![]()

CHAPTER 1

Creating healthy homes

The prime purpose of houses is to shelter us from harm. Positive energy living is about creating a home in a friendly environment, well protected from the elements and filled with fresh air. Our houses should be a safe haven, allowing us to thrive.

Are our houses fit for this purpose? When talking to immigrants to New Zealand from Europe or North America, the conversation will often turn to a lament about how cold our houses are. A friend from Canada recently exclaimed that the coldest she has ever been was in her house in Auckland. This is remarkable, because the mercury frequently drops to minus 20°C where she spent most of her life, whereas frost is so rare in Auckland that it is newsworthy. Many houses in Australia and New Zealand are cold and draughty in winter, and warm and stuffy in summer. Given that people in the developed world spend most of their time indoors, making our homes more liveable makes a lot of sense, and offers environmental and financial benefits.

So what are the hallmarks of a truly liveable home? This chapter explores what makes a home a comfortable and healthy place.

We love to be in touch with the outdoors but also crave the comfort of indoors. Consequently, we tend to be attracted to houses that offer indoor–outdoor living. But typically, this porosity is only then a delight when ambient conditions are pleasant. A Positive Energy Home in contrast allows us to enjoy the light and air we love, while sheltering us year round.

To achieve this, the indoor–outdoor flow needs to be controllable. Leaky homes are not able to exclude elements of the outdoors when they are not wanted. Just as a tap is a much better way to manage water use in the kitchen sink than a constant leak, homes that have ways to control the entrance and exit of the weather, pollutants, allergens, noise, smells and creatures are much more pleasant to live in! A clear boundary, called the thermal envelope, around the spaces where we live is necessary to control indoor comfort and air quality. To be effective, this boundary must not be interrupted.

With our lives predominantly spent indoors, we ought to be impelled to create wholesome indoor environments, especially for vulnerable subgroups of society, such as the very young, very old or otherwise fragile, who are likely to spend even larger portions of their time in the home.

The quality of the indoor environment is predominantly determined by the level of indoor air pollution, thermal comfort, noise and the quality of light. How the building fabric performs and how houses are ventilated and illuminated will impact markedly on the degree of refuge the indoor environment can afford. An intact envelope makes the indoor environment controllable, but we need to open up selectively for fresh air from the outdoors. The way we ventilate our homes is particularly crucial for thermal comfort and indoor air quality, and also impacts on the noise level of indoor spaces. As much as the building fabric and ventilation both have a key role in the provision of good indoor environmental quality, they are simultaneously tied to the energy consumption of houses. For example, a higher rate of fresh air supply will better dilute airborne pollutants, but without effective heat recovery; it will also result in excessive energy needs for the conditioning of indoor spaces and have implications for thermal comfort and noise levels. Likewise, larger windows will permit more solar gains – but also leak significantly more energy than opaque walls when the sun is not shining. How do we unite these conflicting goals? Design solutions to meet these challenges are covered in upcoming chapters, but first let’s talk about the key concepts that underpin the creation of comfortable, healthy and efficient homes.

Certified Passive House in Wanaka, New Zealand (Photo: Simon Devitt).

1.1 AIR CONTROL

Healthy homes need good quality air for us to breathe.

Indoor air quality is affected by contaminants that cause harm or irritation, have a bad smell or reduce our ability to see clearly (e.g. smoke). These contaminants can come from outside the home or are emitted indoors (e.g. from furniture, household products, stoves, pets and people). Depending on how strong or how toxic they are, these contaminants affect us to different degrees.

In the year 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified healthy indoor air as a human right (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2000). However, despite this declaration and the importance of air quality in our homes, there are few legal guidelines that describe safe levels of indoor pollutants in residential buildings. Most regulations either apply to workplaces or outdoor air. The impact on our wellbeing from air pollutant concentrations, however, will be the same, regardless of where we are exposed. Reasons for the absence of binding thresholds for residential environments may be the vast variety of potential contaminants and analytical equipment to measure them that can be quite intrusive, which is usually less problematic for outdoor or workplace air monitoring. Without turning our home into a laboratory: what options do we have for air control?

Ideally, a strategy for good indoor air quality in houses should start with avoiding the use of pollutant-emitting materials and substances, as well as filtering any harmful contents from outdoor air before it is let in. However, this is extremely difficult, because most building material manufacturers are not required to declare ingredients, and we often do not know the exact composition of other substances used in the household either. Do you know which pollutants lurk in your bathroom cleaning spray? In addition, breathing emits carbon dioxide (CO2), and odours and particles are a by-product of the typical usage of houses. With people actually living in their homes, controlling the source of contaminants can therefore never be complete. Filtering pollutants from outdoor air before it enters the home is only practically feasible when mechanical forces for ventilation are used, because the pressure generated by natural forces is insufficient for outdoor air to pass reliably through a filter.

Building blocks for good indoor air quality.

The next step up in the strategy for controlling indoor air quality in the home is containment of pollutants and excess humidity, for example, by using range hoods or extractor fans in kitchens and bathrooms to extract pollutants and humidity at their point of origin before they can spread. Pollutants can also be contained using coatings to prevent contaminants in suspicious materials, such as fibreboards, from becoming airborne.

Dilution of pollutant concentration levels by ventilating with fresh air is the last resort in this strategy – yet it can be the most reliable step of the way, because it is fully in our hands.

It’s only natural

Some schools of thought aspire to homes that are one with nature. As an example, a review of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House – a masterpiece of the International Style of architecture that emerged in the first half of the 20th century – positively remarked that:

‘[…] the house is very much a balance with nature, and an extension of nature. A change in the season or an alteration of the landscape creates a marked change in the mood inside the house.[...] the man-made environment and the natural environment are here permitted to respond to, and to interact with, each other.’ (Palumbo 2003)

The first owner, Dr Edith Farnsworth, agrees that there is hardly any separation, writing in her memoirs that she frequently found the house awash with several inches of water, and that inside, one burns in summer and freezes in winter. Being one with nature may not always be desirable!

Farnsworth House (Photo: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, ILL, 47-PLAN.V, 1–10).

Separating between ‘natural’ and ‘man-made’ is, in our view, not helpful for good decision making about houses. So-called natural building materials, such as rammed earth, may contain substances harmful to us, such as radon-emitting isotopes. Timber dust is another known carcinogen. Using only ‘natural’ materials is not a conclusive short cut to building a healthy home. We need to carefully examine all materials with regard to their potential to harm or help us. Positive Energy Homes can be built with materials that have undergone minimal processing, such as straw bales. The S-House in Austria, for example, did not use any plastic or metal for the construction of the building envelope, and several straw bale houses have been certified as Passive Houses.

Approximately 30 m3 of fresh air per person per hour are required to keep contaminant concentrations at bay. In addition, ensuring this fresh air is distributed effectively throughout the indoor environment also matters. For example, a very well-ventilated bathroom will not automatically lead to good indoor air quality in the other rooms of the house. There needs to be a driver to consistently deliver a sufficient amount of fresh air per person every hour. Even more fresh air is needed for spaces with higher pollutant source strength. For example, with someone smoking, a marked increase of the fresh airflow rate is needed to dilute harmful substances sufficiently. What drivers for this air exchange are available will be discussed in Chapter 3.

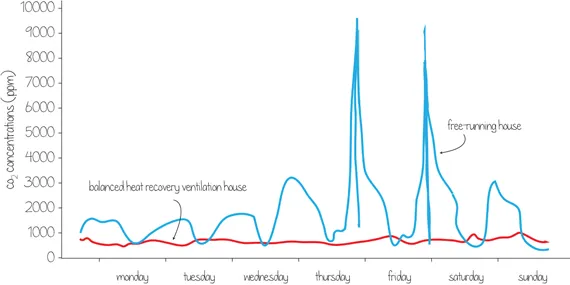

Monitoring of CO2 concentrations in the home is a recommended check to see whether the ventilation delivers the expected outcomes. CO2 levels are comparatively unobtrusive and inexpensive to monitor, and are indicative of other gaseous indoor air pollutant concentrations. Standards for mechanical ventilation quite often contain a CO2 threshold for this reason: 1000 ppm (ppm) is commonly used as a static value. Acute toxicity is only likely at concentrations exceeding this value 20-fold, but observed effects of CO2 concentrations above 1000 ppm include drowsiness, lack of concentration, headaches and increased heart rate. For example, the ventilation strategy in the free-running (no forced ventilation) house in the figure below is clearly not working. But even with a good ventilation system, it pays to check whether the volume flow that the system designer specified is actually getting to the spaces as planned, and meeting requirements there. Chapter 3 will explore these tests in more detail.

Monitoring of CO2 levels in two new three-bedroom houses in Auckland over a week in winter. Both houses were inhabited by four persons and a pet. Only the house with a balanced ventilation maintains levels below the 1000 ppm threshold, and shows a fairly consistent indoor air quality. This is in stark contrast to the free-running house, which relies on natural forces and someone opening the windows. CO2 readings here are strongly fluctuating, and far exceeding the recommended threshold at peaks.

Build-up of air contaminants can have a wide range of negative health effects, and dilution with fresh air is the most reliable way to prevent this. The provision of fresh air should not be an afterthought in the design of a house – it needs a clear concept, including a quality assurance process. It needs to be checked, though, whether the air provided is actually fresh. Outdoor air may not be unpolluted, and air leaking in through the building envelope may be impacted by fibres and other substances on its passage. Some standards allow for a maximum difference to outdoor concentration levels, rather than prescribing a static value. For a house in a forest, with lower CO2 outdoor concentrations, the threshold is lower than for a home next to the motorway, following this approach. Independently from the location of the building, intensities above 1500 ppm are viewed as concerning.

With a closed window, or an awning window kept ajar, CO2 levels are likely to build up in bedrooms overnight. On a winter night, the choices in such a bedroom are: keep the windows closed and achieve warm stuffy conditions, or open the windows and achieve cold fresh conditions. In other words, waking up with a headache or a stiff neck. Only when heat from the outgoing stale air is transferred to the incoming air can we be perfectly warm and fresh in our bedrooms overnight – we will explore this concept further in Chapter 3.

Cold or fresh?

If it is possible to provide air that is both warm and fresh, most people will agree that warmer bedroom temperatures are actually quite pleasing. However, you may think that you need it cold in your bedroom for a good night’s sleep. What leads to this perception? We associate cold with fresh air, and are therefore concerned that warm air is not fresh. In summer, when we can open windows wide, we can experience fresh and warm air together, and unless it is very hot, we sleep well. The same situation is possible in winter with the right ventilation strategy.

1.2 THE COMFORTS OF HOME

Thermal comfort is a state where there are no prompts to correct the environment by behaviour. If you are thermally comfortable, you can kick back and relax. This relaxation is important for our wellbeing: in the absence of thermal comfort, stress symptoms surface, with associated negative health effects.

Factors that influence thermal comfort are activity and clothing levels, air and radiant temperature, as well as air speed and humidity. All but the first two factors are largely determined by the building design and are explored in detail in this book. Clothing and activity levels are quite easily controlled by the residents, and we have made the assumption that most people will be conducting regular activities in typical clothing, rather than wearing a wetsuit or practising competitive wrestling just to be warm!

The human body core temperature needs to be stable within a narrow range of 37°C ±0.8°C. For thermal regulation, our body can resort to perspiration, respiration and dry heat transfer through convection, radiation and conduction. Because our bodies are always generating heat internally, we need to constantly reject excess heat to the surroundings to prevent overheating. When the temperature around our body is close to or above 37°C, we feel hot as our body struggles to reject the excess heat. Should there be high humidity in addition, most of the skin will already be wet, making it impossible to sweat for more cooling. This is a highly stressful and perilous state! Conversely, when too much heat is being lost to the surroundings, we feel cold and our bodies actively convert chemical energy to heat to maintain internal temperatures. Peripheral blood vessels constrict, breathing gets shallower and shivering sets in to increase heat generation. If the cool temperatures prevail, the body core temperature falls to life-threatening levels. For our body core temperature, a few degrees can make the difference between life and death. The ideal temperature for the body is when the air can readily remove the excess heat generated without over cooling. The balancing act of heat generation, heat absorption and dissipation requires energy, and is physically exhausting. Generally, we are thermally comfortable if the regulation requirements are kept to a minimum, and no effort is needed to balance our temperature with the environment.

Do we need to feel the cold?

Occasionally, it is claimed that we are better off feeling the cold in our homes. You hear people explaining that if we miss out on seasonal variation in temperature, our bodies become less resilient, and are easier attacked by pathogens. There is little support in science for this claim. Its validity is furthermore in question if we consider that our species successfully inhabits, and possibly even originates from, places with little seasonal variation in temperature. Yet, undoubtedly, feeling the cold at times can be refreshing. If you live in a place where it gets cold outside, opening a window in winter will let you experience the delight of frosty air. If you remember to close the window again after this episode, and you live in a Positive Energy Home, there will be no lasting impact on the temperature of your home or your power bill, so go for it, whenever you need your head cleared!

The challenge for designing a thermally comfortable home is that everyone has a different opinion of comfort at any given time. Constantly c...