![]()

1. Pathology of stress

Before discussing the pathological changes in native wildlife caused by particular infectious or other injurious agents it is important to consider those lesions which are regarded as the outcome of stress per se. As stress often occurs in concert with disease of quite diverse causes, it may be difficult or impossible to ascertain whether stress was the cause or consequence of lesions observed.

Obviously, knowledge of case history and clinical signs is helpful in interpreting lesions but such information is frequently inadequate or lacking in submissions of wildlife species – particularly those that are free-ranging. Although beyond the scope of this work, examination of haematological and biochemical profiles provide convenient and useful leads in establishing the contribution of stress to illness.

As a general guide, confirmation of a so-called ‘stress leukogram’ with neutrophilia, lymphopenia, eosinopenia and sometimes monocytosis is supportive of a diagnosis of stress-induced injury. While these changes appear mostly to be mediated by cortisol, further studies on wildlife species are needed to clarify pathogenic mechanisms. In one study of estuarine crocodile hatchlings, for example, haematological changes in response to environmental stress were not associated with significant changes in serum corticosterone. It was concluded that immunosuppression in young crocodiles may be independent of the hypothalamic–pituitary– adrenal cortical axis (Turton et al. 1997).

Too often in wildlife cases, ante-mortem specimens, notably blood, are unavailable. In order to better ascertain the contribution of stress to illness and death from necropsy samples, tissues sampled should include adrenal gland, thyroid, thymus, spleen, bone marrow, gonads and, where available, mesenteric and pulmonary lymph nodes (McFarlane 1997). In birds, inclusion of the bursa would be appropriate.

We discuss here the gross and microscopic lesions that, on the basis of history and other findings, appeared to have been primarily due to stress.

TERRESTRIAL MAMMALS

Dasyurids

The most adequately studied and documented stress-related disease in Australian native mammals is the annual synchronous total mortality of the male agile (brown) antechinus (Arundel et al. 1977) and dusky antechinus (Poskitt et al. 1984) during the post-breeding period. Although an event of natural occurrence and thus more accurately regarded as physiological, the observed signs and lesions, and mechanisms involved, are largely similar to those present in response to stressors of quite varied type.

Affected males typically die acutely and may not be observed ill. Signs include poor body condition with a marked negative nitrogen balance, polyphagy, some loss of fur, and lethargy. These signs coincide with elevated corticosteroid levels in plasma, neutrophilia and lymphopenia, and anaemia, perhaps associated with a high Babesia sp. parasitaemia of uncertain pathogenic significance (Woollard 1971; Barnett 1973; Cheal et al. 1976; Barker et al. 1978).

Changes observed at necropsy of males include haemoglobinuria, increased weight of adrenal glands, pinpoint pale foci of hepatic necrosis beneath the capsule and on the cut surface, gastrointestinal ulceration with variable but sometimes massive haemorrhage, and heavy burdens of gastrointestinal nematodes, tape-worms and lungworms (Barnett 1973; Arundel et al. 1977; Barker et al. 1978; Poskitt et al. 1984).

Microscopically, findings indicative of stress in male antechinus species in the post-mating ‘die off’ period include confirmation of focal hepatic necrosis with Listeria monocytogenes sometimes present, small gastrointestinal erosions or acute ulceration, in some cases associated with Capillaria rickardi infection and mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, increased cross-sectional area of the adrenal zona fasciculata with hypertrophy of cells of this zone and disappearance of lipid, and splenic haemosiderosis. In addition, there is severe involution of the spleen with follicles becoming small and poorly defined (Woollard 1971; Barnett 1973; Arundel et al. 1977; Barker et al. 1978). In a subsequent study of stress-related changes it was found that involution of spleen and lymph nodes was rapid, and that follicles and germinal centres depleted of lymphoid cells appeared as accumulations of amorphous material and reticulin fibres. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue remained unaffected, however, and involution of the thoracic thymus was unrelated to corticosteroid action (Poskitt et al. 1984).

Overseas, acute gastric ulceration in a captive, aged spotted-tailed quoll, with focal perforation and fatal haemorrhage into the lumen, was attributed to stress (Tell et al. 1993).

Possums and cuscuses

These species are very susceptible to stress. Stressors are largely the result of capture and confinement and include sudden change of surroundings, infrequent handling, overcrowding (especially of males during the breeding season) and intra-specific aggression (George 1982; Presidente 1982a) and psychological factors such as depression in a female ringtail possum that had lost her young through misadventure (Presidente 1982b).

As well as depression, signs of stress-related disease may include anorexia, profuse watery diarrhoea and dehydration, sometimes leading to death within three to five days. As in dasyurids, haematological examination may reveal neutrophilia, lymphopenia and eosinopenia, and plasma cortisol levels are elevated (Presidente 1978; Presidente and Correa 1981; Presidente 1982a).

In possums, lesions observed at necropsy considered primarily due to stress include dehydration, emaciation, gastric ulceration with oedema of the mucosa and submucosa and focal haemorrhages, colonic intussusception with haemoperitoneum due to rupture of a vessel in twisted mesentery, rectal prolapse and splenic lymphoid atrophy manifested as a small pale spleen with a wrinkled capsule and thin edges (Presidente 1978, 1982a; Speare et al. 1984). In brushtail possums, stress presumably associated with severe or painful traumatic injury may often result in hypersecretion of gastric fluids (Rose 1999) as well as gastric ulceration.

Microscopically, stress-related changes in possums are similar to those in other mammals and include adrenal cortical hyperplasia (perhaps with necrosis and haemorrhage which may target the zona reticularis), gastric haemorrhage and lymphoid depletion especially in the spleen but also in lymph nodes (Corner and Presidente 1980; Presidente 1982a). Focal nodular hyperplasia of the adrenal glands of free-ranging mountain brushtail possums correlated with free corticosteroid levels in blood, and adrenocortical cystic vesicles were noted in some animals (Presidente et al. 1982). In two Herbert River ringtail possums that were euthanased 24 hours after capture, lymphoid depletion with lympholysis was especially marked in splenic follicles. The paracortical lymphocyte density was more persistent but was also decreased. The extreme condition was a spleen devoid of follicles, containing only remnant collections of lymphocytes around some central arteries, leaving other arteries bare. Changes in lymph nodes paralleled those in the spleen, with germinal centres being most affected (Speare et al. 1984).

Again, as in other species, stress was noted to exacerbate other infectious diseases such as coccidiosis in the ringtail possum (Presidente 1978) and mycobacteriosis in the brushtail possum (Corner and Presidente 1980). In the latter case, disease in stressed animals spread rapidly, liver involvement was more severe and death occurred sooner than in less stressed possums.

Koalas

It is suggested that koalas may be inordinately susceptible to stress as exemplified by the frequent death of previously healthy wild koalas placed in captivity, the frequent failure of standard treatments to save sick and injured koalas, and the frequent absence of lesions at necropsy of emaciated koalas (Booth 1987).

Obviously, the clinical signs of acute stress, such as that induced by capture and restraint, may best be monitored by haematological examination or cortisol assay (Dickens 1975; Dickens 1978; Hajduk et al. 1992). Unless the stressor is acute intercurrent disease, it is unlikely in such cases that signs attributable to stress per se will be apparent. Therefore, in koalas, the clinical signs such as lassitude, anorexia and depression (Obendorf 1983; Booth 1987) and lesions attributed to stress mostly relate to stress of a prolonged or repeated nature such as inappropriate environment due to degradation or loss of habitat (Weigler et al. 1988), handling or chronic infectious disease.

Although no longer universally accepted as a discrete entity, a ‘koala stress syndrome’ (KSS) of unknown aetiology was described. By way of causation of such stress-associated disease it is now suggested that, for a range of reasons, a koala living on a low-energy diet ‘plummets into negative energy balance’ once appetite or food availability decreases. Also important is recognition of the concept that a specific disease (e.g. neoplasia) may act as a stressor in its own right (R. Booth, pers. comm. 2007).

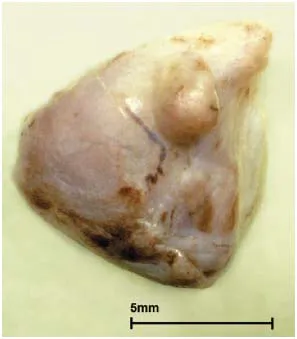

Figure 1.1 Koala adrenal. Cortical nodular hyperplasia, regarded as a response to stress. (Courtesy of R. Booth and the University of Queensland)

Males were predominantly affected by KSS. They were found...