![]()

1

A focus on citizen-led action

Paul Martin and Autumn Smith-Herron

Invasive species pose a major risk to the environment, industry and health: invasive species – pests, diseases and weeds – threaten agriculture and forestry, native species, natural regeneration and ecosystem resilience. They already have a massive environmental, social and economic impact, and climate change is likely to enable new invasive species to thrive. (Cresswell and Murphy 2016, p. v)

This quote from Australia’s 2016 State of the Environment report summarises a significant challenge: the management of the increasing harms from invasive species. Harms caused by invasive species are increasing in Australia – where it is one of the five major threats to biodiversity, and a significant cause of economic cost – and this is true around the world. As human beings move around the planet, they take with them plants, animals, viruses, fungi and single-celled protists, which including moulds and protozoa. The reasons for this movement of species include: to provide food, fibre and fuel; to recreate aesthetic or other conditions from other places; to collect and display exotic species; or to achieve environmental or production benefits. However, often the relocation of species has been accidental, such as the introduction of the black rat and the many European weeds introduced into the New World. Unfortunately, many of the introductions, whether intentional or not, have been harmful to the receiving environment or to human welfare.

The Global Invasive Species Database records invasive species from around the world: animals (364), bacteria (8), fungi (19), plants (467), protista (30) and viruses (29). Including animal diseases to the database would add a significant number of harmful invasive species. The 100 of the Worst report illustrates that invasive species have many deleterious effects, including impacts on primary production, on the environment and on human and animal welfare (Doherty et al. 2016; Early et al. 2016; Low 2017; McGeoch et al. 2011; Paini et al. 2016). Very harmful creatures can be found in every taxonomic category, including: plant diseases and parasites that reduce production or crowd out beneficial species; invasive grasses and trees; aggressive ants and other insects; and mammals such as rats and feral pigs (Lowe et al. 2000).

This chapter first considers in more detail the costs of invasive species to the economies and social welfare of Australia and the US, and then discusses the institutional issues that ‘frame’ the management of invasive species. Institutions shape roles and obligations, and what resources can be obtained; they also largely determine how (or whether) the work of citizens is coordinated and supported by government and industry. This chapter makes the point that institutional arrangements are not distinct from community action: they are part of it because of the significant impacts they have on citizen roles and obligations, resources and coordination.

Invasive species: the costs to Australia and the US

As is the case in many other parts of the world, Australia and the US have experienced inexorable increases in invasions, despite their substantial investment and efforts to manage the invasive species challenge. Table 1.1 lists the numbers of invasive species known to exist in the two countries.

Any measures of invasive species presence and impacts is imprecise because of fluctuations over time and space and the difficulties of measurement. For example, contrasting with the figures provided in in Table 1.1, Pimentel et al. (2005) estimates that 50 000 exotic species occur in the US alone. Not all introduced species cause significant harm, however, and some provide human services. Some species are important to our economy (e.g. horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, deer and poultry) or be beneficial agricultural crops (e.g. maize, wheat, rice and sugarcane).

Table 1.1. Numbers of invasive species in the US and Australia.

| Species | US | Australia |

| Animals | 267 | 136 |

| Plants | 350 | 263 |

| Other invasive species | 29 | 12 |

Source: Invasive Species Database, http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/

In Australia, invasive species have been identified as one of the three main threats to biodiversity under the National Biodiversity Strategy, prepared as part of Australia’s commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (National Biodiversity Strategy Review Task Group 2010). That strategy highlights community engagement as central to all forms of biodiversity protection, including invasive species management, and many programs are used to try to motivate and enable citizen action (Department of the Environment 2014).

Notwithstanding these efforts, national state of environment (SOE) reports and other studies show that Australia continues to face deteriorating invasive species conditions. The recent 2016 SOE (Cresswell and Murphy 2016, p. 8) report for Australia summarises the situation as follows:

The pressure from invasive species and pathogens continues a very high and worsening trend. Invasive plants and animals are the most frequently cited threats to species listed in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, and account for 12 of the 21 identified key threatening processes. Almost all states and territories note that data on the distribution and abundance of pest plants and animals, and management effectiveness for these pests are poor.

Additional to the biodiversity impacts are the economic costs of invasions. It is hard to provide an accurate figure on the total impact. A 2016 study of the revenue and control costs of weeds to Australian grain growers put this impact at A$3.32 billion (Llewellyn et al. 2016). Another study conducted by the grains industry estimates the cost of weeds to grain production exceeds A$3 billion each year, and the risk management value of biosecurity is thousands of dollars each year for each Australian farm (Hafi et al. 2015). A NSW government committee calculated the annual costs of rabbits, carp, pigs, foxes, wild dogs, goats and introduced birds in NSW at A$170 million, and a national national economic impact of A$720 million to A$1 billion (NSW Natural Resources Commission 2016). A scenario-based analysis of the costs of selected pest animals to agriculture indicates a national range of between A$416 million and A$797 million per annum (McLeod 2016). If a value for biodiversity impacts and if the risks of potential invasive species impacts was included, the economic extent of the problem would be even greater.

The types of impact in the US are similar. The reported costs associated with invasions include detection (survey) efforts, costs associated with land management practices and habitat preservation of beneficial native species. Intentional or accidentally introduced non-native species invade native communities and predate (by browsing and grazing), compete for limited ecological resources, reduce the likelihood of native tree regeneration (Tyler et al. 2006), introduce disease and parasites, hybridise, and create en vironmental chain reactions that reduce natural diversity (Temple 1990). For example, many plants introduced into the US for food, fibre or ornamental purposes have escaped and established into natural ecosystems. These are outcompeting native plant species at an alarming rate (Morse et al. 1995). The introduction of vertebrate animals into new areas is typically human related (Pimentel et al. 2005). Some of these (domestic cat Felis catus; domestic dog Canis familiaris) are pets whose feral descendants become a threat to native species such as amphibians, reptiles, birds and small mammals, and to farmed livestock.

The negative effects of invasive species on US industry, including on international trade, forestry, fisheries and power production is counted in the billions of dollars each year (Lovell and Stone 2005). A recent study by the US Weed Science Society of America indicates that, should weed control methods fail or be unavailable through legal restrictions, removal from the market or resistance, the potential economic losses of corn and soybean crops in North America could exceed US$40 billion each year. As already mentioned, the risk of invasion is accelerating because of new transport systems that help to increase trade and tourist activities (García-Llorente et al. 2008).

Institutional frameworks for citizen action

Increasing international concern about invasive species impacts is reflected in the Aichi Convention, Target 9. The ratifying countries have committed in principle that ‘[b]y 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment’ (Convention on Biological Diversity 2016).

This reflects a general understanding that invasive alien species cause significant biodiversity loss and threaten food security, human health and economic development. It is likely that, partly because of increased human travel and trade, the adverse effects of invasive species will increase regardless of policy goals or instruments. Because the methods used to control this major problem are not sufficiently effective, significant innovation is needed to get better results.

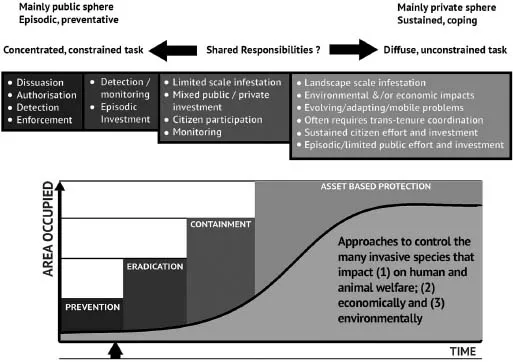

The prevention or control of invasive species harms requires action at many levels (see Fig. 1.1). The first level is to prevent additional invasive species entering an uncontaminated area or becoming established in that area. The second level is response strategies intended to eliminate unwanted species as soon as possible after they are detected. The third level is ongoing management to control the harms once species have become established in an environment. These activities each require specialised research, administration, regulation, investment and other actions. The strategies, instruments, roles and stakeholders are different for preventative biosecurity (e.g. federal government management through customs quarantine), incursion response (e.g. state and local biosecurity emergency response teams) or ongoing pest animal or weed control (e.g. regional community-based natural resource management programs).

Fig. 1.1. Generalised invasion curve.

The nature of the issues along the invasion curve dictates what roles are played by government and by community organisations. Customs and policing activities require the power of the state, and biosecurity emergency response is likely to require powers and specialised skills most likely to be found in government – though incursion responses often aim to involve industry and community groups in a government-coordinated program. Different specialisations and organisations are involved, depending on whether the risk is to human health, to farming, to animals or to the environment, with the nature of potential impacts indicating what organisations are likely to be involved. When threats are potentially economically or environmentally catastrophic or affect human health, direct government action is often required. However, when the challenge is to control established (non-catastrophic) invasions, government is likely to rely more heavily on citizens and non-government organisations. The first reason is the many practical constraints on the ability of governments to take action. Many harmful established invasive species occur across large areas, and their control requires a substantial and sustained investment of labour and resources. Governments do not have enough human and financial resources to do this, and political dynamics make it difficult to ensure ongoing investment in any public program. Theory and experience also suggest that control of established invasions is best carried out by people who are ‘on the spot’ and who are likely to be aware of what is happening in their landscape. They should be better equipped to intervene early and to minimise the harm at a lower cost than if the work is carried out by government agencies, who carry an unavoidable bureaucratic overburden and transaction costs. In times of budget constraints and increasing demands on public investment, government agencies are finding it harder to provide the funds and other resources for large ongoing programs. They are finding ways to limit that involvement, which means that the load must be picked up by the non-government sector, or it means that the work is not done and problems remain under-managed.

The institutional arrangements at each level of government also vary depending on whether the impacts are likely to be catastrophic or merely chronic, and whether the primary impact is upon the environment, human uses of the environment, or animal or human welfare. For example, detection of a serious disease that can spread rapidly ...