![]()

Chapter 1

Setting the scene: water and vegetation resources in Australia

This chapter provides a broad overview of the water resources and vegetation of Australia. The chapter starts with a review of surface and groundwater stores and their uses. We present a continental-scale water balance and highlight the fact that Australia is precariously balanced in its water use. Vegetation resources and the factors that influence vegetation structure and function are then described. In particular, the influence of climate (especially rainfall) and the Southern Oscillation on variability of rainfall and the adaptations that vegetation has evolved in order to cope with the Australian climate, are discussed. Finally, we show that simple vegetation classification systems can be applied to almost all Australian landscapes and explain how such systems have direct relevance to ecohydrology and allow effective communication between hydrologists and ecologists. Changes in Australian landscape hydrology are primarily a function of changes in landscape use, especially changes in land cover, and therefore a brief comparison of pre-and post-European colonisation vegetation cover is made.

After reading this chapter, readers should be familiar with the following topics:

- the amount and fate of rain that falls on the Australian continent;

- the major uses of water in Australia;

- the principal climate zones of Australia;

- the Southern Oscillation index;

- sclerophylly and other adaptations to the Australian climate and soils exhibited by Australian plants;

- distinguishing features of Australian soils;

- foliage projected cover: life form, stratum, leaf area index, structural and functional attributes of vegetation;

- a classification system for vegetation types in Australia;

- vegetation change over the past 200 years.

Introduction

A broad knowledge of the water and vegetation resources of Australia is a necessary prelude to a text on the ecohydrology of Australia. In particular, it is important that a continental-scale context is given to water resources (both surface and groundwater) and vegetation. Because climate and soils also influence both water resources and vegetation, and because vegetation influences how water moves through the landscape, it is important to include an overview of these broad areas to act as a backdrop for later chapters. The following section provides a brief overview of the water resources of Australia. Subsequent sections in this chapter deal with climate and vegetation.

Water resources in Australia

Water resources in Australia consist of surface and groundwater stores. The supply of water to these stores comes principally in the form of rainfall (direct input) and run-off (the movement of surface water from one place to another along a slope, i.e. redistribution). Understanding these flows at a continental scale provides the background required to consider water resources at a local scale.

Rainfall and run-off

Australia is well known as the driest of all permanently inhabited continents. Mean annual rainfall is about 350–450 mm, considerably lower than the mean annual rainfall for Africa (750 mm), North America (800 mm), South America (1800 mm), Europe (820 mm) and Asia (650 mm). The total volume of water received by Australia as precipitation has been estimated to be about 3 320 000–3 390 000 GL per year (Foran & Poldy 2002). Because of the high evaporative demand of the climate (high levels of solar radiation lead to warm-to-hot temperatures and relatively dry air for much of the year) and the flatness of the continent, little of this water reaches the sea as river flow. About 350 000 GL (c. 10%) of this precipitation is lost to sea as river flow. While this seems a large number, it is the smallest fraction of total rainfall for any permanently inhabited continent (see Figure 1.1, Colour Plate 1). Much, but not all, of the water flowing in rivers is derived from run-off, that is, overland or shallow subsurface lateral flows of water. However, in many rivers, a component of river flow is derived from the discharge of groundwater (termed base flow). This is discussed more extensively in Chapter 3.

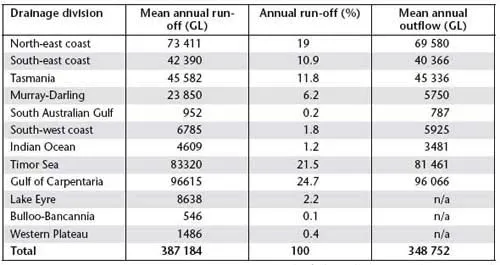

Twelve drainage divisions cover all of Australia and Table 1.1 shows the volume and percentage run-off from each of these. In six drainage divisions (half of the total), less than 2.5% of rainfall is lost as river flow. The remainder is lost as evaporation, transpiration and seepage into groundwater or other storage (lakes). The low amount of rainfall that is ‘lost’ from the continent as river flow sets an upper limit to how much water can be extracted from rivers for human use.

Table 1.1 Run-off from 12 drainage divisions in Australia

Source: Data from the Australian Water Resources Assessment (2000)

Australia’s continental water budget

Of the total volume of water received by Australia as precipitation (3 320 000–3 390 000 GL per year; Foran & Poldy 2002), about 10% is lost to sea as river flow (see above) and about 3 100 000 GL is lost as evapotranspiration, that is, evaporation from wet soil, lakes and other wet surfaces, plus transpiration from vegetation. This means that there is very little spare capacity in the water budget for new activities or for using more water in existing activities; in other words, the Australian continental water budget is precariously balanced. It also means that when rainfall is significantly below average, as is often the case in Australia, river flow and evapotranspiration decline too. Declines in river flows and evapotranspiration have three serious knock-on effects. First, river health declines when low river flows are maintained for too long. Second, a reduction in evapotranspiration results in increased fire frequency and reduced productivity (growth and yield) of crops and native vegetation. Finally, when rainfall is low there is an increased reliance on groundwater (water stored underground) for irrigation and human consumption. Too many aquifers are already being over-extracted, with extraction at rates greater than natural rates of groundwater recharge (see Table 1.3). The argument that additional water can be taken from rivers is difficult to sustain when it is accepted that the maintenance of river health is important and that doing so requires adequate river flows. There is minimal scope for taking more water from rivers of the southern half of the continent (although more could be taken from rivers in the northern half). As discussed in Chapters 6 and 8, regulation of river flows and extraction from rivers has generated significant problems for the hydrology, ecology and sustainability of many activities in Australia. There are many lessons here, regarding managing extractions and flows, that are applicable to other arid and semi-arid zones in Africa, the Middle East and Southern America.

Surface and groundwater stores

Surface water is water in rivers, lakes, dams and other locations on the surface of the earth.

Australia possesses about 450 large dams with a combined storage of about 80 000 GL. These are used principally for urban water use, irrigation and, in Tasmania, hydroelectric power generation. New South Wales has the largest surface water storage capacity, followed by Tasmania. On-farm dams are large in number (the estimate is more than 2 million) but their total volume is small – less than 10% of the total surface water stored. In addition to ‘static’ stores of surface water, the volumes of water passing out to seas in rivers are also viewed as surface water stores. However, river flows represent only a small fraction of rainfall and are highly variable between years.

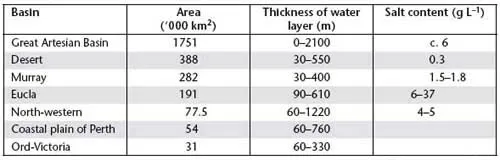

There is another store of water upon which Australia is heavily reliant – groundwater. Groundwater is water located below the surface of the earth in porous soil and rock (an aquifer). Examples of the major artesian basins, including details of their depth and salt content, are given in Table 1.2. Salt contents vary widely across each of these systems; tabular values are indicative only. Some 72% of Australia’s sustainable supply of groundwater has less than 1.5 g L–1 of salt, with an additional 16% of groundwater in the range of 1.5–5 g L–1. Groundwater can reach the surface in some locations if recharge of the aquifer is very high and the aquifer is close to the surface, or if the aquifer intersects a hill slope or cliff face.

Australia has extensive extractable groundwater reserves. The Australian Water Resources Assessment (2000) cites a sustainable yield of almost 26 000 GL nationally, and estimates that Australia currently uses about 10% of this. Note that this is an estimate of the sustainable yield of all the aquifers in Australia (see below). It is not an estimate of the total volume of groundwater in Australia, which is much larger. The Great Artesian Basin alone is estimated to store a total of 8 700 000 GL of water.

Table1.2 Major artesian basins of Australia, their areal extent, depth and salt content

Source: Shiklomanov & Rodda (2003)

Safe yield has generally been defined as the volume of water that can be extracted from an aquifer without depleting the reserves and is therefore determined by the rate of recharge (see Chapter 3). However, this is a flawed concept because in the long term, under conditions of equilibrium, natural recharge is balanced by discharge to the...