![]()

1

Agricultural ecosystems

If we say that agricultural crops are produced by ‘modern methods’, usually we mean that many of the same or similar variety of plants will be produced at the one time. ‘Sequential plantings’ of many vegetable crops means that there will be locally abundant amounts of a range of different aged plants within a region. This also means there will be an abundant to almost limitless supply of food for any pest that feeds on such a crop. More permanent crops, such as glasshouse roses, tree crops and vineyards, present similar situations, offering an abundance of food of the same type for much of the year, if not all year round.

This situation is not new, as farmers have always had to deal with pest problems. What changes are the availability and effectiveness of tools that can be used against pests. Farmers now have an array of synthetic and natural pesticides at their disposal, and can use products, usually insecticide sprays, that have become the basis for most pest management in horticultural crops in Australia and many other countries. Genetically modified crops are also now being used, and in some cases, such as cotton production in Australia, they have become the mainstay for the control of key pests in that industry. Commercially produced beneficial species are also available to counter certain pests.

The use of synthetic insecticides has brought with it its own set of problems, including residues in produce, non-target mortality, secondary pests and insecticide resistance. To counter such problems there have been further developments in pesticide production and in spray management techniques. As will be seen later in the book, some approaches (such as Insecticide Resistance Management strategies) probably have led to on-going problems in pest management while dealing with short-term crises.

Figure 1.1 A boom spray in action

Before modern pesticides and fertilisers

So what did farmers do before the advent of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers, and how do some farmers manage to do without them (or with extremely little use) in highly valuable horticultural crops? The approach to dealing with pests, diseases and soil fertility changed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when chemical options became widely available. Until then farmers did not have the apparently cheap and easy option of applying chemical products with impressive results. Instead they relied on rotation of crops and the application of composts and mulches: it was necessary for farmers to rotate different crops or pasture carefully on the same paddock. That prevented the build-up of soil-borne diseases, weeds or pests that might affect any one crop type, as the problems could not survive well without a suitable host. Green manure crops and composts have been essential to maintain soil fertility for centuries.

What lives in a crop?

What lives in a crop? Although a monoculture may be grown, it is not the only species living in the paddock. There are micro-organisms (bacteria, fungi, nematodes and protozoa) present in all soil: these account for more than all the other life present in terms of biodiversity and sometimes also as biomass. These are beyond the scope of this book, except where some are involved as pests or in pest control.

At a slightly higher level in terms of size are the micro-invertebrates: organisms that can only be seen with a microscope. These include some tiny insects and mites, and also insect-like organisms such as springtails. Some of these are pests, some are beneficial in terms of controlling pests, and others are benign, including many species that would contribute to the process of nutrient cycling.

The amount that we know about the number of species of both micro-organisms and micro-invertebrates is very small. Estimates of how many species have been described have recently been estimated using DNA extraction techniques. The results were surprisingly low. Our knowledge of both micro-invertebrates and macro-invertebrates in Australia is far less than in some other parts of the world because of what has been referred to as the ‘taxonomic impediment’: the relatively large proportion of the Australian invertebrate fauna that is undescribed scientifically. It is extremely difficult for scientists to begin studying individual species or build up the knowledge about particular species because of the lack of information published about them. The situation is different in places such as the UK or Europe, where naturalists and scientists have been observing insects, for example, for centuries, and so a large body of information has been accumulated.

In Australian agricultural ecosystems, of the micro-invertebrates affected by agricultural practices, some will be provided with a more suitable environment while others will be disadvantaged. The impact of pesticides, particularly those applied to the soil, will obviously have great potential to change the species composition of micro-invertebrates in any given patch of soil. However, factors such as tillage, irrigation and rotation can also have massive impacts on the soil fauna.

The macro-invertebrates are larger in size and may be defined as being able to be seen without a microscope, or more commonly, can be seen with just the naked eye. Because they are more easily seen we know more about these invertebrates than the smaller species, but still there is much that remains unknown. While more of the larger species have been given scientific names than the tiny ones, that is the limit of our knowledge for many Australian species. Information such as life-cycle duration and ecology, including feeding preferences, are mostly lacking. However, just because we cannot see something does not mean it is not there. Just because organisms do not have a scientific name does not mean that they are not there or cannot function as a biological control agent. Entomologists have long known this, and have conducted experiments called ‘predator exclusion trials’. This often involves spraying an insecticide that is broad spectrum and would kill predatory species. Pest species in blocks treated in this way can be compared to untreated blocks and an estimate of the impact of even unknown predatory species can be made.

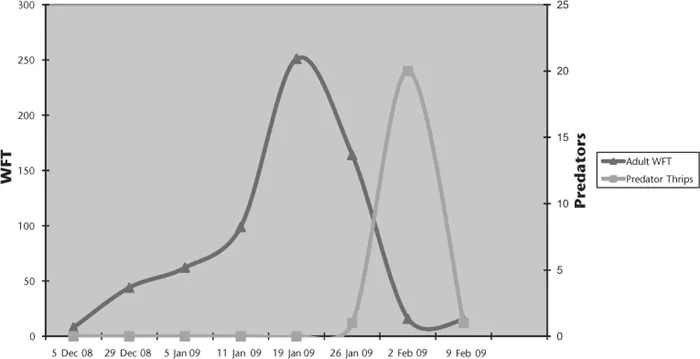

Predator–prey cycle

In pest management a key concept is the predator–prey cycle (see Figures 1.3, 1.4 and 3.1). When numbers of prey (in this case the pest species) are low then numbers of predators that eat them are also low. However, as prey (pest) numbers increase, there is a correspondingly larger food supply for the predators, so the numbers of predators can increase. The larger numbers of predators have an impact on the size of the prey (pest) population and numbers begin to fall. This is the desired result in pest management. The consequence of a smaller supply of prey means that eventually the size of the predator population also begins to drop.

This type of cycle is known to occur with many different types of animals, including lynx and hare, foxes and rabbits. The one given here is western flower thrips and a predatory thrips from strawberry crops in Victoria, Australia. The main difference between these examples is the time that it takes for populations to respond. With mites it is weeks or even days, but for foxes and rabbits it may be months or years that it takes for the populations of each to have an effect on the other.

Figure 1.2 Tubular black thrips, a predator of thrips and mites. (Photo by Denis Crawford, Graphic Science)

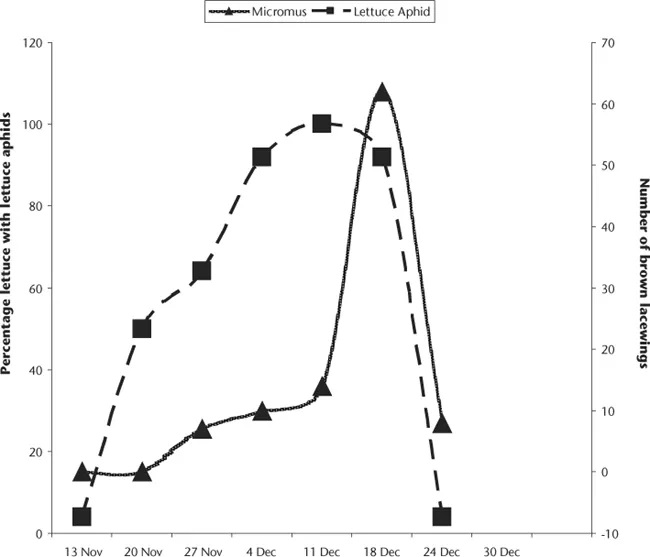

A second example from our data is control of lettuce aphid in lettuce crops in Victoria, Australia, this time by the predatory brown lacewing (Figure 1.3). Lettuce crops at this time of year in Victoria take about 8 weeks from seedling transplant until harvest. Lettuce aphid is a pest that is tolerant of many insecticides, but also is extremely difficult to target within head lettuce (such as ‘iceberg’), because it is protected from direct contact with insecticides because of the structure of the plant. The aphids live inside the heart of lettuces and are protected by overlapping leaves. The accepted method of dealing with the pest in Australia and New Zealand has been to drench the seedling plug in the nursery, just before planting in the field, with a high enough rate of the systemic insecticide Confidor to protect the plant from lettuce aphid for the life of the crop (until harvested).

This method requires a decision to be made, before the crop is planted into the paddock, as to whether or not the insecticide treatment is to be used. Some varieties of lettuce are resistant to lettuce aphid, but these are not always considered by growers to be as suitable as susceptible varieties. Biological control agents (such as brown lacewings, hoverflies and ladybird beetles) as part of an IPM strategy can deal very effectively with lettuce aphid. Commercial crops are grown successfully every year in Australia without insecticide drenches.

One problem is the short time that it takes to grow the crop; another is that the decision on control needs to be made before planting. If the decision is made to not use insecticide drenches on seedlings, it is made because (at the time) there were no insecticide sprays that would be effective. (This situation has since changed with the arrival on the market of Movento, which is a true systemic insecticide.) The short life of the crop is sometimes seen as being too short for biological control to work, because the predators do not arrive before their food source (lettuce aphid).

Figure 1.4 illustrates what we have seen happen in lettuce crops, but particularly the first planting when moving to a new paddock where no predators of lettuce aphid are already present. It shows how lettuce aphid arrives very soon after lettuce seedlings are planted, but there is a considerable lag before the predators of lettuce aphid (in this case brown lacewings) begin to increase and have an impact on the lettuce aphid population. However, once the brown lacewings begin to breed within the lettuce then the subsequent control of lettuce aphid, as measured by the extremely rapid drop in lettuce aphid level, is complete and achieved before the crop is harvested. Lettuce aphid is a problem as a contaminant rather than causing direct damage and so once the aphids are eaten there is no residual damage and as there is no food for the lacewings (or other predators) then they also leave in search of a new food source.

These two examples illustrate how effective biological control agents can be, but the worry for growers is the level of pests that is reached before control occurs, and trusting that control is in fact going to occur. For effective control, the height of the peak in numbers of pests (prey) should be tolerable until the numbers of predators build up to a level that will achieve control. The shape of the graph in both cases is the same: a peak of prey followed by a peak of predators, and then a drop in both.

Figure 1.3 Numbers of western flower thrips and predatory tubular black thrips (in strawberry crops, Victoria, Australia)

Figure 1.4 Lettuce aphid control by brown lacewings (Micromus)

Another example of this type of interaction that we often encounter is control of two-spotted mite by another mite called Persimilis. Two-spotted mite is a serious pest for many horticultural crops, including fruit (such as apples, pears and strawberries), flowers (roses and gerberas, including glasshouse and outdoor crops), nursery plants (ornamental horticulture) and some vegetables (such as beans, capsicums, cucumbers and eggplants), but it is often a major pest in glasshouse crops. This pest can cause serious damage by feeding on the cells of host plants, and if in high enough numbers, populations of the mite can defoliate plants. The foliage appears to have been burnt, because the cell contents are destroyed. When the pest populations are high they cover leaves, or what is left of them, with webbing, which gives rise to a commonly used name of spider-mite.

A problem for farmers trying to deal with two-spotted mite is that, in many cases, the pest is resistant to most of the miticides available. Although the newer miticides may work, if overused they fail because the short generation time of two-spotted mite (particularly in warm, dry conditions) allows resistance to develop very rapidly. However, as mentioned above, two-spotted mite has a specific predator, the mite called Persimilis, and it cannot rapidly develop resistance to this natural enemy.

Persimilis is more susceptible to pesticides (particularly insecticides and insecticide residues) than two-spotted mite. For example, a single application of some insecticides can kill Persimilis if it walks on treated leaves for 12 weeks or more after the original application in glasshouse crops. However, if there are no complicating factors as a result of pesticides, then Persimilis can be introduced, as it is commercially available. If two-spotted mite populations are large, they provide a large food source for Persimilis, so the predatory mites begin laying many eggs among the pests. At first the predators may be greatly outnumbered and the pest population will continue to grow. However, as each generation produces ever-increasing numbers of predators, they begin to have an impact on the pest population, which at first stops increasing in size, then begins decreasing. This lag between the initial introduction of the predator and the point of achieving control depends mainly on the starting size of the pest population and the number of Persimilis introduced. Factors such as temperature and humidity will influence the rate of population increase or decrease, but the relative number of pests and predators is the most important factor. When the population of two-spotted mite is controlled, then the Persimilis do not have a food source, so their ...