eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

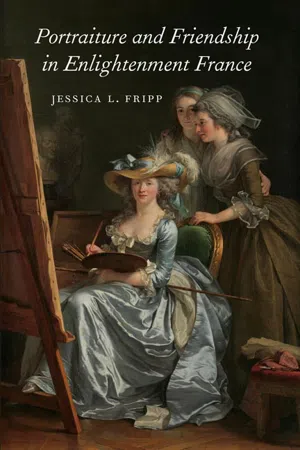

Portraiture and Friendship in Enlightenment France

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Portraiture and Friendship in Enlightenment France

About this book

Portraiture and Friendship in Enlightenment France examines how new and often contradictory ideas about friendship were enacted in the lives of artists in the eighteenth century. It demonstrates that portraits resulted from and generated new ideas about friendship by analyzing the creation, exchange, and display of portraits alongside discussions of friendship in philosophical and academic discourse, exhibition criticism, personal diaries, and correspondence. This study provides a deeper understanding of how artists took advantage of changing conceptions of social relationships and used portraiture to make visible new ideas about friendship that were driven by Enlightenment thought.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Portraiture and Friendship in Enlightenment France by Jessica Fripp,Jessica L. Fripp in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

FRIENDSHIP IN THE ACADEMY

THE 1648 STATUTES of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture made it clear that the bonds between the members of the newly formed institution were a primary concern. The ninth statute declared: “There will be close and friendly relations among the members of the Academy, there being nothing so antithetical to virtue as envy, malicious gossip and discord. If any should be incline thereto, and should be unwilling to amend after reprimand by an Elder, he shall be excluded from the Academy.”1

Versions of the same statement appeared in the revisions to the statutes in 1664 and 1777.2 Along with the mandate that Academicians maintain positive relations, the words ami (friend) and amitié (friendship) appeared frequently in the Procès verbaux, or minutes, of the Royal Academy’s meetings over the next 145 years. The diverse contexts in which friendship was employed reflect the many meanings it carried in early modern society. For example, in correspondences with foreign academies, the French Royal Academy referred to these institutions as “friends,” demonstrating that the Academy was connected to the broader European community of art-making, and mirroring friendship as a display of loyalty across intellectual communities and the Republic of Letters.3 As was the case for early modern academy members across France, the word ami appeared frequently in the eulogies for deceased Academicians, to highlight their moral qualities as a “good friend.”4

The word ami was also used in the lectures on artistic theory that opened the conférences, monthly meetings for the Academy’s members to discuss artistic questions.5 These lectures give a view into the Academicians’ ideas and theories about painting, which, as Christian Michel and Jacqueline

Lichtenstein point out, did not create the rigorous and strict system the nineteenth-century historiographers of the Academy passed on to art historians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The lectures avoided defining what might be the “perfect” artist or “perfect” work of art in any strict homogeneous terms.6 They did, however, offer examples of specific behaviors that would help artists attain an abstract idea of greatness.

Friendship was a theme that frequently arose in these lectures. In particular, those read by Antoine and Charles Coypel in the first half of the century made it clear that amity mattered to artistic creation just as much as a practical knowledge of color, space, and human expression did. The Coypels drew from the classical model of friendship described by Cicero and Aristotle, which emphasized virtue and claimed that friendship played an important role in both private and civic life.7 Virtuous friendship in private naturally extended into the public realm, providing political stability.8 Reliance on friendship was based in the belief in men’s rational choices and ethical behavior, and, as such, it was a part of civic life, inspiring individuals to sacrifice their personal desires to the needs of the greater whole.9 In contrast to love, friendship required sustained and controllable passions. By presenting the Academicians as virtuous friends in the model of Aristotle and Cicero, the Coypels promoted the stability of the Academy as a social body, justified its existence, and increased its social prestige.10 But as much as the Academy tried to maintain ideal friendship as a central feature of the institution, the development of a politicized—and more inclusive—public sphere called friendship’s role into question.11

The Academic ideal of friendship was most explicitly challenged by the clandestine criticism published in response to the Royal Academy’s exhibitions held in the salon carré of the Louvre, which were regularized in 1737. As Thomas Crow has argued, the success of the Salon exhibition and the art criticism it spurred ushered in a larger debate about who exactly made up the art-viewing public, what its role in artistic production was, and importantly, who had the right to speak for that public.12 Unofficial commentary on the Salon, particularly that which spoke disparagingly about the Academy and its artists’ works, was always contested. The Academy argued that the often-anonymous critics were not speaking to the Salon audience’s true desires. Despite the Academy’s attempts to stop criticism through censorship and the seizure of published pamphlets, the criticism reached its height in the 1770s and 1780s. It was at precisely that moment that critics began to use friendship to justify their commentary.

This chapter focuses on three key moments, roughly dated to 1712, 1747, and 1779, to examine the relationship between friendship and criticism, as discussed by both the Academy and its critics. The conférences relied heavily on three traditional cornerstones of friendship—disinterestedness, sameness, and masculinity—in defining the role of friendship in criticism, framing it as a social exchange restricted to individuals who possessed the sufficient knowledge about art to comment on it. This served to define Academicians and amateurs honoraires, patrons who were given membership in the Academy, as artistic authorities and as members of an exclusive community.13 Salon critics’ appropriation of friendship challenged the Academy’s authority by engaging with eighteenth-century questions about friendship, including discussions of virtue, amour-propre (self-love), gender, and friendship’s place in public life.

Antoine Coypel’s Épître à mon fils: Criticism and Ideal Friendship

On January 7, 1708, the history painter and future director of the Royal Academy Antoine Coypel read a poem dedicated to his son Charles at the Academy’s general assembly. The poem, Épître à mon fils, sur la peinture, was published that same year.14 On May 7, 1712, Coypel reread the poem at the Academy; according to the procès verbaux, the Academicians “unanimously begged Monsieur Coypel to continue the commentary that he started with the Letter in verse to his son, and wanted him to read it to the Company on meeting days.”15 Coypel complied, and over the next eight years he divided the poem’s 186 lines into twenty-one lectures on various subjects, which were read at nineteen different séances, or meetings, of the Academy.16 Coypel’s poem and the subsequent lectures it inspired covered a range of topics, from formal and technical aspects of artistic practice (such as color, drapery, and proportion) to theoretical ideas that resonated with those discussed in the conférences read previously by the theorist and amateur honoraire Roger de Piles.17

Along with practical discussions of painting, Coypel also presented substantial discussions of what might be called the morals and behavior of painters. His first three lectures, on July 2, 1712, focused on the three parties involved in the lifespan of a work of art: the painter (peintre); those who advise the painter (conseillers); and the spectator-viewer for whom the work is destined (spectateur). The discussions of the spectateur, as Lichtenstein and Michel note, introduced for the first time the idea of not merely a viewing public, but a critical public.18

From the outset, Coypel’s lectures suggested a close connection between friendship and criticism. The second one, “A Painter’s Advisers” (Les conseillers d’un peintre), corresponded to the sixth verse of Épître à mon fils—“But listen my son, to a father who loves you” (“Mais écoutez mon fils, un père qui vous aime”)—and focused on those who might help the painter to succeed, while also including discussions of “taste” (goût), who was qualified to judge works of art and how to do so, and bias (prévention).19 All three concepts were intricately linked to friendship as it was understood by the Academy. In the poem, Coypel’s ideas are framed as advice from a loving father to his son. The lecture that expands on the verse, however, clearly advises on friendship, not familial love. Slipping between friend and family would not have been counterintuitive in the early modern period, as kinship was often discussed using the language of friendship. From the medieval period through the eighteenth century, French law considered friendship synonymous with kinship; the phrase parents et amis referred to both relatives and friends in law codes. Catholic moralist literature similarly described parent-child relations in terms of friendship, not love.20

Coypel’s choice to move away from the bonds of blood points to a second, evolving form of friendship. The period during which this group of lectures was delivered coincided with the increasing prominence of the role of honorary amateurs (amateurs honoraires), which Coypel was keen to cultivate in order to bolster the social status of the Academy.21 The relationship between these patrons and Academic artists drew heavily on a language of friendship.22 This was an extension of earlier, seventeenth-century descriptions of “friendship” that delineated the relationship between patrons and artists, and helped to put order to political and social life rather than portray intimate relationships between men.23 As a number of scholars have noted, during the eighteenth century, artists and patrons began to socialize in unprecedented ways, which significantly altered traditional patron-artist friendships.24

Coypel’s conférences were, however, equally concerned with friendship between artists, and his discussion provided a baseline for how Academic relationships would be framed throughout the century. He began by claiming that an artist would be most inspired by advice that came from a friend: “The advice that we are given by the people with whom we know friendship surely makes more of an impression on us than that of others. For much self-interest enters in the desire to give advice. How many people persuade themselves to deserve all the honor of a work on which they have given a favorable critique, from which the same author himself would profit!”25 Coypel is intriguingly generic in his description of friendship in this quote; one must look for a person (personne) who knows friendship (amitié). While he avoids using the word friend (ami) directly, he clearly contrasts this type of individual with the unhelpful people who lack a principal element of friendship: disinterestedness.

People who offer advice outside of friendship should not be trusted, according to Coypel, because some of those individuals seek to profit from convincing others that a work has merit, or they enjoy the satisfaction of having others agree with them. A critic’s self-serving actions are especially dangerous—ultimately, the critic has little to lose compared to the artist himself: “Happenstance gives them the liberty to always criticize, it is introduced in society for the connoisseurs and the sole arbiters of good taste alone. As such the decisions no longer cost them anything; they make them even without seeing what they criticize and without examining it; simpletons listen to them; ignorant people admire them and the appalled artists are always the victims.”26 Eventually, an abundance of advice, often offered out of self-interest, becomes so tiresome for an artist that he might not accept any advice at all.27

Such a scenario could be frustrating for the painter. Happily, Coypel offered one test to help an artist determine if he was receiving appropriate counsel: “How easy it is to distinguish what friendship advises from what vain pride decides! The true friend praises in public that which can be praised and criticizes in private what appears weak or defective. The vain and sumptuous man lauds face-to-face and becomes cold or a ruthless censor when surrounded.”2...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Friendship in the Academy

- Chapter 2 Celebrating Celebrity

- Chapter 3 Re-Evaluating Rivalry

- Chapter 4 Friendship Abroad

- Epilogue

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index