![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Palaeontology – the study of fossils – is arguably one of the most readily accessible sciences. Its recreation of lost worlds populated by real-life monsters provides fuel for the imaginations of adult and child alike. The painstaking research that lies behind this popular imagery is no less fascinating. The basic work of palaeontologists involves the meticulous excavation, preparation and interpretation of fossils. Fossils are the remains of animals and plants found embedded in rocks either as petrified hard parts or as moulds, casts or tracks. In many cases, fossils are extremely common and can be found by anybody who knows where to look. This book aims to encourage this interest by providing a comprehensive overview of some of the most spectacular Australian fossils – those from the Mesozoic Era, the ‘Age of Dinosaurs’. The Mesozoic lasted from ~251 to 65 million years ago, a time when dinosaurs roamed the land, giant sea monsters cruised the oceans and the earliest ancestors of Australia’s unique modern animals and plants began to appear. The ancient geography and environments of Australia during the Mesozoic are difficult to imagine. For example, the current landmass did not exist as an island continent, but formed an isolated south-easterly peninsula of a vast supercontinent called Gondwana. This comprised present-day South America, Africa and Madagascar, India, Antarctica and Australia, with the Australian portion situated close to the southern polar circle and, at times, experiencing temperatures close to freezing. Indeed, evidence exists for seasonal sea ice and even permafrost. Such conditions are virtually unique to the Australian Mesozoic record and thus constitute one of the most unusual and globally significant habitats from the Age of Dinosaurs. During much of the later Mesozoic, Australia was nearly totally submerged beneath a shallow inland sea. The muddy sediments from this ancient ocean form an extremely plentiful source of fossils, and are one of the most complete records of life from this period anywhere in the world.

Much of the research on Australian Mesozoic fossils is in the form of technical papers, university theses and conference abstracts that can be difficult to access and collate. This book aims to encapsulate this literature by summarising current work on Australian Mesozoic vertebrates (backboned animals), while also providing a palaeobiogeographical overview of the associated invertebrates (animals without backbones) and different land plant settings. We hope that this information, together with the graphic interpretations and reconstructions, makes this book a useful primary reference, and spurs people to further investigate Australia’s amazing Age of Dinosaurs.

How this book is arranged

Understanding the context of fossils and their ancient environments requires some basic background information. This is provided in the introductory chapter, which examines the nature of sedimentary rocks and how fossils are formed, the concept of geological time and the dating of fossil-bearing deposits, the mobile nature of the Earth’s crust and the theory of plate tectonics, how fossils are recovered, prepared and interpreted, and lastly how we understand the evolutionary relationships of organisms through time.

Chapter 2 describes Australian floras, faunas and environments during the Mesozoic and includes an overview of the relevant time-scales and maps showing the changing geographic placement of the continent.

The following chapters present a more technical overview of Australian Mesozoic fossils. Each of the major time periods – the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous – is examined in detail, with a brief introduction to their respective geological context, environments and important rock units/localities. The Triassic is discussed in Chapter 3, which examines life from the beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs. The major types of land plants, invertebrates and vertebrates are reviewed and special emphasis is placed on the vertebrate fossil record as a distinctive indicator of time-frames. This format is also applied to the Jurassic in Chapter 4, and the Cretaceous in Chapters 5 to 7. Because the vast majority of Australian Mesozoic fossils are of Cretaceous age, this period is divided into three parts. Chapter 5 examines the Early Cretaceous marine record, representing the time when a vast inland sea inundated much of the Australian continent. Chapter 6 looks at fossils from the contemporary Lower Cretaceous terrestrial and freshwater deposits. Finally, Chapter 7 investigates the remains of life from the end of the Age of Dinosaurs, after the inland sea had disappeared.

Wherever possible, graphic interpretations are included to assist with understanding the relevant anatomical structures. Reconstructions, based directly on the fossil information, show how the organisms might have looked in life. This book frequently uses technical terminology. Therefore a glossary of important terms is included at the end, together with a list of relevant scientific articles to guide further specialist reading.

Sedimentary rocks and the formation of fossils

Ever since the rocks of the Earth’s crust first solidified from a molten state some 4.6 billion years ago, the forces of erosion have been wearing them away, reducing them to sediments. These sediments are carried and deposited by rivers, lakes and seas into hollows in the Earth’s crust where they eventually compact to form successive layers of sedimentary rock. These may be uplifted into mountain ranges or downwarped into basins and, through the actions of wind and water, provide new areas upon which the cyclical forces of erosion and deposition can work. Indeed, the Earth’s surface as we see it now is a product of these continuous cycles with rock formation, erosion and crustal movements all contributing to the development of our modern geography.

The successive layers of sedimentary rock can be read much like the pages of a book. By examining the chronicle of their formation, we can understand the forces shaping the surface of the Earth. Similarly, to appreciate the large-scale processes affecting the development of life we must first understand its history. The best way to do that is with fossils, the remains of animals and plants preserved in sedimentary rocks. As sediment layers are laid down in rivers, lakes and seas, parts of animals and plants can become incorporated and thus be protected by rapid burial, low oxygen conditions or acidic/mineral-rich water, from decay. As the sediments are compacted and turned into rock, the organic remains buried within them become mineralised and are preserved in a petrified state.

The most common types of fossils are microfossils (microscopic fossils). These typically include the tiny calcareous or silicified skeletons of marine plankton or the spores and pollen grains produced by plants. Microfossils are particularly important for determining the age of sedimentary rock strata. This is because their small size allows for easy subsurface sampling using drillcores. In the case of spores and pollen, their resistant waxy outer covering ensures preservation under a variety of conditions.

This book is primarily concerned with macrofossils (those visible with the naked eye), which include remains such as shells, wood or bones. These can be preserved in a number of ways depending on their nature and the conditions that prevailed during and after their entombment in sediment. One example frequently encountered in marine strata is preservation in rounded limestone boulders called concretions. These are produced when decomposing organic material prompts a chemical change in the surrounding sediment, forcing calcium carbonate (CaCO3) out of solution. This then precipitates as limestone, which encases the hard organic remains, sometimes with phosphatised soft tissues and other inclusions such as gut contents.

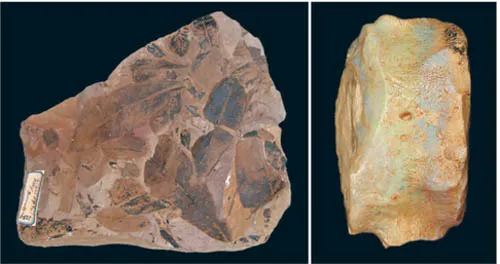

There are many kinds of planktonic fossils. Common examples include dinoflagellates and foraminiferans. These minute single-celled eukaryotic (complex-celled) organisms move using whip-like threads or extrudible pseudopodia. The fossil dinoflagellate skeletons shown under magnification were extracted from Lower Cretaceous high-latitude marine sediments in northern South Australia. Dinoflagellates have been used extensively, together with fossilised plant pollen and spores, to determine the relative ages of Mesozoic strata in Australia. Images courtesy Neville Alley and PIRSA.

Fine internal structures can also be fossilised by replacement with minerals such as silica (SiO2). This is the primary component in petrified wood and opalised fossils. Opal fossils are very commonly found in Australia. They occur when hydrated silica (SiO2.nH2O) directly replaces the organic material, thus preserving a natural replica of the fine surface detail, and sometimes preserving complex internal structures. The process of opal formation is poorly understood, although it may be linked to weathering and cyclical fluctuations of regional watertables (prompting dissolution of opal from silica-rich groundwater), or the actions of bacteria living in the sediment (decomposing organic material and secreting silica as a waste product).

Detailed external preservation can also be facilitated by fine mud or volcanic ash. When this settles in still water bodies such as lakes or poorly oxygenated deep oceans it can act as an inhibitor of decay, creating a high-resolution impression of the animal or plant. This form of fossilisation occasionally preserves remnants of the soft tissues as a thin carbonaceous layer. Common examples of carbonised impressions include delicate leaves and fern fronds, which may show evidence of microsopic surface structures replicated in the mud long after the actual plant material has decayed. Original fossil plant matter is also preserved as coal. This is the carbonaceous remains of plants that grew in localised swampy environments over long periods of time. The immense volumes of accumulating plant matter compact under their own weight to form a coal seam. None of the original plant structure is left within the coal (having been destroyed by compaction); nevertheless, interspersed layers of sediment (usually shale or fine sandstone) can preserve fossils of animals and plants living in the original swampy habitats.

Vertebrate fossils preserved in limestone concretions can be treated with acetic acid to reveal the encased bones. This ichthyosaur skull is shown both during the acid leaching process (left) and after complete extraction (right).

Types of fossil preservation. (Left) Carbonised leaves belonging to the Permian gymnosperm Glossopteris from Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia. (Right) An opalised plesiosaur vertebra from Andamooka, South Australia.

A preservation type that does not leave any original organic material is moulding and casting. This occurs when organic remnants such as shells are destroyed via dissolution in acidic groundwater or through the effects of erosion, but leave a mould of their external surface in the surrounding rock. Frequently, mud or minerals may fill parts of the structure (e.g. the shell), leaving a cast of the internal surfaces.

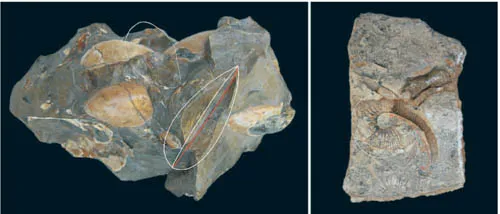

Shell moulds of the mussel-like bivalve Eyrena encrusting a piece of fossilised driftwood. This specimen comes from the Lower Cretaceous marine rocks of South Australia.

Mould and cast fossils form when sediment fills a cavity left by the original organic material. (Left) Impressions of the mussel-like bivalve Eyrena. Weathering has removed the original shell (reconstructed) to leave an impression in the limestone. (Right) An impression of an ammonite shell that has been naturally cast in limestone. Part of the cast has been destroyed by fracturing and erosion on the surface.

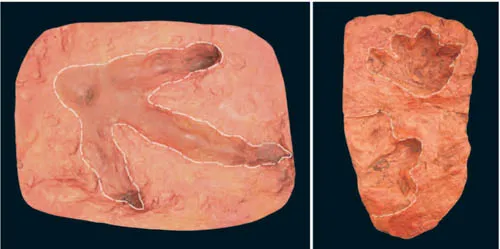

A similar moulding and casting process is involved in the preservation of plant and animal traces such as root casts, burrows, feeding marks and footprints. Collectively these are termed ‘trace fossils’ and they can be useful in determining aspects of behaviour in extinct animals. Trace fossils are generally preserved when sediments are deposited quickly over moisture-rich substrates. For example, when an animal walks across a soft muddy surface the weight of its body creates a series of depressed hollows or tracks showing the impact of its feet. The subsurface sediments are also deformed by the downward pressure of the foot, producing a series of underprints or ‘ghost tracks’ in the underlying sediments. As more mud is deposited over the exposed trackway (perhaps by floodwaters), the original footprints act as a mould from which a natural cast is made in the overlying layer. As the mud is compacted into rock and exposed at the surface by erosion, the tracks may again become visible as positive or negative reliefs on the successive rock strata. Less-defined moulds and casts can also be left by the underprints.

Trace fossils such as footprints are an important source of information about locomotion and behaviour in extinct organisms. (Left) A large theropod footprint from the Lower Cretaceous Broome Sandstone near Broome in far north-western Western Australia. (Right) Possible stegosaur footprints, also from the Broome Sandstone of Western Australia.

Geological time and the fossil record

The ages of the Earth, from its initial formati...