![]()

1

Carnivore conservation: the importance of carnivores to the ecosystem, and the value of reintroductions

Chris R. Dickman, Aaron C. Greenville and Thomas M. Newsome

Introduction

Carnivore populations are declining in most parts of the world, and concerns are held especially for the future survival of many large, charismatic and even formerly common species (Ripple et al. 2014). Because large carnivores typically sit at the top of their food chains and usually need extensive areas to hunt their prey, these species seldom achieve high densities. However, such carnivores are often reviled by humans due to their ability to attack and compete with us for food and space, and consequently are often culled, controlled or exploited directly to provide an economic return. On land, for example, several subspecies of leopard (Panthera pardus) and tiger (Panthera tigris) have been driven to critically low numbers over vast areas (www.iucnredlist.org), while in the marine environment populations of large sharks have suffered global declines of 90% or more (Myers and Worm 2005).

Yet, evidence is accumulating that the loss of carnivores – a process termed ‘trophic downgrading’ (Estes et al. 2011) – is not just depleting biological diversity at local, regional and global scales, but is also having damaging effects on the functioning and resilience of natural ecosystems. Indeed, Estes et al. (2011) argued that the loss of these animals may be humankind’s most pervasive influence on nature. Conserving carnivores, especially large species, is thus an urgent, albeit almost intractable, problem for managers and for society more broadly. Here we aim to first show, using a case study, that carnivores are critically important in maintaining functioning ecosystems and in enhancing the diversity of species these systems contain; and second, highlight the value of reintroducing carnivores to areas they once occupied or occupy now in low numbers. Although the term ‘carnivore’ may be taken to describe any animal that preys upon other animals, we restrict use of the term here to include vertebrates that feed principally on the flesh of other vertebrates.

The importance of carnivores

Large carnivores have long inspired awe (and fear) in people for their speed, power, grace and aesthetic appearance (Macdonald et al. 2015), as well as their ability to impinge upon human enterprises. Smaller species have been more likely to pass unnoticed, although the association between people and such carnivores as the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) and house cat (Felis catus) is long and well established. We acknowledge the importance of carnivores in human endeavours, but our primary focus here is on their effects on other species and the systems to which they belong.

Consumptive effects

Carnivores eat carrion or freshly killed prey, the most obvious effect of which is to reduce prey numbers. Yet, for a long time, this effect was thought to be trivial. Errington (1946), for example, suggested that carnivores had little influence on prey populations and took only individuals that would not survive anyway. Those individuals – the ‘doomed surplus’ – were considered to be largely young, old or sick, and would contribute little to overall population growth. More recent research has left no doubt that carnivores frequently do limit or regulate prey population growth. Some of the most compelling evidence for these effects comes from field experiments that manipulated carnivore numbers or tracked their populations over time. If such studies are conducted in a controlled and replicated manner, and prey populations respectively decrease or increase in response to changes in carnivore numbers, predatory impacts can be reliably inferred.

In addition to depressing prey populations, different species of co-occurring carnivores frequently interact and can mutually depress each other’s population size via competition. If two species differ in size, the smaller is almost always subordinate to the larger and – unless it is a social carnivore in a group – may be killed in direct encounters. The frequency and intensity of killing reach maximum when the larger species is two to 5.4 times the mass of the victim. Killing diminishes when the ratio of carnivore body sizes is less than two, due to the increased risks of injury to the combatants. It also decreases when the size ratio is >5.4, owing to the small benefit that large species could be expected to gain from killing smaller competitors (Donadio and Buskirk 2006). This situation, an extreme form of interference competition termed intraguild killing, becomes intraguild predation if the victim is eaten after being killed. If two species do not encounter each other directly but share similar food, habitat or other resources, the species that exploits those resources most efficiently will depress the population size of the other via exploitation competition. Both forms of competition can have profoundly negative effects on carnivore populations, distributions and resource use (Glen and Dickman 2005).

Although most encounters between carnivores are negative, at least for one of the species, some consumptive interactions have positive outcomes. For example, small carnivores may benefit from the presence of larger carnivores if the latter provide food for them. This situation can arise if the larger species flushes prey that are then accessed by the smaller species (e.g. the foraging activities of grey whales Eschrichtius robustus disturb fish and invertebrates in shallow marine sediments, making them available for a wide range of avian predators: Anderson and Lovvorn 2008); or if the larger species leaves the remains of prey that the smaller species can then use (e.g. carcasses that can be accessed by small species after larger species killed the animal or opened them up for scavenging). In rare situations, carnivores may confer mutual benefits on each other. Thus, the foraging activities of the dwarf mongoose (Helogale undulata) flush varied small vertebrates and invertebrates from cover, thereby increasing the prey-capture success of closely associated hornbills (Tockus flavirostris and T. deckeni). Mongooses benefit from the association by earlier and more efficient detection of predators; hornbills even respond to predators that potentially threaten only the mongoose, apparently learning the identities of specific predators from the responses of mongooses themselves (Dickman 1992).

Non-consumptive effects

Large carnivores and other predators have been termed ‘strongly interactive species’ because of their powerful and pervasive influence on other species (Soulé et al. 2003). As we have seen, carnivores often exert their effects on other species directly, by killing and eating them. This depletes populations of prey, but it can liberate both non-prey species by decreasing the levels of competition that they experience, and species in lower trophic levels by reducing populations of their own immediate predators. This latter situation is termed a ‘trophic cascade’. Conversely, carnivores may exert effects by modifying the behaviour of their prey and that of subordinate competitors. Scared or apprehensive prey and competitors often shift their activity or move to other habitats to avoid predators, and this in turn can liberate populations of other species with which they interact. Such non-consumptive effects are termed ‘ecological cascades’, and have been suggested to be more important than consumptive effects in shaping patterns of behaviour and foraging by prey (Laundré et al. 2001; Ripple and Beschta 2004). These cascades have been described in assemblages of placental and marsupial carnivores, as well as in assemblages of other vertebrates.

Case study

In the Australian context, the dingo (Canis dingo) provides a particularly helpful example of the pervasive effects that carnivores can have on other species and on non-living components of the environment. Space limits preclude citing all the research that has contributed to our current knowledge, but studies by Letnic et al. (2012), Newsome et al. (2015) and Lyons et al. (2018), and references therein, describe much of our current understanding.

The dingo was introduced to Australia from south-east Asia at least 4600 years ago, possibly on several occasions, and now occurs in virtually all terrestrial habitats across the continental mainland. It is absent from Tasmania. Its diet comprises a very wide range of prey, from insects to ungulates, although mid-sized and larger vertebrates such as rabbits, kangaroos, feral pigs, goats and emus feature prominently in many areas. It is the apex, or top, mammalian predator in Australia and, weighing up to 20 kg, is two to four times as heavy as the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and feral cat (Felis catus) that were introduced following European settlement. Recent studies suggest that the long tenure of the dingo in mainland habitats has allowed sufficient time for coevolution with native mammals. Thus, these prey can detect and respond aversively to dingo scent cues, minimising their risk of being killed and eaten. Although controversial, the development of prey’s innate ability to detect and respond to cues to dingo presence provides strong support for the idea that the dingo should be considered a native – or at least naturalised – species (Steindler et al. 2018).

Irrespective of its ‘nativeness’, the dingo is persecuted in many areas owing to its attacks on livestock, especially sheep. Animals are shot, poisoned, trapped, deterred by larger guardian animals such as maremma dogs, or physically excluded from flocks by fencing. In south-eastern Australia a ‘dog fence’ runs for over 5600 km from Jandowae, Queensland, to Penong, South Australia, and acts as a barrier to the movement of dingoes into the continent’s south-east. Although dingoes do occur inside the exclusion zone, they tend to be more numerous in coastal areas and in pockets through the Great Dividing Range than they are on the western slopes of the Dividing Range and the rangelands. Dingoes are absent or present at low density inside the dog fence but occur commonly on the other side of the fence, in Queensland and South Australia. The marked difference in dingo abundance on different sides of the fence provides great insight into the powerful effects of this carnivore on the structure and functioning of rangeland ecosystems.

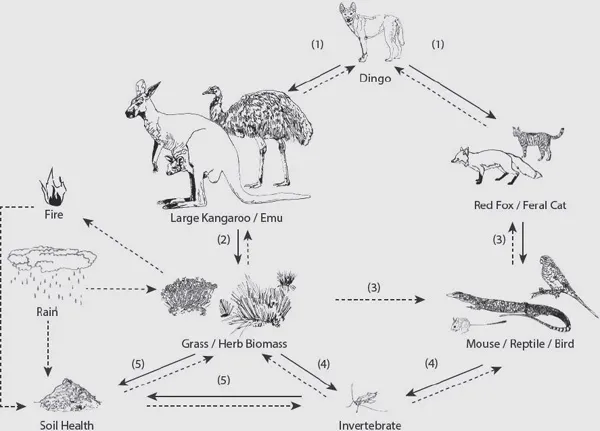

These effects can be viewed as flowing through two main pathways (Fig. 1.1). In the first, dingoes hunt large herbivores such as kangaroos and emus, suppressing their populations by up to two orders of magnitude outside compared to inside the dog fence. The paucity of dingoes inside the fence allows livestock to be run. Elevated populations of livestock, native herbivores and feral herbivores such as goats can place vegetation under heavy grazing pressure. In western New South Wales, for example, much of the native vegetation that provided nutritious fodder for herbivores was destroyed by overstocking of sheep in the two decades before 1900, and the region has never recovered. During dry periods in this region, such as the widespread drought in 2018, vast areas are turned into dust bowls with no grass or herbaceous cover and scant remaining shrubs and trees. Herbivore populations crash, and pastoral enterprises are placed under immense pressure. Outside the fence, by contrast, where dingoes continue to suppress herbivore populations, at least some native vegetation usually remains, even during long dry periods.

The effects of dingoes have further ramifications through the first pathway. By suppressing herbivore populations and facilitating increases in the biomass of grasses, herbs and shrubs, dingoes provide increased shelter and food resources for small mammals, birds and reptiles, as well as a high diversity of invertebrates (Fig. 1.1). These animals in turn are likely to facilitate the continuation of important ecological processes such as pollination, seed and spore dispersal, and the turning of soil that allows infiltration of rainwater and recycling of nutrients. Increased biomass of vegetation also leads to the formation of layers of leaf litter, which return organic material to the soil and provide rich microenvironments for microorganisms, fungi and diverse communities of animals. During dry periods, such habitats provide fuel for fires. Small-scale fires can generate mosaic landscapes that support diverse patches of different-aged post-fire vegetation and the animal communities that are associated with these patches, whereas large-scale fires may promote extensive stands of even-aged vegetation. In the absence of dingoes, these manifold and pervasive effects on plant and animal diversity and ecosystem functioning are muted or lost. Arguably, the dramatic effects of dingo absence would be less negative if livestock were absent from the rangelands. Whatever the case, there is little doubt that the vast, dry dingo-less sheep rangelands represent some of the most ecologically barren and degraded landscapes in Australia.

Fig. 1.1. Conceptual model of interactions that might be expected in the presence of the dingo (Canis dingo), shown by solid arrows, in a rangeland environment. Numbers in parentheses represent the predicted sequence of events. For example, if dingoes suppress large herbivores such as kangaroos and emus, then grass and herb biomass would be expected to increase. If dingoes also suppress mesopredators such as the European red fox and feral cat, small mammals (e.g. mice), reptiles (e.g. goannas) and birds (e.g. parrots) should increase, although this response may take longer to manifest than the response of vegetation. Invertebrates may also respond to improved vegetation condition and contribute to soil health. However, the strength of all interactions may be influenced by the extent of rainfall and fires (dotted arrows). This example, taken from Newsome et al. (2015), focused on interactions expected in Sturt National Park, New South Wales, but should be applicable to rangeland environments more broadly. Reprinted with permission.

The second pathway through which dingoes exert their influence on ecosystems is via their suppression of the activity and abundance of the red fox and feral cat (Fig. 1.1). These smaller carnivores may be killed (but not necessarily eaten) upon encounter with dingoes, and hence are under pressure to detect the presence of dingoes and reduce the risk of meeting them whenever and wherever possible. The dingo-associated risks to both the smaller carnivores are probably related inversely to the structural complexity of the habitat, with open treeless habitats being most risky (foxes and cats are more easily detected in the open, and have fewer options to escape) and forested and topographically rugged habitats least risky. The most compelling studies of the interaction between dingoes and the smaller carnivores show that the red fox is less active locally and regionally where dingoes occur, whereas feral cats show both spatial and moment-to-moment avoidance of dingoes, especially in open environments (see Letnic et al. 2012 for a review). Reductions in the activity or abundance of the smaller introduced predators in turn provide a reprieve for the many native species that fall prey to them. This outcome is important to ...