![]()

1

THE COLD, BARREN LAND WE CALL ANTARCTICA

It’s not getting to the pole that counts. It’s what you learn of scientific value on the way. Plus the fact that you get there and back without being killed.

Admiral Richard Byrd, Alone, 1938.

Antarctica – a word that conjures up feelings of bitter cold, sounds of howling gales, and visions of alien, barren landscapes – the desolate continent at the very bottom of the world. It has been uninhabited and unknown for most of human civilisation – a terra incognita until the 19th century. Poignant stories of human survival, bravery and death punctuate its early history of exploration. Sir Douglas Mawson dubbed it the ‘home of the blizzard’, a title well derived from his meticulous weather recordings which demonstrated that his base camp at Cape Denison had the highest average wind speeds of anywhere on Earth.

Antarctica has the coldest climate recorded on Earth, with extremes as low as –89°C. Today, almost nothing at all lives on the vast expanses of its ice-bound surface. Nearly all the continent is permanently covered by ice and snow, with mean annual surface temperatures hostile to life of any kind apart from a few organisms that can survive in just about any conditions imaginable. Near the edges of the continent life abounds in and around its biomass-rich, icy ocean waters, yet much of this life is ephemeral. The penguins and seals that come to feed during the warmer, summer season are mostly gone by winter, except for some well-adapted, extremophile species, such as the emperor penguin.

Yet Antarctica today is no reflection of what it once was. The evidence for this story is written by the fossils in its rich geological history. The plot is mysterious and unexpected; there is murder on a cosmic scale as global mass extinctions are caused by killer meteorites, and sudden shifts in climate that wipe out high proportions of life. Integral to all of this is the movement of continents and the formation of supercontinents. Antarctica has, for 99 per cent of its geological life spanning 3.8 billion years, been located within the hub of the various configurations of the ancient supercontinents known as Rodinia, Pangaea and Gondwana.

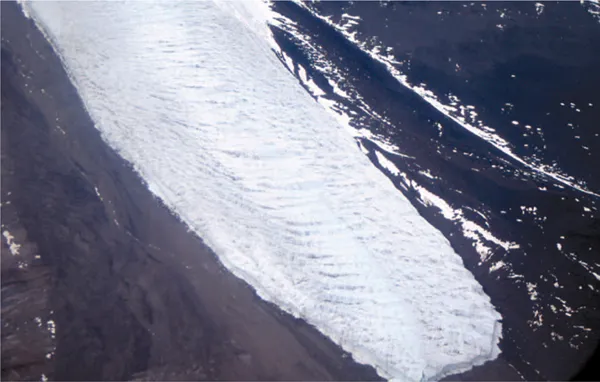

Rock outcrops adjacent to the Skelton Glacier, East Antarctica. Photo: Jeffrey Stilwell.

The story told by Antarctica’s diverse fossil record reveals that it was not always a lifeless continent locked in ice, but has been home to a great pageant of life through time. Its ancient, fossil-rich rocks reveal evidence of previous warmer climates – from the 250-million-year-old coal seams that run through the Transantarctic Mountains – part of the largest coalfields in the world – to the relatively recent non-fossilised wood from forests that grew on the flanks of the Transantarctic Mountains, only a few million years ago. Indeed, Antarctica was once rich in biodiversity, with ancient forests, huge dinosaurs, strange mammals and killer birds. The continent played a pivotal role in the migration and distribution of nearly all life in today’s southern continents.

The astounding fossil record shows that Antarctica – once the central landmass of the supercontinent of Gondwana – is really the key to understanding the evolution and biogeography of most of the living fauna and flora on all the major southern hemisphere landmasses today: South America, Africa, Australia, and the New Zealand microcontinent (‘Zealandia’). As we search further back in time, other landmasses, now subsumed within greater Asia, such as India, parts of China, South-East Asia and the Middle East, even part of the North American continent, were also in contact with Gondwana. Some of these regions still bear the distant biological imprints from this ancient geological alliance.

The fossil record of Antarctica shows us why we have southern beech forests in Australia and New Zealand, how dinosaurs were able to walk to every continent on Earth, and where and how the largest animals on the planet, the great baleen whales, may have evolved. Antarctica’s prehistoric record is also a tale of great tragedy. All that we have discovered from the decades of fossil hunting comes from a very small percentage of accessible rock around the periphery of the continent and in the mountainous regions that poke up through kilometres of ice. We see the demise of the expansive forests and the growth of the immense ice sheets that currently lock up nearly 70 per cent of the planet’s fresh water (and 90 per cent of its ice). The implications of these events continue to have a direct bearing on the global climate and the fate of most of Earth’s living ecosystems.

§

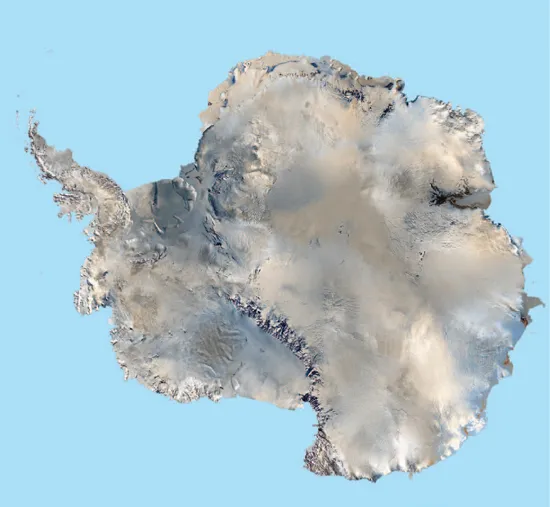

Antarctica is the fifth largest continent on Earth, covering approximately 14 million square km (5.4 million square miles), an area that is one-third larger than Western Europe, about 1.5 times the size of the United States of America, and comparable in size to all of South America. More than 98 per cent of Antarctica is covered by an ice sheet, which is about 5 km thick in some places. This makes Antarctica the world’s highest continent, with an average relief of about 2.3 km above sea level. Many fossil secrets inaccessible below the ice will remain that way, until (or if) in some distant time global warming unlocks long-frozen fossil treasures.

The continent is divided into the vast, flat polar plateau covered by the ice sheet, and the various mountain ranges, the largest being the Transantarctic Mountains which run right across the continent, dividing it into two greatly contrasting parts, the East and West. The Transantarctic Mountains extend from the north-western corner of the Ross Sea to the south-western corner of the Weddell Sea. The tallest mountain range is the Vinson Massif in West Antarctica, reaching nearly 5 km in height.

Less than two per cent of the area of Antarctica has rock exposures available for the geologist to study. The ice sheets bury nearly all of the topographic features of the continent, apart from the coastal outcrops and mountain peaks – known as nunataks – that poke up through the ice sheet in mostly inaccessible areas.

The Wright Valley glacier, Dry Valleys, Transantarctic Mountains. Photo: Jeffrey Stilwell.

Antarctica from space. Courtesy: NASA and dave pape.

Most of the world’s fresh water, approximately 24.5 million cubic kilometres, is currently locked up as ice in Antarctica. The East Antarctic ice sheet, which overlies a stable cratonic block of continental crust, covers 75 per cent of the area of the continent and it contains 80 per cent of Antarctica’s ice by volume. The West Antarctic ice sheet is far less stable as it covers part of the Antarctic Peninsula and a series of islands and embayments, and unites four land units each with a complex geologic history. There are also two large frozen fields of permanent ice floating atop the inlets of the Ross Sea and Weddell Sea on either side of West Antarctica – the Ross Sea Ice Shelf and the Weddell Sea Ice Shelf. There is also the Amery Ice Shelf in Prydz Bay.

Deep waters flow between these land units and the West Antarctic ice sheet, which is a floating ice mass and is held in place by great mountainous peaks. While the current glaciated state of Antarctica commenced some 34 million years ago, the ice in the ice sheets is not that old either, the most ancient being only one million years old – a mere blink of a geologic eye.

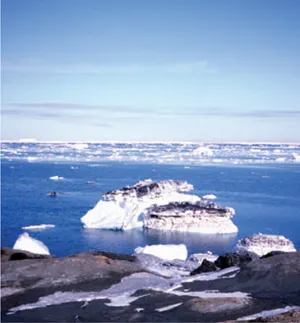

Deep blue and blinding white, the Ross Sea Ice Shelf breaks up in the austral summer. Photo: Jeffrey Stilwell.

Sea ice covers much of the waters surrounding the continent for most of the year. Ice flows bring sheets down from the high ground of the continent to sea level. This moves across the sea ice, before calving off into icebergs when it meets warmer water. The ice flows away from the highest points of the continent towards the sea on all sides. One would not think that ice itself flows, but it does due to its plastic nature. At the bottom of the thickest ice sheets plastic deformation takes place in the ice due to immense pressure from above. This makes the ice flow more easily over the bedrock of the continent – hence the reason for the unstable West Antarctic ice sheet.

The ice that is lost to the sea becomes replenished over time by snow inland. If the Antarctic ice were to thaw out entirely, the seas of the world would rise approximately 67 metres. The removal of the ice sheets would reveal a smaller Antarctic continent of around seven million square kilometres.

The break-up of sea ice during the austral summer enables ships to deliver supplies and allows tourist vessels to enjoy the splendour of the deep south. Photo: Jeffrey Stilwell.

Mt Erebus (3794 m) the world’s southern-most active volcano, is the largest of three major volcanoes forming the roughly triangular Ross Island. On the far left is Fang Ridge, representing an earlier crater wall, and behind is Mt Terror. Mt Erebus was erupting when first sighted by Captain James Ross in 1841. Since 1972 there has been continuous lava-lake activity, punctuated by occasional strombolian explosions that eject bombs of lava onto the crater rim. Photo: Jeffrey Stilwell.

The emperor penguin, Aptenodytes forsteri, the world’s largest and heaviest penguin, can grow to more than a metre in height and lives more than 40 years. Photo: Jeffrey Stilwell.

In the past, Antarctica was a hub of volcanic activity, and even today there are still a few active volcanic centres, such as Mt Erebus on Ross Island, Deception Island in the South Shetland Islands Group, and Mt Melbourne on the west coast of the Ross Sea in Northern Victoria Land (which has not erupted for a few hundred years) and several others, which have probably erupted in pre-historical times.1

Antarctica is technically the world’s largest desert. It almost never rains, apart from the fringing islands near the Antarctic Circle, as most precipitation falls as snow. The atmosphere is very dry, continually desiccating the landscape and any living organisms on it with savage winds. Visitors to Antarctica must drink water constantly to keep dehydration at bay. The climate is not very predictable, and random storms called ‘blizzards’, which can last as long as ten days, happen throughout the year, fuelled by the gravity-fed, intensely bitter, katabatic winds blowing out and rolling off the elevated polar plateau. The seasons fall neatly into the continuous 24-hour daylight of summer, the perpetually dark night of winter, and the relatively brief autumn and spring twilights. The mean monthly temperature at the South Pole in summer is –30°C and in winter it is –54°C. At Vostok Station, the temperature registered an inhospitable –89.6°C in August 1983. As far as humans are concerned this may as well be absolute zero! During summer in the Dry Valleys, the temperature can rise as high as 10°C.

For four months of the year, Antarctica is in total darkness. Due to the absence of pollution, nights in Antarctica are breathtakingly clear with innumerable twinkling stars, along with bright planets and shooting stars or asteroids. These events remind us about the vastness of time and space. If one is lucky, one can witness a natural light show called the aurora australis (or ‘Southern Lights’), which can shimmer away in the Antarctic night sky, mesmerising and amazing those who view this spectacular phenomenon. Even during the short summer season the water under the ice receives less than one per cent of the surface sunlight. The temperature of the water is be...