![]()

Chapter 1

Grain crops

The greatest challenge facing the settlers who arrived on the First Fleet in 1788 was to grow enough food for themselves. Their initial sowings on the sandstone soils in what is now the centre of Sydney were a disaster, so cropping was moved to more fertile land at the head of the harbour (Parramatta) and then to the even more productive Hawkesbury/Nepean River Valley.1 But this took time, as did learning to farm in a new land. Supplies were slow to arrive from home and the infant settlement was often hungry in its first five years.2

The problem was that wheat did not grow very well in coastal New South Wales.3 Maize did better, but the colonists did not like eating grits and cornbread and persisted with wheat. While they were able to grow enough of it to meet their needs in good years from about 1795 onwards, they had to import or go short when harvests were poor. Supplies improved when Tasmania and then South Australia began to export, but New South Wales itself was not consistently self-sufficient in wheat until the end of the 19th century.

This chapter tells the story of how Australia developed grain growing and became one of the world’s leading wheat exporters. But first, it is instructive to look at the food and farming practices that the British and Irish brought with them to Australia. These inherited practices were most influential during the first half-century of settlement. By the 1840s, the colonial farmers had begun to make their own inventions, such as the stripper-harvester, and to look to other new European-settled countries such as the United States for ideas rather than to Europe itself. There had, of course, been a lot of improvisation from the start, because conditions were so very different from those at home.

The colonial inheritance

Food preferences

At the time of settlement, many people in the British Isles still lived on the lesser grains, depending on incomes and relative prices,4 and there were distinct regional patterns of consumption too. Wheat was most important in the south and east of England, barley and oats in the north and west of England,5 Wales, Scotland and Ulster. Rye, the hardiest of all the cereals, had faded out of use during the 18th century; formerly it had been grown on the poorest soils and in the coldest parts of the kingdom.

In fact, Britain was in the process of switching to wheat. The equivalent of about 66 per cent of the population of England and Wales probably ate wheat in 1800, and 88 per cent in 1850. In Scotland, the percentage of wheat eaters rose from 10 to 44 per cent over this half century, while that of oat eaters declined from 72 to 50 per cent.6 So wheat was in the ascendancy at home and it was the clear preference in New South Wales too.

Approximately 6–8 bushels of corn (cereal grain) were available per person per year in England between 1788 and 1850, with little evidence of any time trend.7 That is equivalent to about a pound (about half a kilogram) of wheaten flour per person per day. A similar quantity of flour or bread was issued to all adult males after their arrival in New South Wales.8 Australians were eating only about half as much as that in the 1990s.

Peas (the pease pudding of the old nursery rhyme) made an important contribution to the protein content of diets in the United Kingdom at the time of settlement. The marines on the First Fleet were issued with two pints of them a week and they were initially part of the ration at Sydney Cove. Faba or broad beans were not so highly regarded; the prevailing opinion of the period was that they were a flatulent and coarse food better suited to the laborious than the sedentary class of society.9 Accordingly, they were fed mostly to horses, swine and other livestock.

Supplies of cereals

Two aspects are of particular interest in relation to what happened in Australia: Britain’s achievement in remaining largely self-sufficient in cereal production until the 1840s and then the creation of an open market in which colonial exports had to compete with those from the rest of the world. The British population roughly trebled between 1750 and 1850, yet for most of the time the country was able to get by with only modest imports of foreign grain. How this was done is described in more detail under the next heading. Many observers thought that the same methods should have been used in Australia, but they were not, and for good reason.

The Irish situation was even less relevant to the early development of Australian grain growing. Ireland produced ‘far more grain than might be expected in competitive conditions from a country with such a damp climate’10 and in the mid-1830s supplied as much as 80 per cent of Britain’s closely regulated wheat imports. However, this was largely an artefact of the protection afforded by the Corn Laws under the special relationship formalised by the Union of 1801. Meanwhile, more and more potatoes were being grown and eaten in Ireland (see Chapter 7).

The second point relates to what happened after the Corn Laws had been repealed in 1846. The United Kingdom then espoused free trade and continued to do so until after the first of the two World Wars that dominated the 20th century (1914–18 and 1939–45). What this meant was that when Australia began to ship wheat home on a regular basis in the 1870s, it was fully exposed to the harsh discipline of global competition. In fact, the competition was so intense that British arable agriculture collapsed under the pressure, although Australian grain played virtually no part in that collapse.

Farming practices

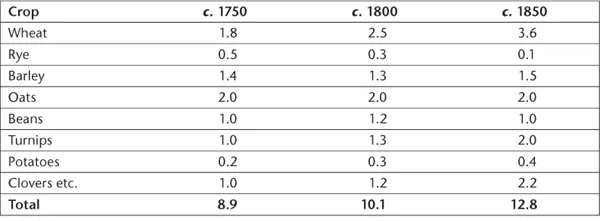

Production of the four main cereals probably doubled in England and Wales over the century from 1750 to 1850, and much of the increase was due to higher yields, with the total area of these crops expanding only by about a quarter (Table 1.1). While some British historians have labelled these changes as an ‘agricultural revolution’, they do not really fit the criteria defined by those who have studied industrial revolutions in general, such as the substitution of mechanical for human effort, of inanimate for animal power, and of new and more abundant raw materials for old ones.11 In the case of British agriculture, it was more a matter of implementing a useful innovation that had been around for some time: the practice of rotating fodder crops with grain crops.12

Table 1.1 Estimated areas of the chief crops of England and Wales, 1750–1850 (millions of acres)

Source: Holderness, B. A. (1989). In ‘The Agrarian History of England and Wales Vol. 6: 1750–1850’. (Ed G. E. Mingay.) table 2.7. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.)

Although British farmers had long been producing both crops and livestock, they had usually managed them as discrete components of their operations. The grain crops had typically been grown in a two crops followed by a fallow sequence on the arable land while the rest had remained under permanent pasture. But well before Australia was settled this old separation had begun to break down under the influence of fodder crop rotations. The Norfolk four-course sequence (wheat, turnips, barley, and red clover) was the best known of these; it substituted fodder crops (turnips and clover) for bare or weedy fallow, and alternated fodder and grain crops on the arable fields. The feed supply for livestock was greatly improved and soil fertility was enhanced by the nitrogen that the legumes fixed from the air.13 The root crops were partly grazed in situ (often by sheep), and partly conserved for winter feed, while the legumes were usually made into hay before the aftermath was grazed. Plant nutrients were recycled by fertilising the fields with the farmyard manure that had accumulated in the yards and buildings where the stock had over-wintered. The whole system was called ‘high farming’.

These fodder crop rotations were not a British invention; they had evolved on the continent in earlier times, and had been perfected in Flanders and Brabant, that is, in present-day Belgium and the adjoining regions of the Netherlands and France.14 When first introduced to England, they were practised in Norfolk (hence the name) and their adoption is reflected in the rising acreages of turnips and clovers in Table 1.1. However, a number of modifications were made to the classical four courses in the process:

• Other fodder crops were planted instead of turnips and red clover. By 1850, the list of root crops included swedes, fodder beets and potatoes, while rape, cabbages and kale were also being grown for feed.15 Lucerne, sainfoin, and white clover/ryegrass were the principal alternatives to red clover. These changes had been necessary because of the build-up of pests and diseases that occurred when turnips and red clover were replanted as often as once every four years.

• The sequence was extended beyond four courses. As soil fertility improved, more than one cereal crop could be taken before the next fodder crop was sown, while the proportion of fodder crops could be expanded if livestock prices were high enough relative to those for grain. In the East Lothian region of southern Scotland, for instance, the proportion of ley ranged from 50 per cent of total arable in 1780, when wheat prices were quite low, to 16 per cent in 1812, when they were high.16 (A ley is a pasture that is sown with ...