![]()

1 Biology

Mistletoes are a diverse group of parasitic plants found throughout the world. Like mangroves and succulents, mistletoes are a functional group, defined by the way they grow. Thus, rather than a single plant family, mistletoes include representatives of several families, and their distinctive parasitic habit has evolved independently on multiple occasions. These complex origins and global distribution have led to some confusion, with many people familiar with European mistletoe being unaware of the hundreds of mistletoes found beyond Europe, and many Australians assuming that mistletoe was introduced into this continent. In this chapter, these misconceptions are dispelled and a summary of our current understanding of mistletoes’ origins, diversity and life history provided. Having clarified what mistletoes are, various other kinds of plants that live within the canopy are distinguished. Global patterns of diversity and distribution are summarised for the main mistletoe groups, as well as current ideas about their origin and early evolution. Moving closer to home, the biogeographic patterns of Australasian mistletoes are discussed, comparing Australian mistletoes with near neighbours New Guinea and New Zealand, and evaluating possible explanations for the absence of mistletoe from Tasmania. Finally, the life cycle of mistletoes is described, detailing the complex set of processes that allow one plant to depend entirely upon another.

What is mistletoe?

A young girl once described mistletoes to me as ear-rings for gum trees. While describing perfectly the teardrop-shaped clumps of dense foliage at the edge of eucalypt crowns familiar to many Australians, this description does not apply to all species and a more inclusive definition is needed. Mistletoes are obligate parasitic plants – instead of obtaining nutrients and water directly from the soil through roots, they take them from other plants. Over 4500 species in 20 families of flowering plants have adopted a parasitic habit, looking like regular herbs, shrubs or trees above ground while tapping into the roots of nearby plants below ground. Relying on their hosts for all of their water and nutritional needs, most parasitic plants manufacture their own carbohydrates using photosynthesis. This growth habit is known as hemiparasitism (half parasitic) and distinguishes these green plants from various ghostly plants with no chlorophyll that rely on their host plants or host fungi for all of their needs (holoparasites). Unlike most hemiparasites, mistletoes attach to their hosts above ground, thereby freeing them from the soil completely. Several other parasites have adopted an aerial habit, but mistletoes are distinguished by their growth form – they are shrubby, often woody plants. So, mistletoes can be defined using three words – shrubby aerial hemiparasites – and this definition sets mistletoes apart from all other plants, both within Australia and worldwide.

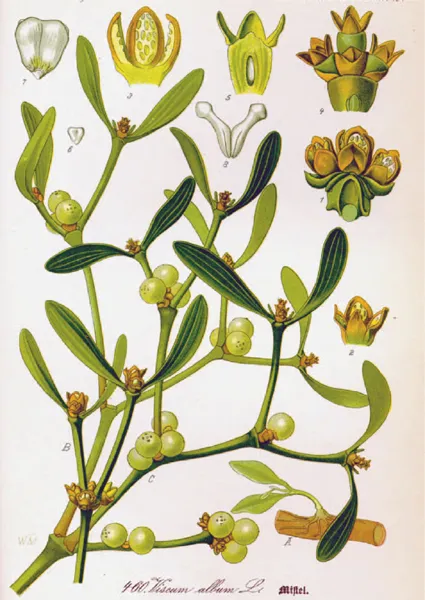

The mistletoe Viscum album from otto Wilhelm thomé’s Flora von Deutschland Österreich und der Schweiz (Flora of Germany, Austria and switzerland) 1885.

Derivation of the word ‘mistletoe’

Originally used to refer exclusively to the single species in Western Europe (Viscum album), the word mistletoe dates back to the Anglo-Saxon, but the exact derivation is debatable. Some linguists suggest the word can be traced to Misteltan, coming from two Old German words: Mist (dung) and Tan or Tang (twig), referring to the way mistletoe seeds are dispersed by birds. An alternative suggestion is that the word came from Mist the Old Dutch word for bird lime – a sticky glue-like substance derived from various plants including Viscum album smeared on twigs and branches to catch small birds. A third option is a combination of Tan with another Old German word, Mistl (different), referring to the clear difference between parasite and host (especially in winter, when the leafy mistletoe contrasts with the bare twigs of its deciduous host). Regardless of its derivation, the word has been in use since the 14th century.

Using this definition, we can consider other kinds of plants that are often confused with mistletoes. A distinctive plant found throughout the world is dodder (many species in the genus Cuscuta) and the unrelated, but remarkably similar, dodder-laurels (Cassytha species) – twisting vines that form tangled clumps of yellow to lime-green tendrils within the branches of their host plants. Although they are hemiparasitic and attach to their hosts above ground, these herbaceous vinelike plants have no woody tissues and never adopt a shrubby habit, so are not regarded as mistletoes. The branches of forest trees – especially in the tropics and other high rainfall regions – are often covered with smaller plants, including mosses, liverworts, ferns, orchids and a range of other flowering plants. These plants, known as epiphytes, are not parasitic and take nothing from the tree – they just grow upon the bark and use the tree to grow above the ground where there is more light and greater access to pollinators and seed dispersers.

The twining parasite dodder Cuscuta pubescens.

Strangler figs represent a particular kind of epiphyte, which begin growing high in the canopy, then send down roots as they grow larger, eventually out-shading the original tree. Again, this is not parasitism but, rather, a novel strategy to gain a competitive advantage in dark closed-canopy forests.

An epiphytic bird’s nest fern Asplenum australasicum.

A strangler fig Ficus sp. – not a mistletoe.

Aside from epiphytes, there is one final kind of growth that can be confused with mistletoes. A range of mites, wasps and other insects lays their eggs inside plant leaves and stems, inducing the formation of tumourlike growths to nourish their developing larvae, which are known collectively as galls. Occasionally, these galls can change the branching pattern of the affected plant, leading to densely branched nestlike structures called witches’ brooms or just brooms. Likewise, mutations or viral infections can arise inside plants leading to fasciation – broom-like structures within the canopy. Although these clumps can look a lot like mistletoes, they are not – they are just abnormal growth of the tree or shrub itself. In the northern hemisphere, a group of diminutive mistletoes known as dwarf mistletoes (Arceuthobium spp.) can induce the growth of brooms on infected conifers, but this group does not occur in Australia and broom-formation is not associated with any native mistletoe species.

A witches’ broom in a Blakely’s Red Gum Eucalyptus blakelyi. This mass of densely branched foliage is composed entirely of eucalypt tissue and is not a mistletoe.

A root-parasitic native cherry Exocarpos aphyllus.

The parasitic habit

Mistletoes attach to their host via a specialised organ called a haustorium. Resembling the woody holdfast used by kelp to attach to the ocean floor, this structure serves two purposes – anchoring the mistletoe and tapping into the sap of the host plant. Once the mistletoe has attached to a branch, the water and dissolved nutrients in the xylem vessels flowing to the growing, leafy end of the branch are intercepted. The branch downstream of the mistletoe typically withers and dies while the other end of the branch (leading to the mistletoe) swells at the junction with the parasite, often growing into a club-like shape. This union between tree and mistletoe can become quite large, often persisting on the tree long after the mistletoe has gone. Known as wood roses or rosarios, these growths are highly sought after by wood turners and carvers and form the basis for local crafts in various regions of the world.

A young Box Mistletoe showing the developing haustorium – the connection between parasite and host.

Detail of the connection between host (below) and mistletoe (above).

Carved lizards on elm wood haustoria from South-East Asia (from author’s private collection).

Rather than actively pumping water, mistletoes use a combination of passive mechanisms to draw water from the hosts’ xylem vessels. Unlike other plants, the leaf pores (or stomata) used by mistletoes for gas exchange remain open day and night, even in hot or dry conditions when most plants close their pores to minimise water loss. This continuous transpiration sets up a strong moisture gradient between mistletoe and host, allowing the mistletoe to draw water continuously from the host. In contrast, the host uses a variety of strategies to conserve water, including reducing water flow to outer branches during dry or windy conditions. Mistletoe plants are typically more sensitive to water shortages than their hosts, especially in arid areas, so prolonged droughts can lead to widespread mistletoe mortality. In addition to water, mistletoes also take dissolved nutrients from their host plants, with the high transpiration rates leading to elevated concentrations of a range of nutrients (especially phosphorus, potassium and other metals).

While further assisting in water transport, mistletoes can also use this mechanism to concentrate various salts in their leaves. This strategy is most clearly displayed by several mistletoe species that grow primarily on mangroves in northern Australia (such as the Mackay Mistletoe Amyema mackayensis). As salt concentrations increase, the round fleshy leaves become progressively thicker before eventually being shed, allowing the plant to rid itself of excess salt. Along with nutrients and water, there is some evidence that other chemicals circulating in host plants are absorbed by mistletoes, including toxins and hormones. The popular garden plant Oleander Nerium oleander is known for its high toxicity and occasionally hosts several Australian mistletoes, with anecdotal reports of the mistletoe plants acquiring dissolved toxins. Rather than a two-way exchange, the flow is one way only, and there is no evidence of any transfer from mistletoe back to host. Further details of interactions between mistletoes and their host plants are covered in Chapter 3.

The mangrove specialist Mackay Mistletoe showing the fleshy round leaves in which excess salt is stored.

Mistletoes around the world

There are over 1500 mistletoe species currently recognised. They are found wherever woody plants occur (i.e. absent only from high mountains, polar regions and the driest deserts) and the large number of species recently described indicates that there are more awaiting discovery. In addition to tropical rainforests and deserts, mistletoes can be found in most forests, heathlands, woodlands and mangroves on all inhabited continents. Mistletoes are also found on most oceanic islands, including those remote islands known for their distinctive plants and animals that evolved in isolation. Thus, Madagascar, New Zealand, the Hawaiian archipelago, the Azores, Maldives, Canary Islands, Comoros Islands and Galapagos Islands all have mistletoes, including many highly restricted species found nowhere else. One notable exception is Tasmania – an intriguing pattern considered later. As with most other groups of organisms, mistletoes achieve their highest diversities in tropical regions. Thus, compared with just four species found in all of Europe, 179 mistletoe species are known from Africa, with similar patterns found in Asia and the Americas. Although most mistletoes infect trees and shrubs, columnar cacti in South America and giant euphorbs in southern Africa have their own mistletoes – bizarre plants that live entirely inside their host, detectable only when their flowers emerge directly through the succulent tissue of their hosts.

Mistletoe origins and relationships

Given their unique way of life, mistletoes were long considered to represent a single family of plants arising from one shared ancestor. Current opinion is that, although mistletoes are related (arranged within the Santalales or Sandalwood division), the aerial-parasitic habit arose independently five times – in all cases from root-parasitic ancestors. Currently, mistletoes are divided among four families: the feathery mistletoes (Misodendronaceae); sandalwoods (Santalaceae); showy mistletoes (Loranthaceae); and the Christmas or ‘true’ mistletoes (Viscaceae). The first group is an ancient lineage represented by a single genus of 10 species restricted to southern beech (Nothofagus spp.) forests in southern South America – their common name referring to filamentous wind-dispersed fruits borne in downy tresses. Although the sandalwoods are best known as root-parasitic trees with highly prized aromatic wood, several lineages within this group have developed other growth habits, including stem parasitism. These 43 species are found in tropical forests of South-East Asia and Central America and represent some of the most poorly known mistletoes. All remaining species fall within the other two families, both of which have a global distribution. Importantly, these families – which represent the archetypal mistletoes – are not one another’s closest relatives and they display several noteworthy differences arising from their long-separated evolutionary histories.

A fruiting Quandong Santalum acuminatum. Although most members of the Sandalwood family are root-parasitic shrubs and trees, several groups have become aerial parasites, including one species found in Cape York.

Root-parasitic mistletoes – a contradiction in terms?

The showy mistletoe family contains three species of root parasites – corresponding to the three earliest surviving branches of the family’s evolutionary tree – suggesting that the aerial-parasitic habit evolved ...