- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Are you wishing you knew how to better communicate science, without having to read several hundred academic papers and books on the topic? Luckily Dr Craig Cormick has done this for you!

This highly readable and entertaining book distils best practice research on science communication into accessible chapters, supported by case studies and examples. With practical advice on everything from messages and metaphors to metrics and ethics, you will learn what the public think about science and why, and how to shape scientific research into a story that will influence beliefs, behaviours and policies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Communicating Science by Craig Cormick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

COMMUNICATION TOOLS

7

Messages and metaphors

What the Brigadier sent to the Colonel: ‘Enemy advancing from the left flank. Send reinforcements.’

What was received: ‘Enemy advancing with ham-shanks. Send three and fourpence!’

– The Temperance Caterer, 1914

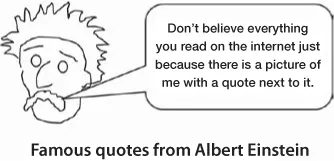

You have probably heard the saying by Albert Einstein that if you want to simplify your science in a way that the general public will understand it, you need to be able to explain it to your grandmother. That makes sense (unless your grandmother has a PhD) but what Einstein actually said was ‘all physical theories, their mathematical expressions apart, ought to lend themselves to so simple a description that even a child could understand them’.1

I agree, and rather than chatting up random grandmothers I prefer to try things out on children. After all, kids don’t have PhDs and they are infinitely curious – but they do need fairly simple concepts, visual explanations, and metaphors and analogies to help them understand complex ideas.

To get your message right you really need to be thinking what is going to work best for your audience – rather than what is going to work best for you.

So think of how you might explain your key messages to young kids. Use those types of language and visual explanations and you’ll probably do okay. For instance, if you are talking about the relative size of the earth and the moon, it’s logical if you are talking to a kid to say, ‘If you think of the earth as a basketball, then the moon would be a tennis ball, and it sits about seven metres/yards away’.

And you should be thinking that is the way to describe things to anybody. Because, to be totally frank about this, if you haven’t got your message right, all the best science communication theory and practice and support is probably going to be wasted.

The US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report, Communicating Science Effectively, makes a couple of key points to bear in mind about messages:

Don’t believe everything you read on the internet just because there is a picture of me with a quote next to it.

• Science communicators at a minimum need to be aware that messages from science may be heard differently by different groups and that certain communication channels, messengers, or messages are likely to be effective for communicating science with some groups but not with others.

• Tailoring scientific messages for different audiences is one approach to avoiding a direct challenge to strongly held beliefs while still offering accurate information. People tend to be more open-minded about information presented in a way that appears to be consistent with their values.

• People associate a message with a source, and come to believe the message based on trust in that source. Yet over time people will remember the content of the message more than they remember the source of it.

• It can be difficult to communicate accurate information about science in the face of many competing messages and sources of information.

• It is important to test individual messages carefully before they are used.2

The importance of testing your messages is iterated by many reports into developing effective messages, to best address the chances of your message being misinterpreted. This could be due to many factors, including the messenger, audience characteristics or things that interfere with your message being conveyed accurately.

Communication researchers agree that the message a communicator intends to convey is never exactly the same message that the recipient receives.3

In general, audiences are more likely to pay attention to messages that are succinct, timely and relevant to them. So whenever possible, find a way to frame a message that includes your audience.

For instance, if you are talking about the relative size of and distance between the moon and the earth, you could say: ‘When you look up at the moon in the night sky and wonder how far away it is, you probably think of the many pictures you have seen of it in text books, where it is relatively close to the earth. This is, however, inaccurate. The distance to the moon is about 30 times the diameter of the earth.’

Use of language

I’m sure you have all heard of the KISS approach to language use – Keep It Simple Stupid. It is something to remember as your choice of words can affect an audience’s perceptions and responses to your messages. (Indeed, even adding the word stupid to the end of that acronym can insult some people). The no-no list to keep a sharp eye out for includes:

• jargon that has a meaning to you, but maybe not to a general audience

• acronyms, that like jargon, feel like a secret code that the audience is being excluded from

• quotes from academic papers – these often work in the context of a published paper but don’t translate too well to messages for general audiences or the media (the academic way of writing is useful for academic publishing – but almost no other situation at all)

• euphemisms that work for you, but might not be familiar to your audience, like NIMBY (not in my back yard) – both a euphemism and an acronym (as well as a bit insulting) so a triple no-no.

• taking an analogy too far. Analogies are very useful for explaining complex things – but you do need to acknowledge when an analogy breaks down.

The US FDA Report Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide, cautions that any message you develop based on your own intuition should set off alarm bells. The report states:

It’s exciting to have a flash of insight into how to get across a message. Indeed, the best communications typically do start out as an idea in the communicator’s head. Unfortunately that’s how the worst ones start out, too. Such intuitions can miss the mark, in part, because the communicator is often not part of the target audience.3

Getting the message right

Good messaging, as opposed to the no-nos, is based on:

• having pretested your key messages with the audience

• shaping the message to the particular needs of the target audience, so it is:

• giving the key messages at the start of the communication

• telling the target audience who you are and why you are talking to them (if speaking to them)

• using pictures and stories for illustrating things

• checking your audience has not only received your message, but understands it

• concentrating on addressing not just what you did, but the ‘So what?’ or the ‘Why does it matter?’ of your message

• repeating your key message in different ways.

The message box

Washington-based science communicator Aaron Huertas says there are lots of tips, methods, schools of thought and best practices for developing effective messages in science communication. And he likes them all.

By that, he means he doesn’t stick to just one method, and views each as a tool rather than a rigid formula.

Having your key messages thought out and then written down can be a good way to focus your thinking. I’ve been in workplaces where the key messages of the organisation are printed out and mounted on the wall, so nobody has an excuse for forgetting them when they are suddenly asked to tell what the agency is all about.

Case study: Testing a communication message

The US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine had been concerned that uptake of engineering among young people was being hamp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Ground Rules

- Communication Tools

- When Things Get Hard

- Science Communication Issues

- About the author

- Endnotes

- Index