![]()

wild

Part one

plants

![]()

Common names

Names act as a highly effective shorthand for the objects around us, especially those items that we use regularly or regard as important. Try explaining to someone what happened in a room of 30 people without using the names of the people!

Hunter–gatherers know the plants on which they depend for food, medicine, clothing and tools, but with settled agriculture the world has become progressively urbanised. We are distanced physically and psychologically from the natural environment so that our experience of plant names may be poorer than it has been for generations. Most people know the names of only a few trees, common garden and food plants, and some weeds. A wide-ranging knowledge of plants is very unusual, perhaps only found in some professional horticulturists, keen gardeners, naturalists and botanists. In contrast, many of us are familiar with a range of technical terms used for the parts and functioning of our computers, cars and televisions, simply because we are so directly dependent on them.

Structure

Plant common names have a similar form in most cultures. They are generally composed of one or two words that reflect some aspect of the plant such as its appearance, origin or use. We often name and group objects including ourselves using a noun–adjective binomial, which is a name consisting of two words, one being the name of an object, the other a short description of that object. So, we speak of classes of objects like rice, roses, wattles and Pythons, and within each class particular individuals might be named; for example, Basmati rice, standard rose, Golden Wattle and Monty Python.

Origin

We assume that most common names were not imposed on people but arose when the need for a name occurred, and they were then maintained through common usage via the direct experience of the plants in nature or gardens, or by word of mouth. Nowadays, we tend to look up the common names of plants in books, except when they are familiar and widely grown garden or food plants.

In Australia, we have adopted many common names that are used in other countries, especially Britain and the United States. These common names used for introduced plants, names like elm, oak, pine and rose, originated long ago in Europe or Asia. The names of some Australian plants, such as Mulga, Wilga, Gungurru and Bangalow Palm (Figure 2) are taken from local Aboriginal languages. Others have names given by the early settlers and refer to their striking appearance, for example Kangaroo Paw and Grass-tree, or they were named for their similarity to European cultivated plants like Native Fuchsia and Willow Myrtle. Trees were sometimes given the names of other trees with similar timber, such as Silky Oak and Mountain Ash.

Common names are still being introduced. One exciting new development in Australia is the acceptance of Asian herb, fruit and vegetable names (often as English translations or transliterations) into our common name repertoire; for example, Vietnamese Hotmint, Pak Choi, and Star Fruit.

Figure 2: Archontophoenix cunninghamiana, Bangalow Palm Image: Rob Cross

Common names as an alternative to botanical names

For many practical people the Latin system of naming plants appears archaic. Latin is a complicated, unfamiliar and dead language. Latin names also seem to have little relevance to commercial realities. Are they really necessary in the context of, say, a retail nursery? After all, they can be even more confronting to customers than they are to nursery workers, and that does not help sales.

For these reasons it is sometimes suggested that we abandon the unfamiliar Latin and instead use the much simpler common names. In principle, this sounds like a good idea but on closer inspection there are several problems:

- Often there are many different common names for the same plant, and the same name may be used for different plants. Perhaps the commonest of common English names is Lily, which is part of the common name of well over 200 different kinds of plants, and this is followed by names like pea, bean, grass and palm.

- The common name favoured for a particular plant may change over time.

- Most importantly, although we might think we have a grasp of common name usage it is difficult to monitor precisely where and how much a particular common name is being used: common names differ, not only between countries, but also within a particular country, and even from one local area and community to another.

- When a single species is split into two new ones, should both still retain the common name? If ‘yes’, then how do we distinguish them by the common name? If ‘no’, then do we invent a new common name? And what happens when Baeckea behrii, Broom Baeckea, is transferred to the genus Babingtonia?

Botanical names are a way of grouping botanically related plants into families, genera, species and so on. Common names may also be used in this way so we have, for example, brassicas, eucalypts and Thunberg’s gardenia, which are the common name equivalents for plants in the botanical categories Brassicaceae, Eucalyptus and Gardenia thunbergii. However, common names may classify plants in all sorts of non-botanical ways, so they may just as easily give a false impression of plant relationships. The Australian Native Honeysuckle (Eremophila alternifolia or Lambertia multiflora or, sometimes, Banksia), She-oak (Casuarina), and Native Fuchsia (Eremophila or Correa), for instance, are botanically unrelated to their exotic namesakes Honeysuckle (Lonicera), Oak (Quercus) and Fuchsia. The common name Mint is based on a plant’s smell and flavour, and therefore does not always apply to plants in the genus Mentha, the culinary mint genus. We categorise food plants into vegetables and fruits, and garden plants by their garden function as a windbreak, groundcover or climber. Eggs-and-bacon is a name given to almost any Australian native plant with red and yellow pea-like flowers; although all these plants are in the botanical family Fabaceae, it is the red and yellow colouring that is an equally important factor in determining the common name.

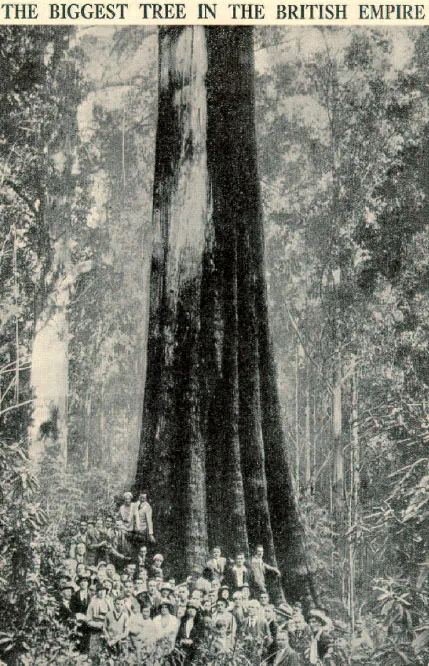

The following example illustrates the difficulties associated with using the popular common name Mountain Ash. The Mountain Ash of the Australian state of Victoria, Eucalyptus regnans (Figure 3), is so called because its timber resembles that of the European Ash, Fraxinus excelsior. In Tasmania, it is known as the Swamp Gum, a name that in Victoria is generally given to Eucalyptus ovata. In England, the Mountain Ash is a small upland tree with ash-like leaves and red berries, Sorbus aucuparia, which in Scotland is called Rowan. In America, the Mountain Ash is Sorbus americana. You see the problem!

The Cultivated Plant Code deals with the hotch-potch of different kinds of common names by distinguishing between: colloquial names, those used in local communities but not widely enough to be recorded; common names, the non-scientific names widely used and recorded in a particular area; and vernacular names, those translated from scientific names into the local language.

Latin botanical names overcome all this confusion because there is only one botanical name for each kind of plant, even though that name might change from time to time! The principle of one name for one kind of plant is universally appealing and important regardless of whether the names we are using are commercial, legal or scientific. With modern marketing, a nursery worker will insist that nobody uses his or her legally protected names or company trademarks, and that proper databases and records be kept to ensure that people can distinguish his or her goods from those of others. Botany has been trying to do this for the entire Plant Kingdom for well over 250 years.

Figure 3: (Left) Mountain Ash,

Eucalyptus regnans, in Victoria,

Australia, one of the world’s tallest

trees

Image from: Ray C (1932–1933). The World of

Wonder. Amalgamated Press, London.

Attempts have been made to avoid Latin by developing a ‘one plant one name’ approach to common names, an approach that may simplify databasing. This is done either by inventing names, or attempting to regulate them by producing standardised lists in which only one common name is provided for each species (or a preferred...