![]()

ORAL HISTORIES OF DROUGHT

![]()

Four

Survival, making sense of crisis and ‘making do’

Social anthropologists on several continents and in various cultural contexts have argued that lived experience, and the memory of it, strongly shape human interpretations of climate.3 Recent research into how farm people use seasonal forecasts underscores this historical dimension of climate. As Roncoli et al. found in their study of meteorological meanings, ‘interpretations were anchored in their remembrance of desirable or dreaded situations they lived through, their observations about the conditions that brought them about, and their assessments of how they managed through them’.4 This book offers ample evidence of the ways the past shapes present understandings of climate, and so we begin this exploration of the richness of individual lives with a focus on discourse of survival.

In this first chapter of life stories, we find interpretations of the Big Dry anchored in the assessment of how generations of Mallee farm people have, in their words, ‘survived’ acute dry periods. Specifically, tales of drought – itself viewed as a defining feature of the Mallee climate – are framed by the remembrance of family-farm survival and rural community endurance. And, insofar as a survivor narrative assumes a stable self can be recovered, it seems talk of survival is only heightened by the likelihood of further social decline in rural Australia, not to mention the impacts of climate change.

The chapter opens with Hopetoun councillor and local newspaper editor Andrea Hogan, whose oral history presents a compelling narrative of community endurance through hardship, of a desire for control, and of identities under threat. Hogan’s survivor narrative forms a gendered tale of personal loss and subsequent self-empowerment; along the way, she unveils the ways Mallee people rationalise persevering through a harrowing situation. In effect, she outlines how drought amplifies rural perceptions of isolation and alienation from political power amid rural decline, exacerbating the ideological tensions inherent to contemporary rural social life. The capacity to endure hardship thus becomes a marker of local identity.

In the narrative of Mallee farmers Greg and Dorothy Brown, to follow, the lived experience of drought is considered foundational to both agro-environmental knowledge and Mallee farmer identity. Greg’s pursuits in rural politics have been driven by that experience; he believes ‘economic drought’ – an effect of political economy – impacts more severely on farm communities than a lack of rainfall, considered ‘a fact of life’ in the Mallee. In that context, climatic variability is considered normal, while anthropogenic climate change is foreclosed as an abstract, indeterminate, political construct of science and the media.

A recent history of crisis comes to the fore in the combined narrative of Bev Cook with Robert and Yvonne McClelland, three farmers who have been heavily involved in Mallee welfare-oriented organisations established to mitigate the socio-economic impacts of drought. In their oral histories, the experience of droughts in the early 1980s forms a historical marker of social crisis; they focus on this period as a means to emphasise the significance of history, politics and economics as determinants of risk in Mallee farming practice. Concurrently, crisis ‘survival’ affords a degree of optimism, ultimately amplifying the desire for historical continuity in an agricultural landscape of advance and retreat.

Finally, the story of Pam Elliott, an administrator at the Mallee region’s agricultural research station, sheds light on the interplay of lived experience and scientific expertise in deliberations on drought and climate change – reaffirming and questioning dominant ideas on the past, present and future. Here the experience of drought is perceived as localising the identities of Mallee people and place. In the face of threats to livelihood and identity, however, Elliott’s narrative alternates between a battler history of Mallee endurance and a more troubling contemplation of a land of evaporating promise.

Andrea Hogan: ‘drought’ as a loss of people who want their story heard

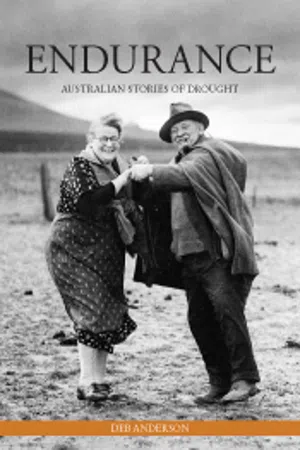

Bearing witness to drought: Hopetoun newspaper editor Andrea Hogan (2007). Mallee Climate Oral History Collection, Museum Victoria.

I interviewed Andrea Hogan in a deserted grandstand, sheltered from the mid-afternoon sun and overlooking a relatively well-watered part of Hopetoun, the football ground. Every few minutes, we could hear a raft of applause erupt from the adjacent Hopetoun Football Club. Inside the club (a site of battle, loyalty and upheld tradition in this country town), the Uniting Church was staging a Day of Listening for Drought Sufferers.

The clubroom was packed – with members of farm families, mostly, but also a bevy of businesspeople, politicians, public servants, church representatives and media personnel. More than 150 bodies were crowded around tables. Most had come from across the Mallee and neighbouring Wimmera region to attend the church-run event. Some had driven in from further south, from the regional centres of Ballarat and Bendigo; a handful of Melburnians had even travelled 400 km or so up from the Big Smoke. The Day of Listening was what brought me to Hopetoun that afternoon, too.

Across the north-west corner of the state, farm communities had been dealing with the impacts of below-average annual rainfall since 1996 – with acute dry spells in 2002 and 2004. By the time I interviewed Hogan in February 2005, these communities were, according to ABC Radio National, ‘desperate for anything but sunshine’.6 The Wimmera Uniting Church said the Day of Listening aimed to ‘respond in a way that honours the difficulties faced by those on the land in these areas’.7 The event was about listening not only to other people but also to a higher power; people were urged to hear others share their experiences of hardship, then join together in prayer. Through the ages, listening has been an integral aspect of religion in communities.8 And there in the club, the religious ritual also put the notion of rural community front and centre. It emphasised belonging as the fuel for surviving drought: to keep the faith amid despair.

It struck me that for this Day of Listening to succeed, however, it had to invite the devil of failure into the clubroom too. Poignantly, the event was shedding light on what local people heard was happening in Melbourne and Canberra – how they felt about those higher powers. Strong sentiments emerged in the clubroom about rural isolation and political alienation, a reprise of the so-called ‘country–city divide’. Some stories were signalling the failure of drought governance; most implied the need for a national agricultural policy framework that promoted real rural sustainability, given declining terms of trade. All stories shared that day touched on an ongoing threat, not just to rural livelihoods but also to a way of life, to rural identity. For to ‘speak out’ about drought, while necessary, was also to lay bare a fragile basis of existence: these were Australian farm communities caught on a production treadmill, locked into a cost-price squeeze and dependent upon rain-fed agricultural systems – in a part of the country recurrently bone-dry.9

Hogan, then 47, spoke up for ‘her town’. She was the editor of the local community-owned newspaper in its 113th year of publication, the Hopetoun Courier (with the full name, Hopetoun Courier and Mallee Pioneer, reflecting the preoccupations of historical identity). She was also the ward’s sitting member for Yarriambiack Shire Council.10

I’d met her earlier that day over a plate of lemon slice. Standing around during a break in sessions, feeling like an outsider – as a visitor, researcher, atheist and member of a farm family not local to this district – I’d impulsively sought out a place I felt useful and was drawn to the club’s kitchen, where about a dozen local women were clearing trays of homemade fare. There, Hogan struck up a conversation quickly. ‘I’m not backward in coming forward,’ she smiled, ‘and I usually shoot straight from the hip.’ She had long been ‘fairly vocal’ in the community, she added, particularly through the local Progress Association but also as president of every club, group or other organis...