![]()

CHAPTER 1.

What is biodiversity, and why is it important?

Steve Morton and Rosemary Hill

| Key messages |

| * | Biodiversity is the term used to encompass the variety of all living organisms on Earth, including their genetic diversity, species diversity and the diversity of marine, terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, together with their associated evolutionary and ecological processes. |

| * | Biodiversity makes human life on Earth possible yet it goes beyond mere measurable scientific facts; understanding biodiversity highlights the benefits of the natural world, many of which are at risk due to the pressures of human resource-use. |

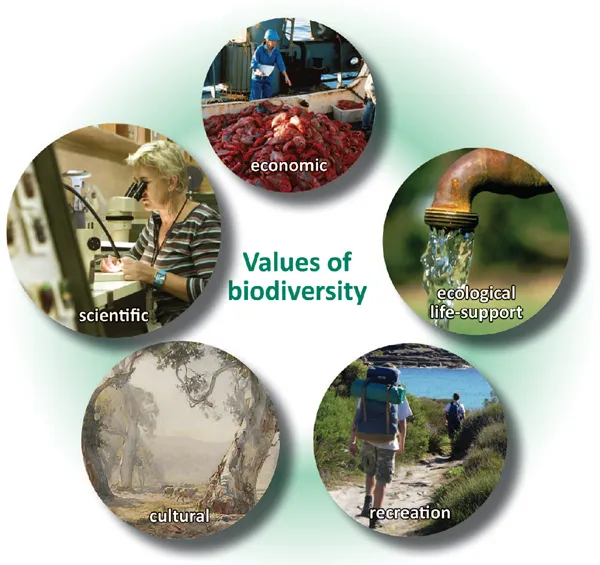

| * | Biodiversity is a human construct reflecting various values – economics, ecological life-support, recreation, culture and science – placed upon it according to perceived benefits and risks. |

| * | This book focuses on options for improving the management of Australia’s biodiversity in response to such societal values. |

WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?

A writhing mass of Murray crays is revealed as the drum-net emerges pull by pull from the river, the greenish water draining in pulses from its mesh. The boy watches with keen anticipation as his father strains at a length of fencing wire attached to the net. There are such numbers of crayfish that they crawl in confusion over each other and around the sodden sheep’s head that acts as bait. His father unlatches the door of the net and carefully extracts the animals, avoiding harm to his fingers by grasping the body behind the dangerous fore-claws. If eggs of deep crimson are found on the under-tail of a female, she is tossed back into the water, as are young individuals. The boy helps his father carry the wriggling hessian bag containing the catch a hundred metres or so to the homestead. They walk in the shade of the stately, heavy-limbed river red-gums that line the stream, the foliage glowing green and bronze in the late afternoon sun. The boy could hardly be happier.

The Murray River and its river red-gums, Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Photo: Matt Colloff, CSIRO.

In the laundry the copper is quickly lit and, as soon as its water is boiling, the crays are dropped in to cook. Only a short time is required before they can be lifted out, their original muddy green colours turned to a rosy blush. Father and son sit on the verandah while breaking up the crays and placing the chunky flesh from the fore-claws and tails into a bowl for the family’s evening meal. They suck the juicy slivers of meat from the slim hind-claws and scoop out and eat the fatty deposits lining the carapaces. The flavours are deliciously sweet and subtle, a delicacy of taste never to be bettered in the boy’s subsequent life. Now he is at a peak of delight, deeply at home in an Australian paradise.

The Murray crayfish, Euastacus armatus. Photo: Rob McCormack.

Most of us hold on to some vision of an idyllic, productive or beautiful environment, often imbibed unconsciously in childhood and youth. The man grown from the boy – he is in fact one of the present authors – still admires most of all the Riverina plains country with its splendid river red-gums. Each of us has our own vision, though, not necessarily shared with others. We form a sense of the environmental values of our own particular place, not only as we come to maturity but throughout our lives. These values are at the heart of the concept of biodiversity, a notion that is only partly about science because it is based also in emotional experience and culture. First and foremost, appreciation of biodiversity springs directly from human interaction with the natural world. Often these experiences involve immediate use of the environment, such as working on the land or harvesting its bounty (especially its Murray crays!). Frequently, too, they stem from a simple enjoyment of the natural world through beach-going or bushwalking. Whatever the details of the individual human experience, the idea of biodiversity cannot be fully understood without the recognition of its roots in a perception of environmental values.

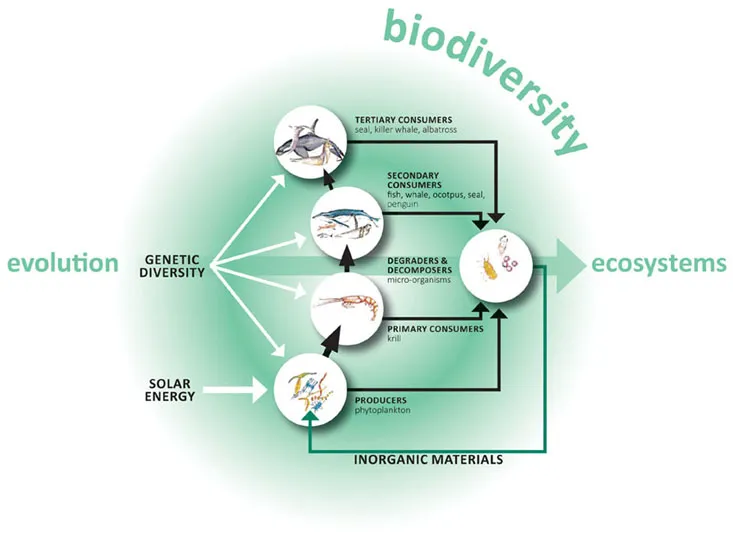

Biodiversity does encompass a significant component of scientific inquiry, of course. Scientists define biodiversity as the variety of all living organisms on Earth and at all levels of organisation (Figure 1.1). It incorporates living things from all parts of the globe, including land, sea and fresh waters. It constitutes all forms of life – bacteria, viruses, plants, fungi, invertebrate animals, animals with backbones – and not just the things we can see or prey upon. Biodiversity includes human beings too. Yet the scientific definition of biodiversity includes more than just organisms themselves. Its definition includes the diversity of the genetic material within each species and the diversity of ecosystems that those species make up, as well as the ecological and evolutionary processes that keep them functioning and adapting. Biodiversity is not simply a list of species, therefore. It includes the genetic and functional operations that keep the living world working, so emphasising inter-dependence of the elements of nature.

Scientists are striving to describe and measure the full variety of life, a massive undertaking when we consider the estimated nine million species on Earth, their genetic diversity, and the vast variety of ecosystems that they make up.1 What is more, science aims not only to understand the evolution of this kaleidoscope of life but also the ebb and flow of biodiversity through time in response to the inevitable natural disturbances and human-induced disturbances.3 Science is charged with the responsibility of providing us with the knowledge and evidence needed to meet our diverse expectations for the use and conservation of biodiversity.

Figure 1.1: Biodiversity is the web of life. This pictorial representation begins on the left with the evolutionary processes giving rise to the genetic diversity of living organisms, showing the organisation of the species carrying genetic diversity into food chains of producers (driven by energy from the sun), consumers and decomposers, and the ecosystems that the organisms make up. The diagram depicts a marine food chain. Redrawn from Biology: An Australian Focus.2

So it is that biodiversity is both a subject of scientific interest and a fascinating social construction. The term ‘biodiversity’ emerged in the 1980s from the conservation movement as a means of emphasising the values of the natural world under the pressure of human-induced environmental change and resource use. The concept underpinned the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992, as well as considerable activity by governments to try to balance the benefits and risks associated with loss of biodiversity. Behind the term is a shared concern about the future of the planet and the accelerating expansion of humanity’s effects upon the global environment. Further, the concept refers to more than measurable scientific facts or fears about risks associated with its loss. People throughout the world, many of whom may never use the term ‘biodiversity’, appreciate plants, animals, landscapes and seascapes for their usefulness and for qualities such as their spiritual significance – and it is because of these values also that biodiversity matters to us as human beings.

VALUES – WHY BIODIVERSITY MATTERS

Values are the lasting beliefs or ideals that will influence a person’s attitude and which serve as broad guidelines for that person’s behaviour. Values and value systems identifying what is good or bad, desirable or undesirable, are frequently shared by the members of a culture, even when not consciously expressed. Some values can be expressed in monetary terms so as to allow calculation of a common measure of worth. Yet, economic benefit provides only a partial measure of the full worth of things. Understanding biodiversity, and why it matters, is assisted by comprehending the range of distinctive values that individuals and societies may assign to the living world and the ecosystems that it comprises. It is an indication in itself of the complexity of views about biodiversity, and the variety of interactions with it, that at least five separate categories are necessary to cover all possibilities (Figure 1.2). They are described below, noting numerous possibilities for interaction among them.4

Figure 1.2: The five primary values of biodiversity. Photos clockwise from top: CSIRO; Willem van Aken; Chris McKay; Hans Heysen (Germany; Australia; France, b.1877, d.1968), Summer, 1909, pencil, watercolour on ivory wove paper, 56.5 × 78.4 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), purchased 1909, Photo: AGNSW, © C Heysen; David McClenaghan.

The first category has already been mentioned – economic. The natural world provides humans with raw materials for direct consumption and production, and from which to make money. We harvest fish and timber, for example, and make from them food and goods with utilitarian value in the marketplace. This category expresses the material use of nature by humans for direct benefit. These benefits – and the economic value system that lies behind them – are held especially dear by many whose livelihoods bring them close to the natural world, such as farmers, fishers, timber workers, bee-keepers, and so on.

A second value system comprises ecological life-support. Biodiversity provides humans with the healthy, functioning ecosystems that make up the Earth, without which our societies could not exist. Nature delivers to us a supply of oxygen, clean water, pollination of plants, pest control, and so on. As understanding and evidence about the interconnectedness of the natural and human worlds has grown over the past century, many have come to believe that protection of the web of life is vital to our own interests, and biodiversity is a convenient expression of that value system. In fact, the concept of ‘ecosystem services’ – the multitude of resources and processes that are supplied by biodiversity to human beings – grows out of this value. Such a value system is shared by almost all human beings in at least some degree.

The natural world’s opportunities for human recreation comprise the third set of values. The benefits of rejuvenation for those who hold to these values may be obtained from a tough bushwalk in Tasmania, a relaxed experience of bird-watching in the back paddock, or jogging beside a river in an urban setting. Tourism frequently gains commercial benefit from biodiversity as a result of international perceptions that in Australia these values are unusually prominent. Many Australians from all walks of life respond to them.

Next, biodiversity provides cultural values via the expression of identity or through spirituality or an aesthetic appreciation. The celebration in our National Anthem that ‘our land abounds in nature’s gifts of beauty rich and rare’ reflects an attachment to bio...