![]()

CAUSES OF WATER SHORTAGES

There are three major causes for the current restrictions on water use in our gardens.

The main cause is reduced rainfall, which in turn is due to the increasing concentrations of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane in the atmosphere. The carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide come from our burning of fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – that produces the energy we use for heating and cooling, for running our appliances, and for powering our factories, vehicles and aeroplanes. The methane comes from rice paddies, cattle, rubbish dumps and, increasingly, from peat bogs as they thaw, and deep ocean deposits as ocean temperature rises. The higher the concentration of these gases in the atmosphere, the greater is the reduction in the loss to space of heat generated when the sun’s rays hit the earth’s surface. The resulting rise in the average temperature of the lower atmosphere increases evaporation of water. Water in the atmosphere is a powerful greenhouse gas, so the warming is further increased.

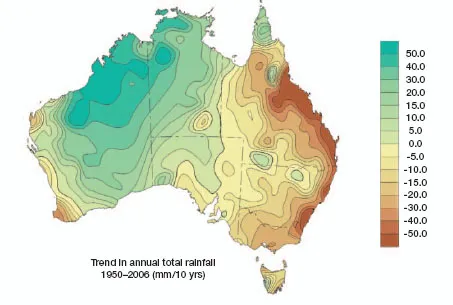

One result of increasing atmospheric temperature is that circulation patterns in the atmosphere shift. This means lower average rainfall across southern Australia, but increased rainfall in the tropics and in parts of central Australia (see the references listed in Appendix 1 for detailed information). Scientists have shown that when rainfall decreases by 10%, there is 30–50% decrease in runoff into streams and reservoirs. The trend towards decreased rainfall started about 25 years ago in south-western Western Australia and, more recently, in south-eastern Queensland, but it is now universal in southern Australia.

There is therefore a direct link between our use of energy and lower water levels in our reservoirs. And because Australians use more energy per person than do the citizens of any other industrialised country, we are major contributors to our lack of water. More widely, the combination of rising living standards throughout much of Asia and the Middle East, and rapidly increasing populations, is bringing billions of people in these regions up towards our energy use and greenhouse gas production levels.

A second cause of water restrictions is increasing population. At a local level, the combination of increasing population with drastically lower water levels in reservoirs has an inevitable result.

Australian rainfall trends, 1950–2006. (Bureau of Meteorology)

A third cause is lack of vision by some politicians. The first warnings about global warming and its possible consequences were made by scientists nearly 40 years ago. Solid evidence has existed for at least 15 years, yet the leaders of countries whose citizens are the biggest polluters have taken little action until very recently. Even now, when the evidence is as solid as anything can be, much of the political response is nowhere near what is necessary to avert catastrophe for our grandchildren.

Some hopeful signs

Despite the size of the problem, there are many hopeful signs:

- decreased amount of water used in gardens, generally with minimal effect on plant quality

- voluntary reductions in energy use by increasing numbers of people

- general acceptance and practice of shorter showers and many other water-saving measures

- reduction of carbon footprint by parts of Australian industry

- small increase in the proportion of total energy production from wind, the sun, geothermal sources and waves

- phasing out of incandescent light bulbs

- improved energy efficiency in electrical appliances

- purchase of carbon offsets to plant trees and generate green energy

- some moves to require energy efficient design for new homes and other buildings

- slight decrease in average distance travelled by private car

- some increased use of public transport, motor scooters, bicycles and feet.

Gardens are a part of the cure

Gardeners make a significant contribution to reducing the effects of global warming. About 70% of the green cover in our cities is in home gardens. The main environmental effect of this greenery is that, by providing shade and natural evaporative cooling, it cools the area around our homes in summer, so reducing – even eliminating – the need for energy hungry air conditioning.

Our plants soak up carbon dioxide and release oxygen back into the atmosphere. Gardening broadcaster Colin Campbell has suggested that there should be an ‘oxygen tax’ imposed on non-gardeners!

Food produced in a home garden, even if it is only a few herbs and salad greens, saves the energy required to transport it from distant farms to local shops. Recycling of food scraps through compost bins eliminates the energy cost of taking them to a landfill. Time spent planting, trimming, weeding and sweeping by hand in the garden is time that might otherwise have been used in energy intensive activities such as driving or watching television.

Gardens are places for relaxing from the stress of modern life. Anyone who has visited the slums or ‘concrete jungles’ of many cities soon learns to appreciate the softening effect that living plants have on a cityscape.

Our cities do not have to become almost treeless, as in dusty Iqueque, Chile. (Photo: Eleanor Handreck)

Still enjoying gardening at 87.

Also, by creating a pleasant setting for their home, gardeners increase its value by up to tens of thousands of dollars. They create employment for at least 50 000 Australians through their purchases of plants, fertilisers, tools and landscaping services. They provide habitat for birds and other wildlife. And on average they live longer and healthier lives than non-gardeners.

So before you feel guilty about using some of your allocation of municipal water in your garden, think of all the benefits you are providing to yourself, your family, your community, our Earth.

![]()

PLANTS AND WATER

KEY POINTS

Types of plants

How to select plants that are suited to your climate, environment and soil

How to avoid plants that might become weeds

Water use and the three types of photosynthesis used by plants

Roots and mycorrhizal fungi

How plants get water and cope with drought

Fertilisers and water use

Phosphorus-sensitive plants

There are at least 420 000 different types of plants on our planet, of which at least 25 000 are native to Australia. Through the combined forces of changing climatic and environmental conditions (cooling, heating, drying, wetting, etc.), differing soil properties and genetic mutation, each existing plant is the product of an evolutionary process that has left it superbly adapted to a particular set of climatic and soil conditions. For a plant to grow well in our garden, we must provide it with conditions that are reasonably close to those its parents had in their natural environment. We can do this in two ways.

We can use large amounts of energy and water to modify our garden so that it is suitable for plants from very different environments. That is what we are doing in our attempts in Australia to reproduce the gardens of northern Europe. Restrictions on water use are doing to this style of gardening what catastrophe did to the dinosaurs.

We can grow those plants that are either indigenous to our area (the native plants of our area), or come from other areas, both within and beyond Australia, whose climates and soils are broadly similar to ours. For any given area in Australia, this still gives us many thousands of plants from which to choose. This style of gardening uses plants which, once established, will grow well and look good with little extra water than is provided by rain. Any extra water needed can come from water stored from runoff from roofs and recycled from within the house. Much of any stored rainwater might well be used for producing fresh herbs, vegetables and fruit.

Pansy – an annual plant.

Types of plants

All plants fit into one of three categories:

1. Annuals grow from seed to producing seed to death within one year. Many garden weeds are annual grasses. Many of the bedding plants such as pansies, petunias and marigolds sold in garden centres are annuals. Shallow roots mean a need for frequent watering in dry weather. Water restrictions and the unwillingness of many gardeners to take the time needed to plant and maintain them have led to a rapid decline in their use in home gardens in favour of perennials.

2. Biennials need two years to complete their life cycle. They use the first year to produce the framework for the flowering of the second year. Parsley is an example.

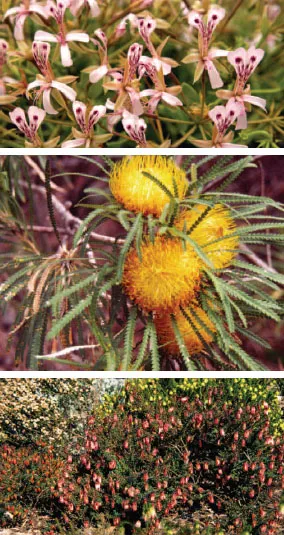

Alternatives to drought-sensitive perennials (from top): Pelargonium spinosum, Dryandra formosa, Darwinia macrostegia.

3. Perennials grow for many years, often flowering and producing fruit or spores annually. In its broadest sense, this term encompasses all trees, shrubs, ferns, bulbous and tuberous plants, the many small herbaceous plants and the rhizomatous and tussock-forming grasses. In gardening circles the term ‘perennial’ is generally restricted to refer to clumping herbaceous plants whose tops die back after flowering, but which grow new tops the following year.

Basic decisions

As a general rule, garden maintenance is easiest when perennials, in the broadest sense, form all or the larger part of the plantings.

...