difficult to find a mute swan of comparable age and gender that matched such a bird in weight, and some have been recorded at two or even three kilograms heavier still. Similarly, recorded weights for the Dalmatian pelican range up to 13 kilograms. There are several other possible contenders in this general class of super-heavyweights among birds.

When it comes to wingspan the picture is much clearer, though not entirely so. A mature male wanderer has a wingspan comfortably in excess of three metres. Nothing else even comes close. Except another albatross, that is. The fact is, the two ‘great’ albatrosses, the wanderer and the royal albatross, are so closely matched in size that any genuine differences are occluded by the cloud of uncertainties necessarily attendant on any attempts to measure them. Another quote from Robert Cushman Murphy conveys one aspect of the difficulty:

Finally I may report that the same figure (11 feet 4 inches or 345.4 centimetres) was the greatest ex...