![]()

1

Challenges and opportunities for fire

management in fire-prone northern

Australia

Jeremy Russell-Smith, Peter J Whitehead, Peter M Cooke and Cameron P Yates

INTRODUCTION

In the southern summer of late 2002 through to early 2003, large bushfires ravaged somewhere between 20 000–30 000 km2 of mostly forested terrain in south-eastern Australia. The southeast corner of Australia is the most densely populated portion of a mostly arid, flammable and very sparsely settled continent. Terrifying images of huge fires sweeping onto the smoke-enshrouded outlying suburbs of Sydney – and of the fast moving inferno that engulfed over 500 homes in the western suburbs of the nation’s capital, Canberra – played out across the global media. At the time, much of southern Australia was in the grip of a prolonged and savage drought and, for an already nervous populace, these images presaged the enormity of an emerging climate-induced increase in numbers of days of extreme temperature and associated wildfire activity and diminishing regional water availability in the decades to come (CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology 2007; Garnaut 2008). The even greater loss of life and property in the 2009 fires in rural Victoria will undoubtedly drive intense re-examination of present approaches to fire prevention and response.

An important political response to the 2002/3 southern Australian fire crisis was establishment of the Council of Australian Government’s (COAG) National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management (Ellis et al. 2004). This was the first ostensibly national bushfires inquiry in a long history of such inquiries following fire ‘disasters’ in various southern Australian settings – commencing with Justice Stretton’s formative report into the Black Friday fires of 1939.

As part of its terms of reference, the COAG inquiry undertook an assessment of ‘the facts in relation to major bushfires in the 2002–03 season’. The report observed (p. 6) that whereas ‘community and media interest during the 2002–03 fire season focused on fires that affected about 3 million hectares in south-eastern Australia … in the same fire season, however, around 38 million hectares was affected by fire in northern and central Australia’. In fact, this figure represents only the Northern Territory, where, between April 2002 and March 2003, fires

affected 28.6% of the jurisdiction. Although these figures include an exceptionally large area of fire in arid central Australia in 2002 following the most significant rainfall for decades in 2001, and the subsequent build-up of flammable grassy fuels, the inquiry also noted (p. 16) that 210 000 km2 of the Northern Territory’s tropical savannas region is affected by fire in an average burning year.

Three weeks before the report’s release on 31 March 2004, two of the authors of this chapter (Peter Cooke and Jeremy Russell-Smith) – invited as representatives of northern Australian Indigenous and research interests, respectively – participated in a small ‘invited specialists forum’ to review the then close-to-complete draft document. The draft presented to us at the time reflected simply a deep lack of cultural understanding and appreciation for the vast landscape scales and resourcing issues confronting fire management in fire-prone regional and northern Australia. Among the various significant issues we documented are:

- a lack of understanding of the continental scale of, and the need to provide support for, the use of fire as a management tool for production, conservation and cultural management goals – as opposed to being concerned singularly about risk-management and emergency-response issues – especially in southern Australia

- a general lack of recognition that the largest areas of annual fires (and wildfires) occur predominantly in northern Australia – and periodically in the arid centre – and that current fire regimes are exerting significant impacts on regional biodiversity, environmental, greenhouse gas emissions, human health, social and community values. In fact, in the (subsequently amended) summary on page 1, the draft report found that, despite over a quarter of the Northern Territory being burnt by wildfires in 2002, there was ‘little detrimental impact’ in that year!

- a limited appreciation of the necessity for landscape-scale remote sensing applications for informing regional real-time fire management operations, and regional and national policy agendas

- a lack of comprehension of the national and global significance, challenges and opportunities surrounding greenhouse gas emissions from savanna burning

- a total lack of understanding of contemporary and emerging social demographic issues in regional and northern Australia: particularly opportunities and requirements for engaging Indigenous (Aboriginal) skills and knowledge in developing economically viable fire-management enterprises and partnerships.

While acknowledging that the final report did in fact begin to address several of our seemingly ‘parochial’ concerns as expressed to the meeting – and subsequently to the authors in frank correspondence – this recent national inquiry usefully illustrates a contemporary stereotypical national policy focus on bushfire management in Australia. We acknowledge that risk-management and emergency-response issues in densely concentrated southern Australian electorates are legitimate political prerogatives that need to be tackled. In response to this generic national policy myopia, however, we recognise that key challenges for the fire-prone north include: setting out a cogent and compelling case that savanna fire-management issues do warrant national attention; that we are in the process of developing novel, collaborative regional approaches for delivering environmentally, culturally and economically sustainable solutions; and that such solutions provide useful examples for fire management in various other regional, national and international savanna contexts. The obligation to communicate the elements of this case provides a first strong motivation for compiling this book.

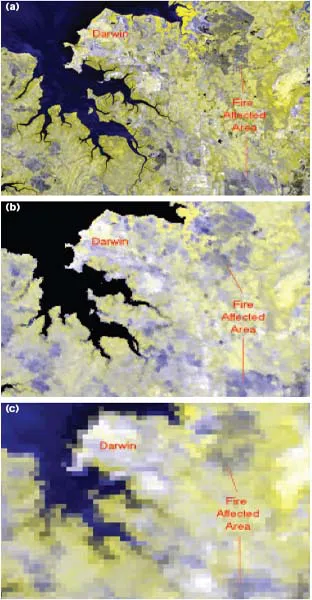

Figure 1.1 Images for the Darwin region, Northern Territory, 8 June 2008, illustrating fire-affected areas at different imagery scales: (a) Landsat, (b) MODIS, (c) AVHRR. All images display red and near-infrared bands.

FIRE MAPPING AND CONTEMPORARY BURNING PATTERNS

Our contemporary understanding of fire patterning in northern Australian landscapes has been informed largely through the application of satellite imagery at three scales of resolution. Dating back to the early 1980s, relatively fine-resolution LANDSAT imagery (pixel sizes ~0.1–0.5 ha, depending on the sensor; Figure 1.1a) has been used in a large number of regional studies – including assessments included in this book (Chapters 9 and 10) – for characterising savanna fire regimes (e.g. fire extent, seasonality, frequency, interval-between-fires and patchiness) and addressing attendant ecological, greenhouse and land-management issues. With individual scenes with a dimension of 180 × 180 km, combined with relatively high cost (at least to date) and relatively infrequent sampling (every 16 days), this imagery has been applied typically in spatially and temporally limited regional snapshots or, more rarely, in multi-scene, decadal studies of regional fire regimes such as for Kakadu, Litchfield and Nitmiluk National Parks (Chapter 10).

Since the late 1990s, continental-wide understanding of the occurrence of fires has been developed substantially from daily observations made through application of the relatively coarse resolution (~1.1 × 1.1 km pixels at orbital nadir) Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) instrument on the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) series of satellites (Figure 1.1c). Currently, assembled fire observation data derived from AVHRR are available from 1997 for the whole of the continent, and from 1990 for Western Australia and the Northern Territory (Craig et al. 2002; Meyer 2004).

More recently, a second continental-scale sensor – the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS; 250 × 250 m pixels), with purpose-built daily fire detection and mapping capabilities – has become available (Figure 1.1b). Both AVHRR and MODIS have a sample swath exceeding 2000 km in any one overpass, and both sensors enable automatic detection of active fire ‘hotspots’, and post-fire assessments and mapping of burned or, more appropriately, fire-affected areas. Hotspot data derived from both satellite sensors are routinely made available within hours of satellite overpasses on a number of Australian fire management websites:

- http://www.firewatch.dli.wa.gov.au

- http://www.firenorth.org.au

- http://sentinel2.ga.gov.au/acres/sentinel.

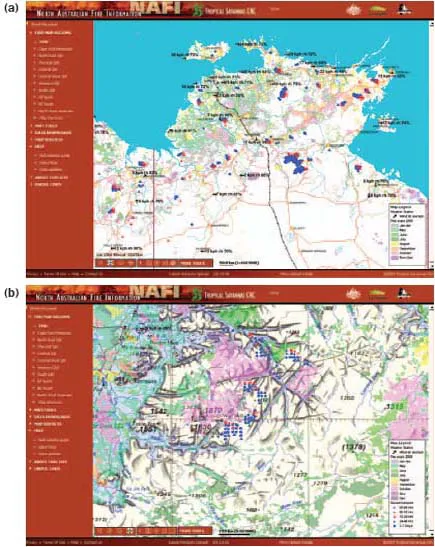

Fire-mapping products are also available from the first two listed sites. The ‘firenorth’ – or North Australia Fire Information (NAFI) website developed by the Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre – also provides fire-mapping products derived from MODIS imagery (Figure 1.2).

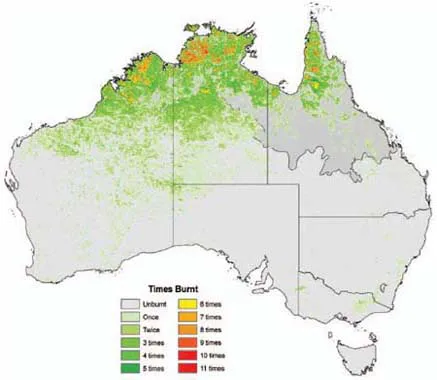

Collectively, these remotely sensed data sources and website portals have started to transform widely held misperceptions that bushfire events – and their social, environmental and economic implications – are a particularly southern Australian phenomenon. On the basis of continental mapping of large fire-affected areas (> ~2–4 km2) for the period 1997–2004 derived from AVHRR imagery, Russell-Smith et al. (2007) observed that 76% of total mean fire affected area (508 000 km2 p.a.) occurred in the northern savannas. Expressed as a proportion of continental land area defined by rainfall classes: a mean of 0.6% of southern Australia (53% of continental land area) was affected by fire each year; 5% of central Australia (25% of continent); and 23% of northern Australia (22% of continent). These general patterns are reflected also in updated (1997–2007) continental mapping of the frequency of large fires derived from AVHRR imagery (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2 Examples of fire mapping from the North Australia Fire Information website (www.firenorth. org.au): (a) an overview of the Top End region, (b) a subset of Kakadu and western Arnhem Land. Pink and red dots indicate fires in the previous 6 and 24 hours, respectively, with blue dots indicating fire locations over the preceding week. Coloured areas represent fire-affected areas mapped by month (see legend in the bottom right-hand corner of each map).

At a continental scale, fire extent is substantially explained by rainfall seasonality; that is the ratio of the amount of rainfall received in the wettest to driest quarter (Russell-Smith et al. 2007). In the monsoonal north, intense bursts of high summer rainfall, separated by an extended annual dry season (southern winter and spring) ‘drought’ – during which next to no rain may fall for 6 months or more – drive an annual cycle of elevated fire risk, alternating with periods of little or no fire risk. In the arid centre, erratically variable periods of above average rainfall and subsequent high rates of plant growth may alternate with dry periods extending over several years to decades. Susceptibility of landscapes to fire therefore changes over longer than annual cycles, but very large wildfires occur with some regularity: fuelled mostly by grassy fuels such as Spinifex. In parts of mesic southern Australia (especially forested regions), vulnerabilities increase with fuel accumulation over many years, so that when fires occur, mostly in summer, they can be extraordinarily intense.

Figure 1.3 Frequency of large fire-affected areas (>~2–4 km2) derived from AVHRR imagery, 1997–2007. North of the line indicates the tropical savannas region as defined by the Tropical Savannas Cooperative Research Centre.

For the tropical savannas (Figure 1.3), mean annual rainfall declines rapidly from more than 2000 mm in parts of the far north to about 500 mm in southern regions (Figure 1.4). The annual mean extent of large fires follows this general trend (Figure 1.5). Significantly, modelling of fire extent with a range of biophysical variables (e.g. antecedent rainfall, or fire, in previous year(s); or land use) suggests that rainfall is sufficiently reliable in the north to support annually recurrent burning (Russell-Smith et al. 2007). With declining, less-reliable annual rainfall, fire propagation relies on cumulative antecedent rainfall for the development of adequate fuel loads and fuel continuity (Allan and Southgate 2002; Meyer 2004).

A critical salient feature of contemporary savanna fire regimes concerns the predominance of fires occurring in the latter part of the dry season: typically under severe fire weather conditions (periodically strong south-easterly winds, high temperatures, low humidities and fully cured fuels). For example, of the annual mean 351 000 km2 of the tropical savannas region affected by large fires over the period 1997–2007 (Figure 1.3), 67% occurred in the late dry season months of August–November. Fire regimes dominated by frequent, large, late dry season fires are commonplace in many regions of northern Australia, especially the Kimberley region in the north-west, the Top End of the Northern Territory, and western Cape York Peninsul...