![]()

PART I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

CHAPTER 1

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF VIROID DISEASES

J.W. Randles

Viroids are pathogens of food, industrial and ornamental plants. An evaluation of their economic impact faces the same difficulties as encountered for other obligate intracellular biotrophs, such as viruses, phytoplasmas and fastidious bacteria. Viroid diseases are inconspicuous compared with diseases caused by fungi, bacteria and nematodes, and losses identified in comparative trials on their effects do not necessarily translate to global estimates of loss. Their effects also extend beyond direct effects on yield and quality. The range of direct and indirect damage associated with plant virus infection (Waterworth and Hadidi 1998) largely applies also to viroids.

This chapter attempts to consider viroids as one of the many factors that affect world agriculture. It therefore commences with an outline of the history of agricultural development, world food needs and the availability of land. It discusses the role of crop protection. The deployment of new technologies in crop protection and their role in discovering viroids is a precursor to discussing the economic impact of viroids by referring to specific case studies. Crop damage caused by viroids, potential benefits of viroids, and their mode of spread are considered before considering the need for, and the design of appropriate control measures.

FORECAST OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND LAND REQUIREMENTS UNTIL 2150

The epoch of science and industrialization is considered to be the 300-year period from 1850 to 2150, in which the world population will show a logistic increase (Weber 1994). Economic divisions between countries with rural and industrial economies can be expected to remain for most of this era. Patterns of population growth for developing countries will be logistic, with an associated demand for greater quantities of food. In contrast, industrialized countries will show a minor increase in population and an associated demand for improved quality of food and lifestyle. It is estimated that the current world population will double to a peak of about 12 × 109 in the next 120–150 years, a limit imposed by the consumption of more resources and pollution by industrial and agricultural wastes rather than an inability to expand food production. The individual mean energy requirement of food is about 3000 cal per day, and the projected doubling of the world population, together with an increased demand for quality, will require research and development of new products and processes, as well as world peace and international support for poorer countries (Weber 1994). Up to 3 × 109 ha of land could be cultivated worldwide and, with improvements in agriculture, should be adequate for the expected limit of world population. However, the cost will be further clearance of natural vegetation with associated deleterious effects on ecosystems and loss of biodiversity.

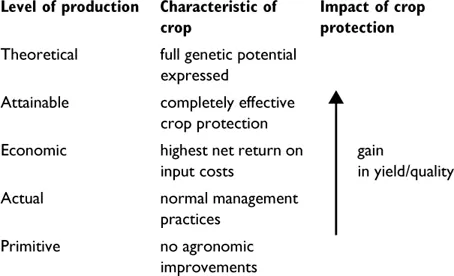

Figure 1.1 The impact of crop protection on crop production. The ‘actual’ level achievable at a site where normal practices are used is compared with the level ‘attainable’ when all pests are absent. The impact of crop protection falls within the range indicated by the arrow (based on Oerke et al. 1994).

Land-saving advances in technology contributing to improvements in food production will continue to be the use of chemical fertilizers, plant breeding and crop protection. Of these, crop protection is the most complex because of the range of crops, range of pests, pathogens and weeds, and the different life cycles of each of these. Also, the need for crop protection increases with increases in crop yield because of the higher plant density, shortened intercrop periods, monocultures, and the increased use of fertilizers and irrigation. An essential component of crop protection in the future will be the generation of information through research and the use of this information for control of crop losses.

CROP LOSSES AND CROP PROTECTION

Theoretical levels of crop production are summarized in Figure 1.1. Crop loss can be defined as the difference between actual yield under normal optimum agronomic conditions and the yield attainable for the same crop with completely effective crop protection. The effect of crop protection is a gain in yield or quality. Economic yield is the level at which incremental costs of crop protection reach but do not exceed the incremental increase in value of the crop. Ideally, estimates of loss would be a prerequisite for the rational development of plant protection programs, but crop loss assessment is complex and inexact (Oerke 1994). An estimated global figure for preharvest crop loss from all sources is considered to be about 40%, while post-harvest losses are estimated to be in the range of 10–50%. Thus, more than 50% of produce grown is lost before reaching the consumer.

In plant pathology, research has provided better diagnostic methods, more accurate information on epidemiology, disease forecasting, cultural control measures and novel forms of resistance. Integrated crop management combines these with other strategies as a basis for sustainable agriculture, including concern for natural resources and represents a logical way forward between the extremes of ultra-intensive agrosystems and low output organic farming (Dehne and Schonbeck 1994). Because of high costs and the need for research infrastructure, these measures are first adopted by developed countries. Developing countries may only invest in selected techniques for use in crops destined for export to countries which impose strict tolerances on food quality or plant health.

THE DEPLOYMENT OF NEW TECHNOLOGIES IN PLANT PATHOLOGY

The range of techniques available does not provide an adequate solution to all disease losses. Where therapeutic means of control are not available, as for the intracellular biotrophic pathogens, indirect control measures are needed, but they can only be applied if the disease cycle is known. Such solutions are often temporary and require continued intellectual input to remain relevant to the requirement for sustainability. Biotechnology and genetic engineering are the most recent contributors to new control strategies. Direct incorporation of resistance genes against many plant viruses by transformation of plants with pathogen-derived nucleotide sequences is now well tested and the phenomenon of gene silencing is now under intensive study (Hull 2002). Moreover, the development of highly sensitive and specific nucleic acid based diagnostic tests promises to revolutionize quarantine practice and pathogen-testing schemes for exclusion of infected plant material. The cost effectiveness of this technology is now widely recognized and it only remains for it to be deployed where it is likely to be most effective.

Research on viroids over the last 30 years has paralleled and contributed to the development of biotechnology. The discovery of the first viroid, Potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd), exemplifies the ground-breaking consequences of identifying a new paradigm in plant biochemistry and pathology. The positive economic impact of the original discoveries that previously enigmatic diseases were due to viroids has been greatly multiplied not only by the ability of workers in quarantine and pathogen-testing schemes to identify, evaluate and control viroids, but by their ongoing contribution to understanding cellular processes in molecular biology and particularly the puzzle of how they produce disease. This positive economic impact is highly significant but impossible to quantify because many of the long-term consequences are not obvious.

LOSSES DUE TO VIROIDS

Viroids vary in the hosts they infect, the type and severity of disease that they cause, their mode of spread and their epidemiology. They also vary in pathogenicity, time to induce disease, interactions with other pathogens and response to the environment. Control measures may be available for some, while the lack of knowledge of the epidemiology may prevent the formulation of reliable control strategies for others. Many of the known viroids were discovered because they induced serious damage to their host crops. Following their characterization, attempts were made to monitor their incidence and effects. This was intended to lead to quantification of the dynamics of incidence, spread and distribution, followed by the prediction of outbreaks and the deployment of control treatments.

As each viroid has a unique disease cycle, each disease cycle needs to be defined so that a specific system of assessment, loss prediction and control can be established. The measurement of losses due to viroids has two aspects. The first is the severity of the disease induced by infection with the viroid and its variants. The second is the prevalence of the viroid and its ability to spread and produce an epidemic. Direct losses can be measured either as a depression in yield or as a cash loss. These losses will vary with the viroid, the crop, time and the environment. The types of loss that have been reported from viroid infection include losses of whole plants, damage to parts of plants, damage to plant products, damage to subsequent generations, and the effects of coinfection with other endoparasitic pathogens.

Whole plant losses

The effect of lethal viroid diseases of coconut palm such as cadang-cadang and tinangaja, as well as those leading to the removal of unproductive annual or perennial plants, can be evaluated using a descriptive formula:

Loss = value of plant

+ cost of replacement

+ time lost from interrupted production

+ cost of diagnosis

This implies that where viroid control is achieved by eradication and replanting, the effect on loss will be the same as natural death of the plant. This situation allows individual losses to be calculated with reasonable accuracy.

Damage to parts of plants

Specific tissues and organs of plants may be directly affected, or a general reduction in growth rate may cause stunting and reduced yield. For example, foliage may be distorted, chlorotic or damaged through increased susceptibility to sun or wind. Plant structure may be affected by reduced growth, lesions on the stem or reduced translocation of water and nutrients. Reproductive structures may be affected. For example, flower production may cease, or flowers may show necrosis, reduced size or change in pigmentation. Fruit may be altered in size, shape, quality, color or markings. Seed may be small or shrivelled, with changed composition or viability.

Meristems, at both apex and root tips, may show reduced cell division, altered patterns of differentiation leading to hypoplasia or hyperplasia in plant tissues. Any reduction in cell division will be a precursor of reduced growth rate in both roots and tops of plants. This may be reflected in shortened internodes or loss of apical dominance in dicotyledonous plants, or ‘pencilling’ of the trunks of monocotyledons such as palms. These reduced outputs by the plant occur despite normal inputs of labor, nutrients and water.

Damage to plant products

If the economic product of the plant is a tuber, nut or fruit, downgrading of quality, predisposition to damage at harvesting or in storage, and reduced yield at harvest, may be components of loss. Seed viability, strength of the plant’s framework and of timber harvested from the plant may be reduced by viroid infection and incur a cost. Variation in growth rates of infected compared with viroid-free plants may incur labor costs in plantation management, as for hops with reduced extension of bines when infected with Hop stunt viroid (HSVd).

Effects on subsequent generations

If a viroid is transferred to the next generation of the host species, in true seed or vegetative propagules, the rate of transmission and the cost of an epidemic resulting from secondary spread from these primary sources of infection will determine the extent of future losses.

Mixed infections

A range of consequences may arise from mixed infection either with different strains of viroids, with different viroids or with viroids and viruses (Garnsey and Randles 1987).

Cross-protection occurs between mild and severe isolates of several viroids. It has not been used as a control measure for viroids, but has been used to identify mild strains of PSTVd in biological indexing programs. Molecular analysis has indicated that for viroid-infected perennial crops such as grapevine, stonefruit and citrus, a most important consequence of mixed infection is the appearance of recombinant ‘new’ viroids, with the potential for genetic properties to be derived from several co-infecting viroids. Synergism has been reported in potato between PSTVd and Potato virus Y (Singh 1982). The report (Francki et al. 1986) that PSTVd could be encapsidated in Velvet tobacco mottle virus, which is mirid transmitted in nature, indicated that co-infection may have major consequences for viroid epidemiology by providing an unexpected mode of spread. Salazar et al. (1995) reported very high rates of t...