![]()

Chapter 1

What is skin cancer and how does it form?

David Whiteman and Catherine Olsen

Key messages

• Australia and New Zealand experience by far the highest rates of skin cancer in the world.

• Excessive sun exposure is the most likely cause of the large majority of skin cancers, so the majority of skin cancer is preventable.

• Keratinocyte cancers (abbreviated here as KCs, and also commonly referred to as non-melanoma skin cancers or NMSCs), are by far the most common form of skin cancer.

• Melanomas are less common than KCs, but are responsible for the most deaths from skin cancer.

• People with lighter skin colours are at higher risk of skin cancer compared to people with darker skin colours.

• Family history influences skin colour and plays a major role in determining who is at higher risk of skin cancer.

• People with a past history of BCC and SCC have about a three-fold higher risk of developing melanoma than the population average.

Apples and oranges: the different types of skin cancer

What is the skin, exactly?

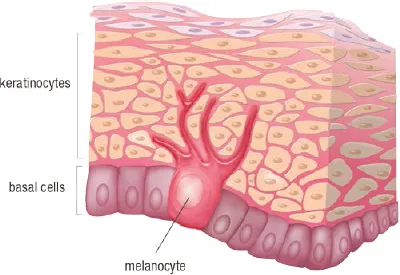

The skin is the largest organ in the body, and performs many different functions. The skin is our outermost protective barrier – its job is to keep out germs, toxins, radiation and a host of other nasties in the environment. The skin also regulates our temperature – keeping us warm in winter and cool in summer. To perform its many functions, the skin is made up of different types of cells in different layers (see Fig. 1.1). The outermost layer is called the epidermis, and it mostly contains flat cells called keratinocytes. It is these cells, the keratinocytes, that dry out to form the flaky outermost layer of keratin. Keratin is also used to form hair and nails. Another common cell found in the epidermis is the pigment cell or melanocyte, so called because it produces melanin. Melanin is the compound that tans our skin and gives freckles and hair their distinctive colours. Other cells found in the epidermis include sensory cells and immune cells.

The next layer down is the dermis, which contains fat, nerves, blood vessels and the bundles of fibres which give the skin its strength and flexibility. Below the dermis are the deeper fat layers. Between the epidermis and dermis is a very thin membrane, which forms a very important landmark for describing skin cancer. Cancers that are contained wholly within the epidermis and which have not crossed the boundary into the dermis, are considered pre-invasive cancers. That is, they are cancers that have not yet invaded into the deeper layers of the skin. Such cancers are considered to be very early stage cancers. Their technical name in Latin is in situ, which means literally ‘in position’ or ‘in its natural place’. In contrast, invasive skin cancers are those which have spread from the epidermis and crossed the boundary into the dermis.

Fig. 1.1: The epidermis as viewed under a microscope. ©QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute.

Cell division

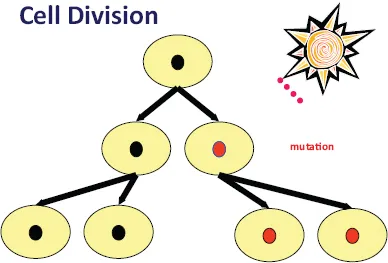

As we go about our lives, we are constantly shedding skin cells. Each and every day, we scrape and scratch and damage our skin. To replace the cells that are being lost and to prevent our skin from being worn away completely, the skin cells undergo an orderly process of cell division (which scientists call ‘mitosis’). In this process, a ‘mother’ cell in the lowest layer of the epidermis divides into two ‘daughter’ cells. Each daughter cell is an exact copy of the mother cell and contains all of the genetic material that is needed to function as a skin cell. The process of cell division is under extremely tight control to make sure that each new cell is a perfect copy of the original. This control also makes sure that cells divide only when they are supposed to. Sometimes, however, the genetic material inside a cell is damaged, for example by exposure to ultraviolet radiation in sunlight or by infection with a virus. These types of events can mutate (or disrupt) the genes inside the cell. Because each daughter cell is an exact copy of the mother cell, a mutation that occurs in a gene in the mother cell will be passed on to the daughter cells (Fig. 1.2). Many mutations have no bad effects, and some mutations can even have good effects. However, if a mutation occurs in one of a very small number of genes that are critically important for mitosis, then it can have very bad effects. For example, some mutations can make a cell keep dividing when it is not supposed to, leading to uncontrolled, continuous cell division. This type of uncontrolled behaviour is the classic feature of cancer. This is why cancers are sometimes called ‘growths’ – quite literally, the relentlessly dividing mass of cells leads to a big lump of growing tissue.

Fig. 1.2: The process of cell division. Here, one of the daughter cells has developed a mutation as a result of high-energy wavelengths of sunlight. This mutation is then passed on to the next generation of daughter cells.

Cancers of the skin

Any of the cells that are found in the skin can, at least in theory, form cancers. By far the most common cancers are those that arise from the keratinocytes. Keratinocyte cancers occur as two main types called basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These two types of skin cancer earn their names because of how they appear when viewed under a microscope.

BCCs are the most common of all cancers in humans. They typically occur from the middle decades of life, and become more frequent with age. While most common on the face, scalp and neck, they also occur on the trunk and limbs. These cancers are often first noticed as a lump or sore on the skin that does not heal. Another name for BCCs is ‘rodent ulcer’. This name describes their appearance (i.e. an ulcer on the skin usually with rolled edges), as well as their tendency to burrow into the skin. Fortunately, most BCCs grow quite slowly and can be treated very effectively.

SCCs are the second most common cancers in humans. They tend to occur on parts of the body that get lots of sun, such as the face, ears, neck, scalp and arms. They are very rare on body parts that are not exposed to the sun. Like BCCs, they often come to attention as a skin sore, but they tend to grow more quickly than BCCs. In rare cases, they can invade the bloodstream and spread through the body. For this reason, it is important to treat them early.

Melanomas are cancers that arise from the pigment cells of the skin. These cancers usually come to attention as a ‘funny mole’ on the skin. They are noticed most often because they have changed in colour or shape or feel. While melanomas are often dark in colour, some can be light-coloured and so can be difficult to see on the skin. Melanomas can arise anywhere on the body but the greatest numbers occur on the back; many also arise on the legs, arms and head. Melanomas can grow and spread to other parts of the body very quickly, so it is important to diagnose them early.

Other types of skin cancer include Merkel cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, various lymphomas and other rare types. Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare but highly aggressive skin cancer, which forms from Merkel cells. Merkel cells are also found in the epidemis of the skin. It was recently discovered that most of these cancers appear to be caused by a virus (the so-called ‘Merkel cell polyomavirus’). Merkel cell tumours can be flesh-coloured, pink or blue, and usually present as firm painless nodules.

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a tumour that used to be very rare but became much more common during the 1980s with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Unlike the other cancers of the skin, Kaposi’s sarcoma does not arise from keratinocytes or melanocytes in the epidermis, but from the cells that line lymph or blood vessels.

The abnormal cells of KS form purple, red or brown blotches or tumours on the skin. Interestingly, these cancers are also caused by a virus, in this case, the human herpes virus 8 (HHV8). This virus is reasonably common and actually does not harm people, unless their immune system has been damaged (e.g. following infection with HIV).

Why all the fuss? The burden of skin cancer

Skin cancers impose a massive toll on the Australian population. Indeed, it is hard to overstate the burden from these diseases. The bald statistics make for sober reading. Each year, more than 400 000 Australians develop at least one BCC or SCC – that’s more than 1000 people every single day of the year. Skin cancers are so common that they account for more than 80% of all cancers diagnosed in Australia. They impose the highest costs on the Australian health system of any cancer type. More than 750 000 treatments for skin cancer are billed through Medicare each year, costing the Australian government more than half a billion dollars. (These costs do not include the very large out-of-pocket expenses to patients that add to the total bill, such as gap payments to doctors and the costs of dressings, painkillers, time off work etc.) By 2015, the figures are predicted to rise to nearly 1 million skin cancer treatments at a cost to Medicare of $703 million. Often mistakenly thought of as trivial cancers, BCCs and SCCs cause enormous ill health and, unfortunately, kill many more people than we might realise. Each year in Australia, BCCs and SCCs lead to 85 000 hospital admissions (more than twice the number of admissions for each of bowel, breast or prostate cancers) and cause 500 deaths. BCCs are rarely fatal; most deaths from keratinocyte cancers are due to SCCs.

Melanomas add to this terrible burden. In 2012, more than 200 Australians every week were diagnosed with these dangerous skin cancers, resulting in an annual total of more than 11 000 people with new melanomas. Not counting BCC and SCC, melanoma is the third most commonly occurring cancer in Australian men (after prostate and bowel cancers) and women (after breast and bowel cancers). The rate at which Australians develop melanoma is the highest in the world.

Each year, out of every 100 000 people living in this country, 57 will be newly diagnosed with melanoma. This is much higher than the rate of melanoma observed in other western countries such as the USA, UK, Canada and Sweden. Only our nearest neighbour, New Zealand, has a rate of melanoma approaching that of Australia, affecting ∼41 people out of every 100 000.

Melanoma has a higher death toll than other types of skin cancer. Each year, more than 1500 Australians die from this disease, making melanoma deaths more common than road fatalities.

Trends over time

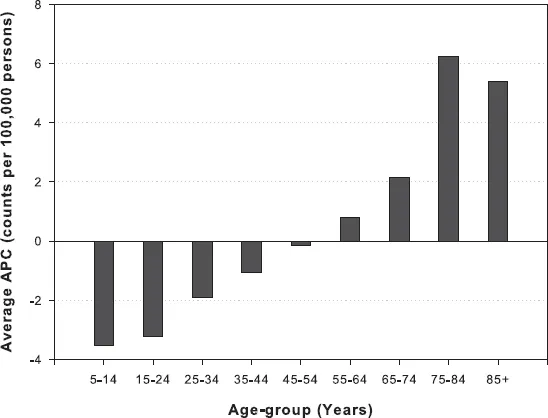

Many health systems (including every state in Australia) maintain registries which are notified whenever a person living in a particular region is diagnosed with cancer. Such cancer registries are very important for monitoring trends in cancer occurrence, as well as to assess patterns of care, treatment services and cancer survival. While cancer registries aim to capture information on every diagnosis, the fact is that only a very small number of registries anywhere in the world record information about BCC and SCC (this is because BCC and SCC are three to four times more common than all other cancers combined, and collecting information on them would use up all the resources of a cancer registry). In Australia, it has been possible to monitor trends in BCC and SCC through analysis of Medicare records (Medicare is the universal health insurance which reimburses doctors for the costs of treating patients). Medicare makes payments depending upon the size of the skin cancer, its location on the body and the complexity of treatment required. A very recent analysis has shown that while treatment rates for BCC and SCC continue to climb rapidly among older Australians, the numbers of treatments for skin cancer among younger Australians (under 45 years) are beginning to fall (see Fig. 1.3). It is thought that these declines may reflect the impact of sun protection campaigns which commenced in the 1980s.

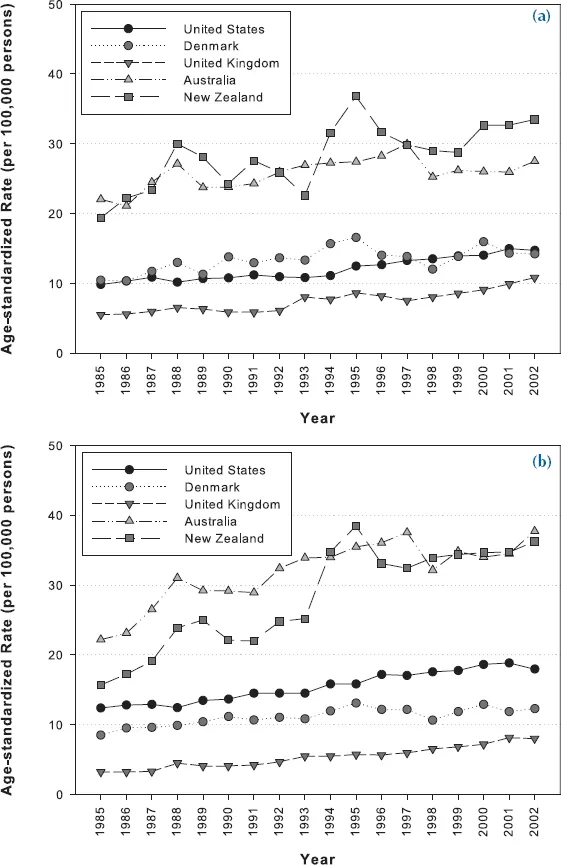

All cancer registries record diagnoses of melanoma and it is true to say that, almost without exception, melanoma rates have been rising in all populations with European ancestry (Fig. 1.4). Depending on the population, some have observed differences by sex (e.g. increased rates in men rather than women), by body site (e.g. rapid increases on the back and trunk in some regions, but not in others), or in particular age groups (particularly in older men). Monitoring such trends is extremely important to identifying shifts in the patterns of skin cancer, so that doctors and health workers can target resources to those at highest risk.

An important observation is that deaths from melanoma have not risen nearly as rapidly as diagnoses of melanoma. For example, in the USA, diagnoses of melanoma increased about five-fold between 1950 and 1990, whereas melanoma deaths increased only slightly less than two-fold during the same period. Similar observations have been made in western and northern Europe. In Australia, the most recent data suggest that deaths from melanoma remained stable between 1989 and 2002 for men, and declined for women (-0.8% p.a.). When looking at melanoma death rates by age group, it was found that rates were lower among people aged less than 54 years and were static among those aged 55–79 years, but continued to rise among those aged 80 years and older.

Fig. 1.3: Average rate of change of skin cancer treatments by age group. Source: Data from Medicare Australia 2000–2011.

Another notable feature of recent melanoma trends around the world has been the rapid rise in the incidence of in situ, thin and early stage melanomas. Such increases have led some to suggest that the recent increase in melanoma may be due to overdiagnosis – that is, skin lesions are now being called ‘melanomas’ that would have been called ‘funny moles’, or not diagnosed, in the past. There are arguments for and against this notion, but most researchers agree that even if there has been some overdiagnosis of melanoma, it does not account for all the increase that has been seen during the past few decades.

Fig. 1.4: (a) Melanoma incidence trends over time in white populations – females. (b) Melanoma incidence trends over time in white populations – males. Source: Data from Ferlay et al. (2010).

Who gets skin cancer?

BCCs, SCCs and melanoma are overwhelmingly cancers of fair-skinned people – especially those who trace their ancestry to northern Europe. While cancers of the skin do o...