![]()

Chapter 1

Properties of soil

It is essential to appreciate the basic physical, chemical and biological properties of soil in order to understand the mechanisms of formation, relationships with landscape processes, and likely outcomes of different land management strategies. This chapter provides an overview of soil properties necessary for gaining this appreciation, and it defines terms and concepts used throughout the book.

Soil varies vary both vertically and horizontally. Our main focus here is on vertical variation and, in particular, on soil properties that can be observed in vertical sections (soil profiles). The soil profiles in the Compendium depict typical vertical patterns found in Australia. This means that a good appreciation of the great range of soil conditions found across Australia can be derived. However, for many practical problems, it is important to understand how soil properties and soil profiles vary across the landscape. Characteristic and predictable horizontal sequences of soils are found in most contrasting landscapes. These sequences of soils are referred to by various names including catenas, toposequences and soil landscapes, and they form the basis for mapping soils. A comprehensive account of these sequences is beyond the scope of this book, but indications of the main sequences present in a district can be obtained from local land resource surveys – some useful leads and suggestions for further reading are presented at the end of Chapter 5.

Soil morphology

Judging the appearance and feel of a soil

Australian languages have many words that describe the look and feel of soil (Table 1.1). Unfortunately, most of the words now in common use are ambiguous or poorly defined so they cannot be readily used to provide guidance on soil conservation and use. Soil scientists have developed agreed systems for describing the look and feel – or morphology – of a soil. In this country, the agreed system is found in the Australian Soil and Land Survey Field Handbook1, from which the following sections draw heavily.

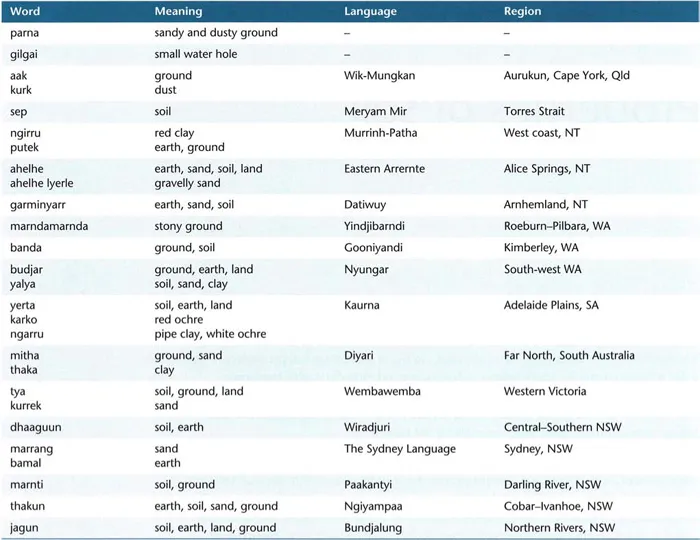

Table 1.1: A selection of Aboriginal words relating to soil – parna and gilgai are now used in the scientific literature2

Soil morphological properties are those that can be seen, felt, sometimes heard, and occasionally smelt or tasted. They include the thickness of soil layers, texture, colour, shape and size of soil aggregates, and accumulations of particular compounds such as organic matter or carbonate. Morphological properties can be described in the field using relatively simple methods and a summary is given below.

Soil layers and horizons

When observed in vertical section, soil profiles nearly always have layers. The layers may be inherited from the parent material; for example, soils on alluvial flats with regular flooding often have clear sedimentary layers (e.g. soil RU2, page 318). Inherited layering can also be due to other forms of sedimentation or reflect patterns in the rock from which the soil has formed.

Various soil-forming processes (pedogenesis) simultaneously create and destroy layers and it is the balance between these competing processes that determines whether clear horizons develop. For example, soil fauna (worms, termites and the like) often mix layers, while processes that involve the depletion and accumulation of constituents such as clay, organic matter and calcium carbonate can create distinct layers. These processes are discussed in Chapter 2.

Whereas interminable and surprisingly heated debates flourish over the naming and definition of soil layers, the following are now well accepted. They have been adapted from the Australian Soil and Land Survey Field Handbook.

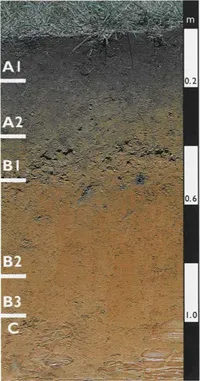

A soil horizon is a layer developed by soil-forming processes with morphological properties different from layers below or above it. Soil horizons are designated by a capital letter followed by numerals and lower case letters for subdivisions of various kinds. Figure 1.1 shows a soil profile with a common sequence of soil horizons. The major types of horizons are defined below.

A horizons

These are mineral horizons at or near the surface (topsoils) that have some accumulation of organic materials (less than O horizons). Typically, A horizons are darker than underlying horizons but they may also be horizons with lighter colours or lower contents of clay compared to underlying horizons. There are three types of A horizon.

A1 horizon

This is a mineral horizon at or near the soil surface that has some accumulation of organic matter. It is usually darker than the underlying horizons and it is the zone of maximum biological activity.

A2 horizon

This is a mineral horizon that has less organic matter, oxides3 or clay than the horizons above or below. It is a pale horizon and is common throughout Australia. Various degrees of bleaching are recognised with white or near-white layers being referred to as sporadically or conspicuously bleached, depending on its extent.

A3 horizon

This is a transitional horizon between A and B horizons but it is more like the A horizon.

B horizons

These subsoil horizons have one or more of the following:

• concentration of clay, iron, aluminium, or organic material

• a structure or consistence unlike the overlying A horizon and different from the horizons below

• stronger colours than the horizons above or below

Figure 1.1: A soil profile with many of the horizon types commonly found in Australian soil

Photograph: George Hubble, CSIRO

The B1 horizon is a transitional layer between the A and B horizons but it is more like the B horizon. The B2 horizon exhibits strongest development of the features listed above, whereas the B3 horizon is a transitional layer to the underlying material.

C horizons

These are layers below the A and B horizons composed of consolidated or unconsolidated materials. These materials are usually partially weathered and geological features are often evident. When moist, C horizons can be dug by hand.

D horizons

These are soil layers below the A and B horizons that differ in general character but are not C horizons. They cannot be reliably described as buried soils but they do have a contrasting pedological organisation to the overlying horizons.

R horizons

These are continuous masses of rock usually too strong to dig with hand tools.

O horizons

These horizons are dominated by organic matter that has accumulated on the surface of the soil. O horizons are subdivided according to the degree of organic material decomposition. These horizons are not common in Australia and are mostly restricted to moist or cool environments (e.g. alpine areas, swamps, wet forests).

P horizons

These horizons are dominated by organic materials, in various stages of decomposition, which have accumulated either under water or in very wet areas. They are often referred to as peat layers.

Colour

Colour is an obvious feature that has always been used for describing and identifying soil. In many cases, soil colour can provide valuable information on the subsurface environment both in terms of the processes of soil development and in relation to land use. Soil colour is determined by four main factors:

• the quantity and type of organic matter

• the nature and abundance of iron oxides

• inherited features from the original parent material or accumulations of mobile constituents4

• water content5

These factors, in combination with...