- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

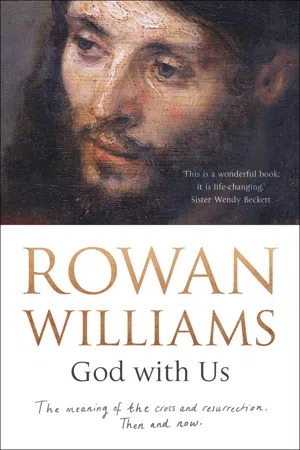

From the pen of one of our greatest living theologians, here is a fresh and compelling introduction to the foundation story of the Christian faith.

Full of illuminating theological insight and spiritual encouragement. Designed for use by individuals or groups, with questions for reflection or discussion at the end of each chapter. An ideal gift for anyone near the start of their spiritual journey or wanting to deepen their appreciation of the heart of the gospel.

Part One: The meaning of the Cross

1. The sign

2. The sacrifice

3. The victory

Part Two: The meaning of the Resurrection

4. Christ's resurrection then

5. Christ's resurrection now

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access God With Us by Rowan Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

THE MEANING OF THE CROSS

1

The sign

For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you should follow in his steps. ‘He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth.’ When he was abused, he did not return abuse; when he suffered, he did not threaten; but he entrusted himself to the one who judges justly. He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that, free from sins, we might live for righteousness; by his wounds you have been healed.

(Peter 2.21–24, NRSV)

When we go into a Christian place of worship, we expect to see a cross. And when crosses are removed from public places, such as crematoria or hospital chapels, we quite reasonably get rather indignant about it. But in the world in which Christianity began, a place of worship was the last place you would expect to see a cross. We can only begin to get some sense of what it might have felt like to encounter the symbol of a cross in the first couple of Christian centuries if we imagine coming into a church and being faced with a large picture of an electric chair, or perhaps a guillotine. The cross was a sign of suffering, humiliation, disgrace. It was a sign of an all-powerful empire that held life very cheap indeed: a forceful and immediate reminder to everybody that their lives were in the hands of the state. You might well be used to seeing crosses on the outskirts of towns or by the side of the road, but most definitely not in any place of worship.

When Jesus was a small boy there was a revolt in Galilee that was brutally suppressed by the Romans. We’re told that there were thousands of crosses by the roads of Galilee. When in the Gospels Jesus speaks of picking up your cross and following him, he is not using a religious metaphor for things becoming a bit difficult.

So a group of people who proclaimed that the sign of their allegiance was a cross had a lot of explaining to do; and so we will be looking at some of the ways in which the first Christians tried to explain themselves. Because once we get past the surface level of being used today to seeing crosses around as a religious symbol, once we let ourselves recognize what it is that we are looking at, we are bound to be faced with some of the same questions. What is this about? How does it work? Why do we have an instrument of torture at the centre of our imagination?

The early Christians must have felt that they had no option but to talk about the cross. They knew that because of the death of Jesus on the cross their universe had changed. They no longer lived in the same world. They expressed this with enormous force, talking about a new creation, about liberation from slavery. They talked about the transformation of their whole lives and they pinned it down to the events that we remember each Good Friday. They couldn’t get away from the cross – or so at least the New Testament seems to imply. There are in fact some New Testament scholars who try to argue that reflection on the cross of Jesus came in a little bit later. First came Jesus the charismatic teacher, the wandering prophet; first came an interest in his words rather than his deeds or his sufferings. And yet, when you read the earliest texts of Christian Scripture, not only the Gospels, it’s difficult to excavate any stratum of thinking that is, as you might say, ‘pre-cross’. Pretty well everything we read in the New Testament is shadowed by the cross. It is, first and foremost, the sign of how much has changed and how it has changed.

Even non-Christians in the world around recognized the central importance of the cross to Jesus’ early followers. The earliest picture we have of the crucifixion is scratched on a wall in Rome; it may be as old as the second century. It is a rather shocking image: a man with a donkey’s head strapped and nailed to a cross, and next to the cross a very badly drawn little figure wearing the short tunic of a slave, and scribbled above it, ‘Alexamenos worshipping his god’. Presumably one of Alexamenos’s fellow slaves had scrawled this little cartoon on the wall to make fun of him. But he knew, as Alexamenos knew, that Alexamenos’ god was a crucified God.

The first Christians had some explaining to do; and so do we. In one of the great Christian poems of the twentieth century (the second of the Four Quartets), T. S. Eliot writes, ‘Again, in spite of that, we call this Friday good.’ That’s the agenda for our reflections in this chapter: why is this instrument of suffering and death a sign of what is good?

The early Christians were at a huge disadvantage. They claimed that the world had changed because somebody had been executed by a death normally reserved for slaves and rebels. They were saying that their new life depended on somebody who had been so much at odds with the Roman world that the full force of the empire had crushed him. That might not in itself have been fatal if it had been possible to say that he died because he was defending his nation and his faith. In the couple of centuries just before the birth of Jesus, the Jewish people had begun to develop theories about martyrdom. They had come to believe that when somebody died for the law and for the nation, that person’s death was pleasing to God: there’s a phrase from a text of that time, affirming that ‘God considers the soul of a man to be a worthy sacrifice.’ But Jesus did not die defending the nation or the law against foreign oppression. He died because those who ruled his nation had collaborated with the oppressor. The early Christians were thus caught in a sort of pincer movement: here was somebody condemned by the state and rejected by the religious authorities of his own people. So, imagine you’re an early Christian and this is your sign. What is it a sign of?

Sign of God’s love and freedom

Several times in the New Testament we encounter a phrase like ‘God demonstrates’ or ‘proves’ his love for the world by or through the cross. It’s there, for example, in Romans 5.8: ‘Christ died for us . . . and that is God’s own proof of his love towards us.’ We find similar language in 1 Timothy 2 and several times in the first letter of John. God has ‘proved’ his love for us through Jesus, and particularly through the death of Jesus. The Gospel of John goes even further, speaking of the death of Jesus as his ‘glorification’: when Jesus dies God’s glory becomes fully manifest. So the execution of Jesus is a proof that God loves us, and so is also a demonstration of the kind of God that we are talking about. In John 12 Jesus says: ‘When I am lifted up, I will draw everyone to me’ – and the context makes it clear that his hearers are puzzled and shocked by the allusion to crucifixion. This is how the early Christians begin to push back at the expectations, you might almost say the clichés, of the world around. Yes, the cross is our sign and it is a sign of the kind of God we believe in.

How then does the execution of Jesus show the love of God? How does it become that sort of sign? We have a hint in Luke 23.34 and in the first letter of Peter 2.23. In Luke, as Jesus is crucified he says, ‘Father, forgive.’ And in Peter’s letter we are reminded that when Jesus is abused he doesn’t retaliate: ‘When they hurled their insults at him, he did not retaliate.’ Here is a divine love that cannot be defeated by violence: we do our worst, and we still fail to put God off. We reject, exclude and murder the one who bears the love of God in his words and work, and that love continues to do exactly what it always did. The Jesus who is dying on the cross is completely consistent with the Jesus we have followed through his ministry, and this consistency shows that we can’t deflect the love that comes through in life and death. So when Pilate and the High Priest – acting on behalf of all of us, it seems – push God in Jesus to the edge, God in Jesus gently but firmly pushes back, doing exactly what he always did: loving, forgiving, healing.

So the cross is a sign of the transcendent freedom of the love of God. This is a God whose actions, and whose reactions to us, cannot be dictated by what we do. You can’t trap, trick or force God into behaving against his character. You can do what you like: but God is God. And if he wants to love and forgive then he’s going to love and forgive whether you like it or not, because he is free. Our lives, in contrast, are regularly dominated by a kind of emotional economics: ‘I give you that; you give me this.’ ‘I give you friendship; you give me friendship.’ ‘You treat me badly, and I’ll treat you badly.’ We’re caught up in cycles of tit-for-tat behaviour. But God is not caught up in any cycle: God is free to be who he decides to be, and we can’t do anything about it.

The cross is a sign of the transcendent freedom of the love of God

And that’s the good news: the good news of our powerlessness to change God’s mind. Which is just as well, because God’s mind is focused upon us for mercy and for life. God will always survive our sin, our failure. God is never exhausted by what we do. God is always there, capable of remaking the relationships we break again and again. That’s the sign of the cross, the sign of freedom.

It’s out of that aspect of the New Testament – one strand among several – that the tradition arises in Christian history that has sometimes been called ‘exemplarism’: the cross of Christ is an example. ‘Christ . . . suffered for you, leaving you an example,’ says 1 Peter 2.21. Jesus was free from the vicious circle of retaliation, and so can we be and so should we be. Christ did not retaliate, return abuse for abuse; so neither should we. In the Acts of the Apostles we see that the free forgiveness of Jesus on the cross is already shaping the response of the disciples, because when Stephen – the first martyr – faces his execution, he says something very similar to what Jesus says. What Jesus said to the Father, Stephen says to Jesus: ‘Do not hold this sin against them’ (Acts 7.60). Already, it seems, the way in which Jesus died on the cross has become a model that Christian believers must follow. And so, if we imitate the non-violent, non-retaliatory response of Jesus, we ourselves become a sign of the same divine love. We in our lives, in our willingness to be reconciled, show the world what kind of God we believe in: a God who is free from the vicious circle of violence and retaliation.

But it’s not only that. The cross is an example to us but also an example for us. It is, in the old sense of example, a ‘sample’ of the love of God. This is what the love of God is like: it is free and therefore it is both all-powerful and completely vulnerable. All-powerful because it is always free to overcome, but vulnerable because it has no way of guaranteeing worldly success. The love of God belongs to a different order, not the order of power, manipulation and getting on top, which is the kind of power that preoccupies us. This takes us a bit beyond what the New Testament says in so many words, but only a bit. It’s a very natural way for the idea to develop, and it’s been very powerful in much Christian thinking. It allows us to say that the love of God is the kind of love that identifies with the powerless; the kind of love that appeals to nothing but its own integrity, that doesn’t seek to force or batter its way through. It lives, it survives, it ‘wins’ simply by being itself. On the cross, God’s love just is what it is and it’s valid and world-changing and earth-shattering, even though at that moment what it means in the world’s terms is failure, terror and death.

This is what the love of God is like: it is free and therefore it is both all-powerful and completely vulnerable

This has always been for Christians a hugely powerful idea: the defencelessness of the love of God, a love which has nothing but itself to rely on and yet somehow is all powerful. The weakness of God, said Paul, is stronger than human strength (1 Corinthians 1.25). And such a love – so many Christians have said – draws us towards Jesus. It has a magnetic force because it is a love that can’t threaten us. How could we say no?

One of the people who most fully developed and reflected on this aspect of the cross was the twelfth-century philosopher and theologian Peter Abelard. He taught for many years in the schools of Paris, met with terrible personal tragedy and disaster, and ended his life as a monk. And it was he who first dwelt at length on the idea that the death of Jesus on the cross exemplifies a love that, when we have seen how it works, we simply can’t refuse. One of the great novels of the twentieth century dealing with the Christian faith is Helen Waddell’s Peter Abelard, a book in which Helen Waddell, a formidable scholar of the Middle Ages, seems to get right into the mind and the heart of Peter Abelard and of his lover and wife Eloise, and of the people around them – so much so that you really feel you are in Paris in the twelfth century and, yes, this must have been what they said to each other.

I’d like to dwell on two moments from that book. One is when Peter, in disgrace and deep despair, is trying to rebuild his life out in the country, having built a little hermitage. One of his former students is living alongside him, helping him with practical work and joining him at the altar. One day they’re coming back from fishing and they hear a terrible cry, like a child’s cry, coming from the woods behind them. They rush in the direction of the cry and find that it’s not a child, it’s a rabbit caught in a trap, squealing its life away in terrible anguish. They prise open the trap, the rabbit nestles its head for a moment in the crook of Peter’s arm, and dies. And Peter feels for that moment overwhelmed by the sheer horror of the suffering that runs right through the world: his own suffering, the suffering he’s inflicted on his wife, the suffering of this innocent animal. And to his amazement it’s the student, Thibault, who has something to say to him.

‘I think,’ says Thibault nervously, ‘God is in it too.’

Abelard looked up sharply.

‘In it? Do you mean that it makes Him suffer, the way it does us?’

Again Thibault nodded.

‘Then why doesn’t He stop it?’

Thibault points to a tree near them:

That dark ring ...

Table of contents

- CoverImage

- Praise

- About the author

- Title Page

- Imprint

- Contents

- Part 1: The Meaning of the Cross

- Part 2: The Meaning of the Resurrection

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements