![]()

1

Introduction

Graeme E. Batley and , Stuart L. Simpson

1.1 Background

Sediments are the ultimate repository of most of the contaminants that enter Australia’s waterways, and therefore it is appropriate that regulatory attention addresses the ecological risks that sediment contaminants might pose. There is increasing public awareness of, and concern for, the health of our waterways, and an expectation that water quality will be improved, but any improvement in water quality must address sediments as an important component of aquatic ecosystems and a source of contaminants to the overlying waters and to the ecosystem through the benthic food chain.

The sediments of many of the urban river systems, estuaries and near-shore coastal waters worldwide have high contaminant loads, derived largely from past industrial discharges and urban drainage. In many instances, there are elevated concentrations of nutrients, metals and metalloids and organic contaminants, especially polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Where regulations are adequate and met, the licensing of discharges has effectively controlled contaminant concentrations reaching surface waters from point sources; however, their concentrations in sediments often remain a concern. In many developing countries, regulations are weak and often not enforced. In highly urbanised areas, urban drainage, including road runoff, continues to represent a major source of contaminants that ultimately accumulate in sediments. Major point sources, such as partially treated sewage and discharges from mining and various light industries, contribute significantly. Rainfall events can result in leaching of contaminated land sites, with contaminants reaching surface waters and groundwater, both of which can contribute ongoing contamination to sediments.

Typically, as part of the management of contaminated sites, it is required that the risk of harm from any potential contaminants be assessed before the sites undergo any major disturbance through redevelopment or remediation orders placed on them. This involves an assessment of the potential toxicity, persistence, bioaccumulation, and fate and transport of the contaminants. Management and/or remediation of contaminated land and sediments is costly and needs to be based on sound science.

A range of sediment quality guideline values (SQGVs) for contaminants have been proposed internationally (Buchman, 2008) and they form the basis of assessments of the risk that sediment contaminants might pose to the environment. The sediment quality guidelines within the main water quality guidelines for Australia and New Zealand (ANZECC/ARMCANZ, 2000a) have recently been revised (Batley and Simpson, 2008; Simpson et al., 2013). Besides minor changes in some SQGVs, the revision outlines a scheme for the integration of multiple lines of evidence in a weight-of-evidence framework to be used in decision-making in cases where the results from chemistry and toxicity testing are equivocal. This reflects the latest in international thinking in relation to sediment quality assessment.

The original edition of this sediment quality assessment handbook (Simpson et al., 2005) was largely the output from a project to develop protocols for assessing the risks posed by metal-contaminated sediments. The project, funded by the NSW Environmental Trust, was undertaken jointly with researchers from University of Canberra and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. That study developed sensitive new sediment toxicity tests for estuarine–marine environments, examined metal uptake pathways for sediment-dwelling organisms, and characterised metal effects on sediment communities. In this new edition of the handbook, the information gained in those studies and related research conducted by the team has been integrated with the latest international research, to provide a more sound and practical basis for sediment quality assessment.

Since 2005, there have been several advances in methods for sediment quality assessment. A range of new whole-sediment toxicity tests have been developed covering both acute and chronic exposures. These tests have led to an improved understanding of controls on contaminant bioavailability and uptake pathways that can be used to refine the SQGVs. Biomarkers are being increasingly used to provide evidence of sub-lethal effects, while advances in ecogenomics are beginning to dramatically improve assessments of biodiversity in sediments. The improvements in these lines of evidence are coupled with advances in the application of weight-of-evidence assessments.

1.2 Sediment monitoring and assessment

There are several reasons why a sediment quality assessment might be undertaken. These might include:

•measurement of baseline concentrations at a pristine location;

•mapping the contaminant distribution in sediments in a waterbody to assess the distribution of historical inputs;

•determining the impact of known inputs (examples include stormwater runoff, industrial discharges, mining discharges, sewage and wastewater treatment plant inputs, shipping activities);

•assessing sediments requiring remediation (dredging, capping); and

•assessing the impacts of dumped sediments (from dredging activities).

These fall into three distinct categories: (i) descriptive studies; (ii) studies that measure change; and (iii) studies that improve system understanding (cause and effect). The assessment approach may be slightly different for each of these depending on whether the primary focus is on contaminant distribution, ecosystem health, or the potential for toxic impacts.

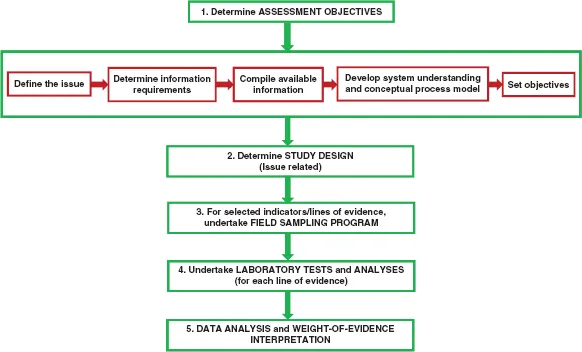

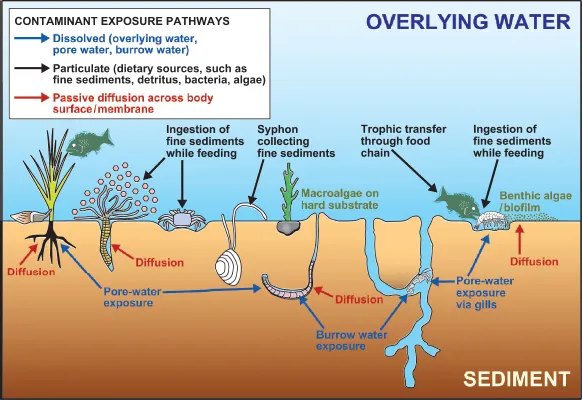

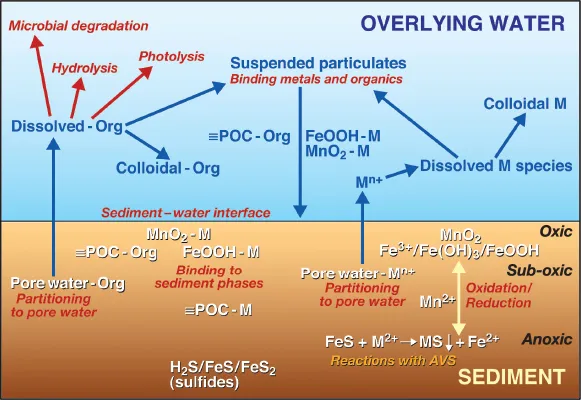

The first step in any assessment process (Fig. 1.1) is therefore the setting of the objectives (ANZECC/ARMCANZ, 2000b; USEPA, 2002a). As part of this process, the issue to be investigated (such as those in the list above) is determined, together with information requirements. Existing information is collated to help define a system understanding. This is then displayed in a conceptual process model which encapsulates all of the likely receptors and processes associated with the movement of contaminants and other stressors associated with the sediments. Examples of conceptual models for sediments are shown in Fig. 1.2 for biological receptors and their potential contaminant exposure routes, and in Fig. 1.3 for major contaminant processes influencing partitioning between water and sediment.

Figure 1.1. Monitoring and assessment framework for sediment quality investigations.

Figure 1.2. Conceptual model of organisms, receptors and potential exposure routes in sediments.

Figure 1.3. Conceptual model of major contaminant processes in sediments (where M indicates ‘metal’, POC is particulate organic carbon, and Org refers to organic compounds, so POC – Org is organics associated with POC).

The next step is to determine the study design, defining the indicators or measurements and tests to be made (the lines of evidence to be investigated) and developing the field sampling and analysis plan. After executing the field sampling and laboratory analyses, the final step is data analysis and interpretation on the basis of the weight of evidence (USEPA, 2002b,c). As a consequence of the data analysis, a need for lines of evidence additional to those originally chosen might be identified, leading possibly to a revised conceptual model, or at least a revised study design.

1.3 Sediment quality guideline values (SQGVs)

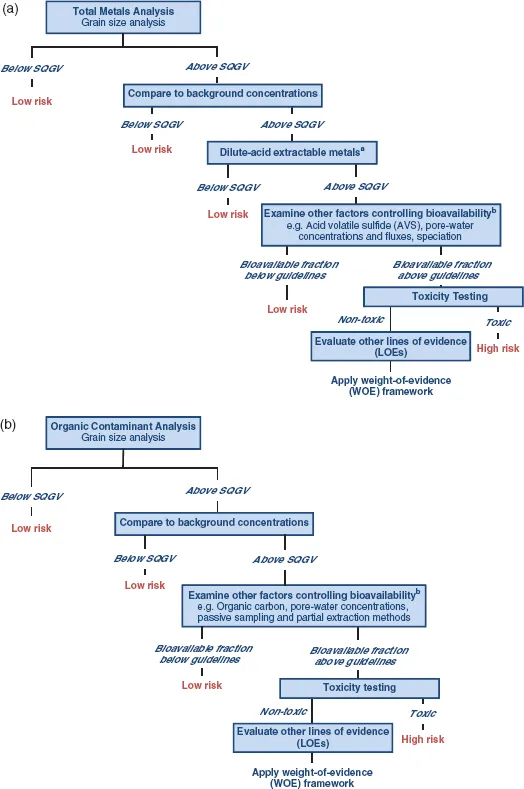

A key component of the assessment of sediment chemistry is the comparison of measured contaminant concentrations against SQGVs. Guideline values for Australia and New Zealand were released in 2000 and represented the latest in international thinking at that time (ANZECC/ARMCANZ, 2000a), but they have recently undergone revision (Simpson et al., 2013). Empirical SQGVs had already been adopted in Canada, Hong Kong and several states of the USA, and were also being considered in Europe (Babut et al., 2005; Buchman, 2008). In Australia in 2000, unlike elsewhere, the SQGVs were to be used as part of a tiered assessment framework (Fig. 1.4) in keeping with the risk-based approach introduced in ANZECC/ARMCANZ (2000a). As indicated later, SQGVs are considered during the evaluation of the ‘chemistry’ line of evidence (Section 1.4) but were derived through consideration of matching chemistry and effects data.

Figure 1.4. The tiered framework (decision tree) for the assessment of contaminated sediments for (a) metals, and (b) organics. SQGV = sediment quality guideline value. Notes: aThis step may not be applicable to metalloids (As, Se) and mercury (Hg). bSee specific methods on how bioavailability test results are used (Chapter 3 Section 3.6). Other lines of evidence may be considered using readily available tools for assessing toxicity, bioaccumulation, ecology impacts, or other lines of evidence such as biomarkers (see Section 1.4, Fig. 1.5).

There have been two approaches to the derivation of SQGVs: (i) empirically-based, and (ii) mechanistic approaches that are based on equilibrium partitioning (EqP) theory (Batley et al., 2005). The various versions of both approaches frequently converge in the prediction of effects on benthic organisms. In short, the science is able to define reasonably well the concentration ranges below which no effects are observed and above which effects are almost always observed. How...