![]()

![]()

Contents

Preface

1 Rumours of hope

2 Missionary disciples

3 Agents of mercy

4 Ending sexual violence and abuse

5 Ending human trafficking and slavery

6 Hope for prisoners

7 Resisting religious extremism

Epilogue: What makes us human?

Acknowledgements

Notes

![]()

Preface

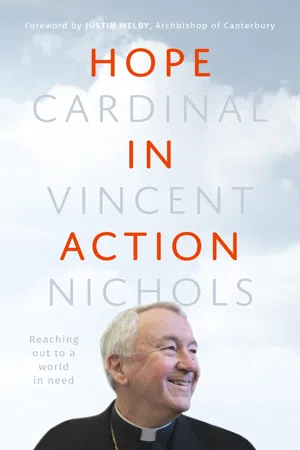

This book arises from a series of talks and lectures I gave, many of them during the Year of Mercy (8 December 2015 to 20 November 2016) declared by Pope Francis. I first of all look at what we mean by Christian hope, and what it means to be a disciple with a mission, before looking at the importance of mercy and some particular situations in which God asks us to put our Christian hope into action.

My hope is that this book, and the questions at the end of each chapter, will encourage you to be strong in your faith and in the works of mercy that spring from it.

![]()

1

Rumours of hope

There are many places in the world today where hope is in short supply. One is Erbil, among the many thousands of Christian refugees who have fled from the plain of Nineveh. Another is Gaza, where over one million Muslims are held. There can be a shortage of hope in some of our own prisons or even on some of our own streets. The concept of hope was very much on my mind after visiting Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, in 2014. This Memorial poses questions about hope in the most radical manner possible.

Yad Vashem is a powerful tribute to all who perished in the Holocaust and a damning indictment of all who perpetrated it, directly or indirectly. On my visit, only slowly did these perceptions sink deeply into my consciousness.

The journey through Yad Vashem is long and needs time. I went without a guide, with a small group of people. Fairly quickly on its zig-zag paths I lost touch with my companions. In fact I lost touch with everything: time, space, wider purpose. I quickly became absorbed in the horrendous history that was claiming my undivided attention. As I walked its paths, I had a sense of being drawn into a closed world, or rather into an understanding of how the world systematically closed its doors to the Jewish people, leaving them to their dreadful fate. Never before had I understood how abandoned they were, left without any place to go, or to call their own.

Then, too, I was drawn into the personal horrors of the victims of the Holocaust, told and retold, city by city, family by family, until reduced to yet another corpse brutally bulldozed into a pit. Never before had I felt in my deepest being the impact of the total degradation of the human person, executed on an industrial scale and here presented before my eyes.

The questions flooded in, both at the time and afterwards. How could this have happened? What are the roots of this evil? What are its consequences for generation after generation of those who perished and of those who survived? How do we live with this aspect of our past, the presence of evil in our midst?

Sin is a reality. No one remains untouched by it. But does not this Holocaust of sin and evil demand that we stop any talk of human goodness and simply stay silent in front of its abyss in which surely all hope is lost?

Yet even in Yad Vashem traces of enduring goodness are to be found. They emerge in the indomitable endurance shown by so many in the Nazi killing camps. The last words spoken by many in the gas chambers were: ‘Next year, Jerusalem.’ Traces of heroic goodness are found in the lives of those who risked all to shelter Jewish people and form with them the powerful bond, that alliance of secrecy, between the hunted and the protector. Sometimes, in Yad Vashem, I had to read the small print to find these stories. But they are there. And today this same heroism is recognized in granting the title ‘Righteous Gentile’ to those whose stories of astonishing courage emerge only now.

Perhaps there are indeed moments in which the small print of the messages of hope seemingly disappears from sight. There are many when it does not. Ours is surely the task of keeping alive these rumours of hope, however we understand them, and of knitting them together so that the far horizons of an eternal hope may never be lost to our sight.

The Holocaust may not be the most obvious starting point for thinking about hope, but it actually poses the questions very sharply: What do we mean by hope? Where, if anywhere, can we find hope? How do we understand that hope? How and where is it generated? What is its deepest nature?

What is hope?

Hope is not the same as optimism. Optimism is a disposition ‘to whistle a merry tune’, ‘to look on the bright side’, however irrational, whatever the state of things. It may or may not be realistic.

Hope is something else. The great philosopher and theologian St Thomas Aquinas treats hope in two distinct, but intimately related, parts. He first presents hope as a natural passion arising from a desire for something that is understood to be good, though it is not yet possessed; difficult, but not impossible, to attain. Hope is a movement of the will, a striving towards such a future good: an appetite which stirs up confidence and grants assurance. Thus hope abounds in young people and drunkards!

More seriously, hope moves us to become pilgrims. A hope-filled person is spurred into action when faced with something desirable, yet hard to achieve. Such hope is not the product of opinion or argument alone. We do not acquire hope just by having a point of view. There has to be something else – an impetus to act, a vision, something from within our understanding that fires our imagination, a drive consciously exercised in the effort to achieve a possible yet still a future good. Hope is a partnership between

both our understanding and our will. It moves us to get something done, something demanding, something that will make a difference. Hope gets you out of bed. Lack of hope leaves you reaching for the duvet.

Where can we find hope?

Understood this way, our world is full of signs of hope. They surround us every day. They come as daily strivings to establish, maintain, express or consolidate efforts to attain something both desired and difficult to achieve. No matter how broken our world, no matter how lacking in overall vision, there are countless fragments of hope.

What kinds of fragments do I mean? They are often the experiences of our daily lives to which we respond with warmth of heart, a quiet smile of gratitude and admiration: a neighbour’s kindness, a friend’s compassion, the utter generosity of a lover, the creativeness of a gifted person brought to a good purpose, be it the generation of wealth or a work of charity. These stories do not fill our newspapers; but they do fill our hearts and encourage us along the way.

These fragments express the strivings of hope and are themselves generative of hope in others. We can see well enough how each of them is a tiny masterpiece designed to strengthen a hope that something difficult will be achieved: the relief of suffering, the faithfulness of love, the ending of poverty, the creation of new jobs or new wealth.

More challenging is to see how these tiny fragments are in fact pieces of a mosaic, the ‘tesserae’ which when brought together can make a fine and inspiring work of art. I believe that this challenge is made all the more difficult, at least in part, by the culture of cynicism in which we live. This culture urges us to view with suspicion reports or even experiences of goodness. It tutors us to attribute to others the worst of motives, or at least to seriously entertain that perspective. World-weariness teaches us to be cautious. The misdemeanours of many institutions, including my own, emphasize that lesson. Nevertheless, we may have to learn afresh to see what is actually before us: the innate goodness of so many people.

Another factor making the formation of a coherent view of hope problematic is our culture’s embrace of relativism. By the logic of relativism nothing that others do in pursuit of their hopes or ideals is necessarily related to me since notions of what is truly good (and truly evil) are privatized. That may be good for her, but is of no interest or relevance to me. To nurture and benefit from the generative capacities of the hope we see around us, we may have to give more attention to those fragments which, if brought together, have the capacity to defeat both cynicism and relativism.

The generative capacities of hope

Let me reflect briefly on three aspects of our relationships which seem to me particularly important in thinking about how we assemble a larger picture, of which we are all a part, and thereby strengthen the generative capacities for hope. I use the word ‘generative’ because the capacity for hope is something which, given the right conditions, can grow and flourish in individuals and in society.

First, the family: our initial school of life and love. We know much about the conditions needed for the life-giving bonding of infants to their parents. Evidence for the lifelong consequences of early childhood trauma and dislocation is powerful. The experience of healthy childhood development, including experiencing failure and forgiveness, and the learning of gratitude, deeply influences our adult selves and our capacity for hope and trust in others. It follows that a society that cares about the quality of hope for the future will care hugely, in an objective and systematic way, about factors which help or hinder the family.

Second, beyond but founded on the family, is what Rabbi Jonathan Sachs speaks of as the social sphere. He describes this sphere as ‘covenantal’, always based on a kind of covenant we make with others as we engage together in work or projects, outside of the political or economic spheres. This covenantal activity generates trust between us. Effective political life and creative economic activity depend on trust. But they do not so easily generate trust. In fact they tend to consume trust. So the social sphere is crucial: it is the place where our identity as social beings, whose fulfilment is bound up with that of others, finds expression. But more importantly in this place, hope is something carried by the community and not just by the individual. For a common project or goal that is difficult yet possible to attain, one week your commitment and belief stirs me from my apathy and desponde...