![]()

Chapter One

Thoma Çaraoshi Joins the Party

and Sells the Sheep

In Albania everything happens over coffee. Luljeta introduced me to her father-in-law, Thoma, after I mentioned over coffee that I was interviewing people about life in the communist period. Thoma had recently moved to Tirana to live with his son’s family, and we set our first meeting for Monday at 9 a.m. That first Monday, Eda and I walked from our homes in Ali Demi, a suburb at the foothills of Dajti Mountain, to Thoma’s neighbourhood behind the city lake, which was land cleared and newly forested with 14-storey apartment blocks. It was my first meeting with Thoma, and Eda’s first interview as my research assistant, so we arrived at the designated corner feeling nervous and excited. Luljeta was speaking on her mobile phone. Thoma had not returned home to meet us as planned.

We walked the local streets and enquired at cafés, where baristas told us that Thoma had been spotted drinking his morning espresso, having his hair cut, in conversation with the local dentist, and then strolling in the direction of the city. Back at home Thoma’s son reported that he had not returned, so we sat in the café across the road from the house to wait. Luljeta’s father waved from the balcony of his nearby flat to show that he understood where to find us. Luljeta was dismayed. Thoma was a stickler for punctuality against the time-bending mainstream of Albanian culture. Perhaps he had forgotten and this was the first sign of old age appearing at the most inconvenient moment? Perhaps something had happened to him?

While we waited, Luljeta reminisced about her childhood in the 1980s, the hungriest years of the communist period. She marvelled that she’d been convinced by the Party’s claims that Albania was the richest country on earth. The woman running the otherwise empty café overheard our conversation, introduced herself as Mindie, and joined in with her recollections of life in Kukës, a city in the north, where she lived before the dictatorship fell until 1992. Mindie was the same age as me, but she looked like she’d lived through a lot more. She told us that she was one of eight children from a poor village outside Kukës, and they had picked mountain blueberries in summer to supplement their parents’ meagre income from hard agricultural labour. The blueberries were sent for sale in Tirana for medicinal purposes. One of her brothers secured a better-paid job in the mines, dangerous work that left the men chronically ill with back pain and digestive disease. Mindie spoke evenly and fast in a soft voice, as if she had the words long prepared and feared that the moment to share them was too brief. Her mother sat a few tables away, dressed in a traditional long black skirt and apron with a white cotton scarf tied around her head. Mindie told us that her eldest sister had cared for the children at home while her mother worked long hours in the co-operative. One night, the kerosene of the lamp spilt on her sister’s body in the bathroom and she was badly burnt. For shame of her nakedness she did not call to the children for help, and she died soon after they found her there the next morning.

While Mindie spoke, her mother lamented a single sentence with increasing volume: “They treated us like dogs in that time!” She pulled herself up with one hand gripping the table and the other her walking stick, and hobbled over to us. She asked my name, rested her stick against the table, and held my face in her hands. She kissed my forehead and focused her blue eyes on my own. “They treated us like dogs,” she told me. Then she turned and shuffled out of the room.

We sat in silence. After a few minutes, the door opened and a tall, well-built man dressed up in a shirt, tie, waistcoat and jacket stepped inside. “Hello! I am Thoma,” he boomed, smiling. Mindie jumped back to her waiting position, Eda and I stood to greet Thoma, Luljeta left for work, and Thoma began asking us questions. As is usual for first meetings between strangers, especially for older generations of Albanians, Thoma asked Eda what her family name was, where she was born, and where both sides of her family had lived before the demographic movements under the socialist regime. From these questions, complex information about a family’s social and political position before, during, and after the socialist period are deduced and applied to individuals. Connections are thus established or broken. Eda’s father was from the south, and Eda grew up in the same small city of Delvina where Thoma spent his childhood before World War Two. Thoma declared Eda his cousin, while I fit his category of the single woman far from home. At every meeting he enquired as to the health of my family and whether my apartment in Tirana was warm, and he was gentler with the topic of where to find me a husband than he was with Eda.

We met every week, and Thoma was never again a moment late or confused as to any arrangements. As the weather warmed into spring and then the scorching summer, we met earlier in the mornings, and Thoma led us to cafés further afield, where he was known as a regular patron. Impeccably dressed, and seeming closer to 60 than his 80 years, Thoma proudly introduced us as his “interviewers from Australia” to the wider world of retired men spending time with a coffee, a stiff drink of raki, and their stories. That first meeting had been a ruse of fashionable lateness on his part, effectively heightening the curiosity of the entire neighbourhood as to his whereabouts and the foreigners eager for his presence.

Thoma understands people and it became clear that he enjoyed talking about the past precisely because it troubled him; the ideological contradictions and the question of how he survived could not be easily explained. His stories of finding work and raising a family through waves of political purges were not to be told just once, but perhaps as many times as they had played out in his mind since their occurrence, and Eda and I loved listening. Using language and cultural references grounded in the ethnic diversity of pre-war Southern Albanian society, Thoma’s story took us to many worlds and ways of being in these worlds. From his childhood in an ethnic Vlach shepherding family, through the Second World War, and through the decades of communist rule.

* * *

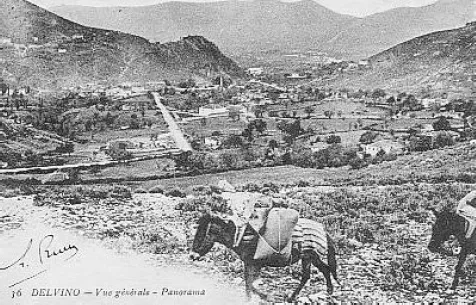

Thoma was born in 1932 at his family’s home in Delvina, a village separated from the city of Saranda on the Ionian Sea by a single ridge of mountains. Thoma was the third of nine boys and one girl born to his Vlach family, the ethnic minority of shepherds and traders found throughout the Balkans. Vlachs speak Aromanian, which derives from fifteenth-century Romanian language, with more Greek than Slavic-integrated vocabulary. Thoma’s grandfather, Mihal Çaraoshi, had migrated to southern Albania with his wife and five children after the First World War. The entire family worked and lived together, and as his grandfather had trained to be an Orthodox priest in Greece, he taught his grandchildren to read and write in Greek language. They spoke Aromanian at home, and attended Albanian primary school in Delvina.

The family tended their flock of sheep and produced dairy products for local villages. In summer they grazed the sheep in the mountains, walking the hills and valleys between Delvina, Gramoz, Skrapar and Mount Tomorr, to the city of Berat. The journey from Delvina to Tomorr took 20 to 30 days – sheep are slow moving animals – and the family slept outside in the stans, lean-to, tent-like structures on the hillsides built to protect the sheep from harsh weather, or in inns that catered for shepherds and travellers. The family all worked to milk the sheep twice a day. When the weather was warm, the milk curdled into soft cheese within an hour, and when it was cold they warmed the milk to make the cheese, draining it in cheesecloth hung in the huts along the route and cutting it to sell in the villages and towns they passed on the journey. The cheese sold so quickly that it didn’t need to be salted. The family built wooden huts in the mountains where they could leave the cheese-producing equipment safe in winter while they stayed with the flocks in Delvina and Konispol, and the children went to school.

Thoma’s father, Mitro, was one of many Albanians who travelled to Italy to modernize his trade in the interwar period. Between 1930 and 1939, Mitro produced cheese with a small American company in Italy, returning every June with his earnings, better production techniques and material culture such as cutlery and glassware to improve the family’s living conditions. Mitro invested his earnings in livestock, and by the time that Thoma’s grandfather passed away in 1939, the family owned 2000 head of sheep, producing 500 litres of milk and many barrels of cheese per day. Hired shepherds took care of the sheep, and the family lived very well. “Even fish comes to the mountains if you have the money to pay for it,” Thoma often said in reference to this time.

Mussolini invaded Albania through the port of Durres on 7 April 1939, and moved south to invade the Kingdom of Greece in October 1940. After the war began, Thoma’s father stayed in Delvina with his family and the livestock. Albanian villagers formed partisan groups to fight Italian and then German occupation. The two major partisan groups in the south were the Balli Kombëtar (meaning National Front, known as the Ballists, formed in October 1939) and the communists from 1941. Both groups hid in the mountains, supported by or stealing from local residents, and villagers of the time didn’t necessarily see the Ballists and communists as ideological opponents, but rather as both fighting for Albanian independence from foreign occupation. In an early diplomacy lesson, Mitro referred to the sheep stolen by partisans as having been “eaten by war.” The sons of the family were thus taught that there were two groups of active partisans in the area, and that men from both sides stole livestock to eat. Mitro was a member of the communist party, and two of his sons fought with them, one losing his life. Thoma, 12 years old at the time, carried messages for partisan units between the villages and towns, escaping suspicion by walking with a donkey laden with wood.

In April 1944, the National Liberation Army (communists) held the Congress of Permet, where an administration was appointed to prepare for post-war Albanian self-government. Thoma and his donkey carried boxes of unknown content to the village of Frasher under the guard of two partisan fighters; he was trusted because his family was known to support the partisan efforts. The communists recognized Vlach families, who had cabins in the highlands, as valuable to the partisan war, and they were treated relatively well by the communist regime until the early 1950s, when their linguistic difference and strong family units were construed as potentially treasonous to Albania. Still, during the war the Çaraoshi family worked to remain on good terms with all Albanian partisans, and they even hid a general of the National Liberation Front in a cave in the mountains after his unit lost a battle. Thoma took him food twice a day for five days until the German offensive withdrew, and this general, who went on to be a powerful Party member in Tirana, proved a vital contact to have when the regime began to persecute the Vlachs and Greeks in the mid-1950s.

Delvina, Italian postcard, Interwar period.

Mount Tomorr viewed from Berat, 2012.

The National Liberation Front claimed to win what they called the War of Liberation in Albania, and they established a provisional government in Berat in October 1944 with Enver Hoxha, a tall and sturdy young partisan from the southern city of Gjirokastër, as prime minister. In the elections of December 1945, the National Liberation Front’s successor party, the Democratic Front, won 93% of the vote. Hoxha ruled, primarily by imprisoning and executing all potential rivals, until his death in 1985. In 1945, Enver Hoxha and his partisan peers cut fine figures and presented an agenda that appealed to many young people. They offered an ideologically organized infrastructure for all to participate in a utopian nationalist movement for modernization.

What could be wrong with working together to develop Albania as an independent state, reorganizing production, education and society with a centrally administered plan for the best outcome for all? For the majority of Albanians who owned just small plots of land and who hadn’t had the chance to gain an education, the Democratic Front’s nationalisation of land and wealth made sense. Those who were politically astute and experienced, and even normal working people who owned property, land, and businesses, quickly understood that they could not avoid the progressive taxation and then seizure of their wealth. Many were branded enemies of the state, as bourgeoisie and kulaks. Enemies were found in every region, even if those punished as kulaks were in fact not much richer than their fellow peasants. Those named enemies were executed or used as imprisoned labour forces. This forced labour completed massive modernization projects such as the draining of the mangroves for arable land in Maliqi and Durres at the cost of many lives, while the Party took the praise for “development” of agriculture and infrastructure. The punishment of kulaks and their families was an example to others of what lay on the opposite side of enthusiastic support for the party, and these constantly “unmasked” enemies provided a shifting focus to maintain anxiety amongst the people.

Thoma’s father Mitro noted the communists’ overarching discourse of revolution by arms and without dissent, and he remained a member of the Democratic Front. He did not ask for compensation for the livestock “eaten by the war,” and he explained to his sons that there was a difference between consistent moral law (as in the Bible and the Koran) and the harsh laws of ever-changing rulers. As Thoma still says to explain post-socialist politics, “If you break the law of the state, the law groans, and its owner seeks to punish those who have caused it to weep.” In recounting stories from throughout his life, Thoma would often use this metaphor to make meaning of the arbitrary nature of the law, and the cruelties of those who acted and still act in its name.

The teenage Thoma, however, saw the triumphant, young, and strong men of the communist movement as harbingers of a luminous future, and it was only through the trials of the next twenty years that he came to understand his father’s wisdom and see political power as an arbitrary and shifting force. At the end of the war, Thoma saw Enver Hoxha, who marched into Tirana with his armed comrades, as “the new king,” and he decided to stand with them. Considering his intelligence, energy, and his family’s good standing with the Party, in 1951 Thoma was admitted to military school in Tirana for a year of ideological and tactical studies. Thoma travelled to Tirana with the energy and hope of a young man who saw the way to help rebuild Albania.

Enver Hoxha emphasised the vital role of youth to lead the country to its glorious destiny, and he blamed the poverty of agrarian society on the ruling classes, the monarchy, and previous bourgeois governments. The Democratic Front promised education, employment and remuneration to all, and relied on full social participation to staff the schools, agricultural co-operatives, and factories that would industrialize Albania. In the late 1940s and throughout the economic developments of the 1950s, Enver Hoxha presented the socialist movement as a collective where youth bound by the blood losses of war could sacrifice personal interest for national development. The power of a shared goal to make Albania strong equalized and mobilized the post-war youth, and they learnt about socialism in ideological classes and through propaganda. While Thoma was from a beautiful part of the country abundant in food, other youth recruits in his classes shared their experiences of harsh living conditions and poverty, and Thoma understood the appeal of the promised life of plenty to those who were raised in poverty.

Thoma remembers that heady atmosphere – there was shared work, food, and travel for the groups of young, energetic men. The Albanian-Soviet alliance provided the possibility to travel to Moscow for education, and reassured all that independent Albania now had powerful and vast allies to defend the national borders from attacks such as those of the Italian and German occupations in World War Two. Thoma aimed to build socialism, join the Party and travel to Moscow for a diplomatic education. As his father had travelled to Italy before the war to support their family, he also planned to pursue opportunities abroad. Socialism made sense to Thoma. It was an honourable extension of his family’s ethic of hard work, meritocracy, and the inalienable bond of family to include the national Albanian family in which all could work and prosper.

After graduation in 1952, Thoma was sent to work as a Party Youth Secretary with the Fifth Division in Hoxha’s hometown of Gjirocastër...