![]()

1 Evolutionary history and taxonomy

Andrew D. W. Geering

What defines a shorebird? It is ironic that this fundamental question is often overlooked by the avid birdwatcher, who often can cite a long list of species that are called shorebirds but when pressed to explain why a curlew is a shorebird but an egret is not, is often left short of words. In this chapter, the evolutionary history and taxonomy of shorebirds are briefly described. It should be noted at this stage that the terms ‘shorebird’ and ‘wader’ are often used interchangeably, with the latter having more frequent usage in Australia, New Zealand and the UK although shorebird has been selected for use in this book because of the more intuitive nature and broader international popularity of the term.

As the name suggests, shorebirds are birds that commonly feed by wading in shallow water or saturated substrate along the shores of lakes, rivers and the sea. Not surprisingly, they share morphological features suited to this lifestyle such as relatively long legs compared to body size, and, most notably in sandpipers, long necks and bills. Also as a reflection of a predominantly migratory or at least highly mobile lifestyle, the wings are generally long, narrow and pointed, an adaptation to long distance flight. However, any definition based solely on lifestyle or morphological features tends to break down, as distantly related birds, such as herons and egrets, share many of these features through adaptation to similar ways of life (convergent evolution). Furthermore, there are internal contradictions within the group. For example, the Inland Dotterel occurs in semi-arid areas of Australia and rarely encounters free flowing water and the Greater Sand Plover swaps a littoral habitat in the austral summer for the steppes and gibber plains of the Gobi Desert in Mongolia during the breeding season1. Furthermore, lapwings, which have a sedentary lifestyle, have broad rounded wing-tips, an adaptation allowing manoeuvrability in the air2.

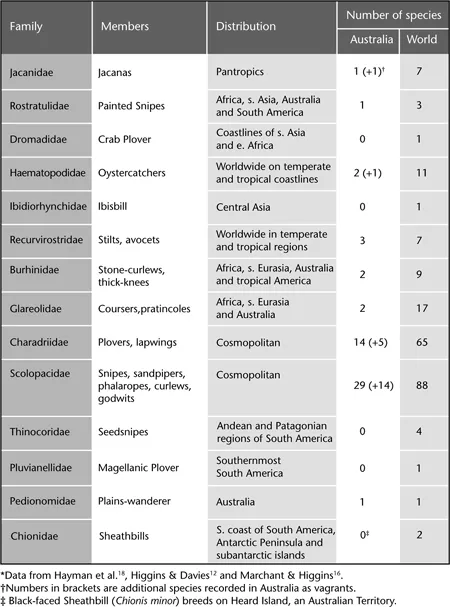

To provide a more accurate definition of what a shorebird is, one must turn to their taxonomy. The term shorebird refers to birds within 14 different families in the order Charadriiformes (Table 1.1). Conventionally, the Charadriiformes is divided into three suborders: suborder Charadrii, containing the shorebirds, suborder Alcae, containing a single family, the Alcidae (auks, puffins, murrulets and allies) and suborder Lari, containing four families, the Laridae (gulls), Sternidae (terns and noddies), Stercorariidae (skuas and jaegers) and Rhynchopidae (skimmers)3. However, it is now recognised that shorebirds are a paraphyletic group (that is, the group contains the most recent common ancestor but not all descendants of that ancestor) and revision of the higher order taxonomy of Charadriiformes is needed to accurately reflect evolutionary relationships.

Table 1.1 The families of shorebirds*

The evolutionary history of shorebirds

Charadriiformes is a very ancient group of birds, which from ‘molecular clock’ estimates, arose about 80 million years ago, probably on the supercontinent of Gondwanaland based on present day distributions of families within the order4–6. ‘Transitional shorebird’ fossils have been described from the late Cretaceous Period (146 to 65 million years ago) but taxonomic placement of these fossils is problematic because of the incompleteness of the specimens, all of which consist of single bones7. The earliest fossils that can be assigned with confidence to Charadriiformes date back to the early Eocene Epoch (56 to 34 million years ago) and originate from Europe and North America.

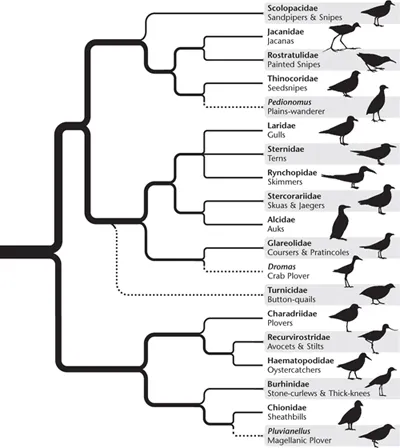

Recently, much progress has been made in understanding the evolutionary history of the Charadriiformes, particularly from analyses of both nuclear5, 8 and mitochondrial9, 10 genes and also using a ‘super-tree’ approach, combining trees derived from a range of different types of data11. A strong consensus has emerged as to the relationships within Charadriiformes, with three major groups identified:

1. Plovers, stone-curlews, sheathbills, oystercatchers, stilts, avocets and Magellanic Plover – sub-order Charadrii.

2. Sandpipers, jacanas, painted snipes, seedsnipes and Plains-wanderer – sub-order Scolopaci.

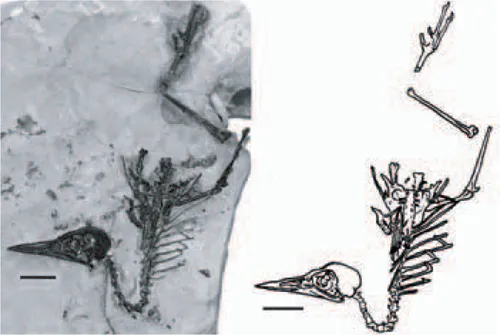

Fig. 1.1 Fossil of Morsoravis sedile, a primitive member of the Charadriiformes, from Palaeocene-Lower Eocene deposits in Jutland, Denmark. Scale bar = 10 mm. Figure reproduced from Dyke & van Tuinen7 with the permission of Blackwell Publishing.

3. Gulls, terns, skimmers, skuas, alcids, Crab Plover, coursers and pratincoles – sub-order Lari.

Contradicting previous views, the plover lineage is now considered to be the most primitive branch in the evolutionary tree and sandpipers are relatively more closely related to gulls than to plovers. This discovery has very interesting evolutionary implications, especially with regards to what are now viewed to be the most primitive morphological and behavioural traits of the Charadriiformes. For example, it has been speculated that the common ancestor of the Charadriiformes was likely a non-cooperative breeder with maternal care, the most common mating system of the plovers and allies6. At least some of the morphological features shared by distantly related shorebirds in the different lineages seem to have originated independently through a process of convergent evolution. Conversely, other taxa have exhibited rapid divergent evolution, such as the lily-trotting jacanas with their peculiarly long toes, whose closest relatives are the painted snipes.

Fig. 1.2 Evolutionary relationships of shorebirds (Charadriiformes) deduced using new molecular data. Phylogenetic positions of odd-ball taxa are indicated with dotted lines. Figure adapted from van Tuinen et al.6 by Robert Mancini.

There have been many other interesting findings from the above-mentioned molecular studies. Placement of the Plains-wanderer within Charadriiformes has been confirmed and this enigmatic bird from inland Australia appears to be most closely related to the seedsnipes from South America. The time at which these two groups split from each other has been estimated to be c. 46 million years ago, a date consistent with the separation of the Australian and South American continents. The stone-curlews are now thought to be most closely related to the sheathbills and Magellanic Plover, the latter traditionally classified in a monotypic sub-family within family Charadriidae. The genetic diversity within the genus Burhinus, containing the Bush Stone-curlew (B. grallarius) from Australia, the dikkops (B. capensis and B. vermiculatus) from Africa and the Peruvian Stone-curlew (B. superciliaris) from South America, is as great as the skimmer, tern and gull families combined, suggesting that classification of the stone-curlews and thick-knees at the generic and even family level needs to be revised. Analyses of both nuclear and mitochondrial genes support placement of the button-quails (family Turnicidae) within the Charadriiformes as a sister group to the Lari. The higher-level classification of the button-quails has been in a state of flux for many years because of problems with interpreting morphological characters due to convergent evolution between the button-quails and other terrestrial birds such as the true quails (order Galliformes) and rails (order Gruiformes).

Families Scolopacidae and Charadriidae

Families Scolopacidae and Charadriidae are the largest and most diverse groups of shorebirds and their taxonomy warrants further discussion. Scolopacidae, comprising 88 species in 23 genera, is further divided into seven sub-families, namely the Scolopacinae (woodcocks), Gallinagininae (snipes), Arenariinae (turnstones), Calidridinae (sandpipers), Limnodrominae (dowitchers), Phalaropodinae (phalaropes) and Tringinae (godwits, curlews and shanks)12. It is likely that the classification of Tringinae will be revised, as recent molecular analyses suggest that the shanks (Tringa spp.) are more closely related to the phalaropes than to either the godwits or curlews5, 8. Birds from all subfamilies, except Scolopacinae, occur in Australia and all are non-breeding migrants.

In 1982, a new species of sandpiper, called Cox’s Sandpiper (Calidris paramelanotos), was described13. However, more recent molecular studies indicate that Cox’s Sandpiper is in fact a hybrid between a Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea) and a Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melanotos)14. There are several other examples of inter-specific hybridisation in the genus Calidris15.

After Scolopacidae, the next largest family of shorebirds is Charadriidae, comprising 65 species in 10 genera. Charadriidae is further divided into two sub-families: Charadriinae (true plovers) and Vanellinae (lapwings)16. The origins of the true plovers have recently been investigated from analysis of mitochondrial DNA17. There have been some very interesting outcomes from this study. It is speculated that the true plovers originated in South America. For this group of birds, migration is thought to have arisen as a consequence of a shift in breeding rather than non-breeding range. Many birdwatchers have witnessed the unexpected arrival of a bird, far outside its normal range. Interestingly, the DNA analyses also point to this phenomenon occurring in prehistoric times, with two independent colonisations of Australia by the ancestors of the endemic plovers. ...