![]()

Part 1

Origins

Science can develop great mineral wealth of which, after all, only the rich outcrop has been exploited…

William Morris (Billy) Hughes

![]()

The Minerals Utilization Section

1940—1959

Overview

The widespread dependence of chemical industry on substances of mineral origin was generally appreciated, but there would appear to be scope for a much closer liaison, in many instances, between the actual producers of the crude minerals and those who are concerned with their processing, fabrication, and ultimate use by industry.

There are several ways in which the useful life of a mine, and therefore of its dependent industries, may often be prolonged. … physical and chemical treatment of crude ore is a very desirable, and often necessary, prelude to the utilisation of the ore by industry.

R.G. Thomas (1943)

The origins of the Division of Mineral Chemistry go back to March 1940 when the formation of a Division of Industrial Chemistry (DIC) within the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) was finally approved by Cabinet. The Minerals Utilization Section, usually referred to as Minerals Section, from which the Division of Mineral Chemistry emerged, was one of five original sections of the Division housed in the laboratory at Fishermen's Bend, Victoria, near the mouth of the Yarra.

It is noteworthy that this major building was completed in only two years, despite wartime problems, and was ready for occupation in 1942. Sir Ian Wark has written a detailed and excellent account of the founding and early years of the Division.1

The first Head of Minerals Section was Richard (Dick) Grenfell Thomas, who was appointed in 1940 as Senior Inorganic Chemist, responsible ‘for the analyst, for non-metallic minerals and for ceramics’.1 Almost two decades later, Thomas became the First Chief of the Division of Mineral Chemistry.

Richard Grenfell Thomas

While the laboratory at Fishermen's Bend was being built, Thomas and his staff worked at the University of Melbourne Chemical School, and Dr Wark and other members of the Division had rooms at 314 Albert Street, Melbourne, then the Headquarters for CSIR. Staff worked until 9 p.m. twice a week and worked Saturday mornings. On work-back nights during 1941, staff from the University laboratory joined their colleagues at Albert Street on library work, as the HQ building was blacked out, whereas University of Melbourne was not. There was little in the way of equipment except for the simplest alchemical bits and pieces, so moving everything in a truck to Fishermen's Bend when the laboratory was completed was no hardship. Thus, the main elements of the Division came together in 1942 in its first major laboratory.

This then is the start of our story. It is a story of the spawning and development of the Division of Mineral Chemistry; a story of the people who made it, of their achievements, failures and oft-times frustrations at their inability to commercialise promising laboratory-scale processes. Above all, it is a story of a continuing endeavour to benefit the Australian Mineral Industry.

The man who led this endeavour through to the founding and establishment of the Division of Mineral Chemistry was Richard Grenfell Thomas.

Section Head to First Chief

Thomas was a remarkable and versatile man with a keenly inquiring mind, and a great love of chemistry and minerals. Personal correspondence with colleagues gives some insight to his early life.2

He was born at Kapunda in SA on 29 March 1901, and his interest in minerals was engendered early in life when as a child he explored the old abandoned copper mine. In his writings, Thomas points out that the green copper ore from Kapunda is unusual in that it is an oxy-chloride, called atacamite (after the Chilian Desert of Atacama). It is not, as most people mistakenly call it, malachite. Some of his earliest experiments, as a child of about six, were to put bits of this green ore into a red-hot fire and obtain ‘the most splendid blue-green colours in the flame as the volatile copper compounds made their presence felt’.

Front view of the Lorimer Street Laboratories of the CSIRO Division of Industrial Chemistry (left of main entrance) and Division of Aeronautics (right of main entrance), taken on the occasion of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

As a student Thomas was fascinated by the table of chemical elements and set himself the task not only of learning their names and finding out where in Australia he could go to obtain the mineral source of each of them, but also of how he would go about processing a particular mineral to extract the element concerned in a more or less pure state. In 1919 Thomas, then 18 years old, rode horseback with an expedition, led by Dr H. Basedow (anthropologist, geologist, explorer and medical practitioner), from Farina (south of Lake Eyre) up the Strzelecki to Birdsville and beyond into Queensland. They returned south along the Cooper and came back to the railway line at Hergott Springs (now Maree). In a letter of 1967 Thomas recounts:

This (the journey) took some four months and several of our horses died of thirst and exhaustion and we were fortunate that we escaped a similar fate as it was a bad drought year. All the incidents of this trip made a deep impression on me and — as is so often the case — only made some sort of repetition inevitable! (I have always indulged a fanciful idea that the spinifex injects an unsettling ‘drug’ into those who, early in life, submit themselves to its irritating prickly hypodermic action!)

My interest in the Mt Painter uranium ores dates from as far back as this as my diary of the time says, ‘in the far distance the blue peaks of Mt Pitts and Mt Painter are visible. It is there that the uranium minerals occur’.

During his student days at the University of Adelaide, he developed life-long friendships with such notables-to-be as Mark Oliphant3 and Arthur Alderman. Later, Thomas was to induce Alderman to join his fledgling Minerals Utilization Section in CSIR to look after the cement work which had just started. On Thomas's advice, the cement group later became a separate section with Alderman as its head. Alderman eventually returned to the University of Adelaide as Professor of Geology, but not before he had established a remarkably successful collaborative study with the cement industry.

As a student, Thomas also developed a close personal friendship with Sir Douglas Mawson, Professor of Geology and Mineralogy at the University of Adelaide from 1921 to 1952 and arguably the greatest of Antarctic explorers. In 1968, Thomas's long-time friends, Dr Reg Sprigg and his wife Griselda, purchased the 61 000 hectare (235 square miles) property that covered all the magnificient, rugged area of the north eastern extremity of the Flinders Ranges and co-founded the Arkaroola-Mt Painter Sanctuary. In their book Arkaroola~Mt Painter the Spriggs say of Thomas:4

Mt Painter, South Australia.

He will go down in history as the person who in 1944 correctly predicted the discovery of major sedimentary uranium deposits out under the plains from Paralana Hot Springs. Exoil NL proved significant uraniferous accumulations in brown coal in this situation, including the ‘Beverley’ and related deposits.

Thomas's own letters record his feelings of those early days. Again in 1967 he wrote:

On geological camps, led by Mawson, I came to love all this upper Flinders Ranges country with a sort of ‘intoxication’ which has never left me, and has, indeed, extended much further afield. I often burn Callitris pine sticks at home here now as a sort of incense to recall unerringly all those happy days of enthusiastic geological ‘adventure’ (for such it was).

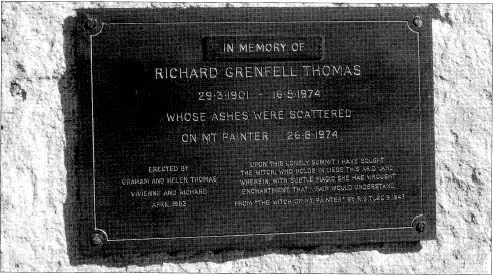

After his death in 1974, Thomas's wishes were carried out and his ashes scattered over Mt Painter in the ranges he loved so well. The following lines from ‘The Witch of Mount Painter’, a sonnet composed by Thomas, are inscribed on a plaque erected to his memory on the ‘Ridge-Tops’ road near Mt Painter in South Australia:

Plaque erected to the memory of R.G. Thomas on the ‘Ridge-Tops’ road, Mt Painter.

Upon this lonely summit have I sought

The witch who holds in liege this arid land

Wherein, with subtle magic, she has wrought

Enchantment that I fain would understand

During his lifetime, Thomas was to make an immense contribution, not only to the Australian minerals industry, but to its livestock industry as well.

After graduating BSc at Adelaide University, Thomas worked for a period with two companies — Radium and Rare Earths Co. and Australian Radium Corporation. The two groups operated at Dry Creek near Adelaide treating minerals from Radium Hill,5 near Olary, SA, and Mt Painter to recover uranium, radium, vanadium and scandium.6

In 1928 he joined the CSIR Division of Animal Nutrition in Adelaide. There the breadth of his geological and mineralogical knowledge and his almost intuitive understanding of biometallurgy became manifest when he pointed the way to the solution of ‘coast disease’ — a wasting disease afflicting sheep grazing on coastal plains of South Australia. Similar wasting diseases occurred in many parts of the world. It was known that coast sheep commonly suffered from anaemia with a gross lack of red blood cells. Thomas was surveying some areas affected by coast disease.7 From his geological knowledge he believed that the regions where coast disease occurred would be deficient in trace elements. He was also aware from the literature that dosing rats with cobalt induced in them an excess of red blood cells. He suggested that animals with coast disease might suffer from a deficiency of cobalt in their diet. Thomas's suggestion was subsequently proved to be correct, but his contribution to the solution of the problem remained unacknowledged until 1972 when Eric Underwood8 wrote ‘The Cobalt Story’. In this paper Thomas is given full credit for his contribution to the solution of the problem. This unsolicited acknowledgment gave Thomas great satisfaction during the last years of his life.

While at the Division of Animal Nutrition, Thomas discovered a remarkable occurrence of monazite in an old abandoned mine at Normanville, south of Adelaide. In one of his last letters to a colleague he recalls that he carried on his back literally hundredweights of this mineral monazite — the main source of the so-called ‘rare earths’. In the laboratory, after normal working hours, he set about extracting these rare earth compounds.

The excitement of seeing the gradual emergence of so many, often brightly coloured, compounds as the hundreds of fractional cr...