- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

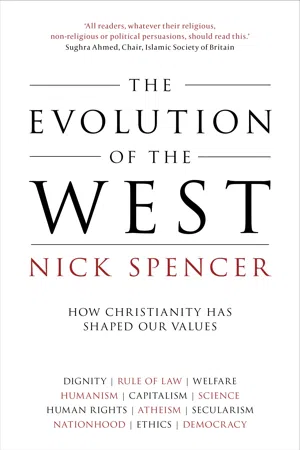

What has Christianity ever done for us?

A lot more than you might think, as Nick Spencer reveals in this fresh exploration of our cultural origins.

Looking at the big ideas that characterize the West, such as human dignity, the rule of law, human rights, science – and even, paradoxically, atheism and secularism – he traces the varied ways in which many of our present values grew up and flourished in distinctively Christian soil.

Always alert to the tensions and the mess of history, and careful not to overstate the Christian role in shaping our present values, Spencer shows how a better awareness of what we owe to Christianity can help us as we face new cultural challenges.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Evolution of the West by Nick Spencer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why the West is different

1

History writes historians just as much as historians write history. The presuppositions of an age, the shadows it lives under, the light it thinks it grows towards: all inform how it narrates its past. Hume’s histories of England and Gibbon’s of Rome could only have been written in the eighteenth century. William Stubbs, Lord Acton and Jacob Burckhardt all bear the marks of progressive liberty and autonomy that characterize the later nineteenth century. History books may not exemplify their age in the way that styles of architecture are supposed to, but they illustrate them.

So it is today. The secularization thesis ground to a halt at some point in the last quarter of the twentieth century, as the rest of the world veered off Europe’s tracks and modernized without losing their religion, and the more muscularly religious emerged from the darkness to batter down the secular defences that the West had erected around itself.

In reaction to this, a number of historians of recent years have been keen to bang the drum for the secular Enlightenment, defining, defending and celebrating it as the font of all our social and political liberties. These have ranged from the crudest New Atheist caricatures, through Anthony Pagden’s The Enlightenment: And Why it Still Matters, all the way to Jonathan Israel’s awe-inspiring 2,500-page trilogy on the Enlightenment. One should not, of course, expect too much from New Atheist polemics, intended as they are to dish out the most savage punishment beatings to the flimsiest of straw men, but when someone as erudite as Israel writes …

Nothing could be more fundamentally mistaken, as well as politically injudicious, than for the European Union to endorse the deeply mistaken notion that ‘European values’ … are at least religiously specific and should be recognised as essentially ‘Christian’ values. That the religion of the papacy, Inquisition, and Puritanism should be labelled the quintessence of ‘Europeanness’ would rightly be considered a wholly unacceptable affront by a great majority of thoroughly ‘European’ Europeans.

… we clearly have a problem and can be sure that the atmosphere of the age is colouring the pages of our history.

In such a context it takes an impressive and courageous historian to say that in actual fact the Enlightenment is not the source of our political virtues, and that these are better found in distinctly Christian ideas and their institutional setting (whisper it: the Church). Larry Siedentop is that man.

2

Siedentop is a septuagenarian academic who studied under Isaiah Berlin and whose evident approval of secular liberal values does not mean he is blind to their origins or complacent about their future.

His book Inventing the Individual traces the history of certain ideas: that each person exists with worth apart from their social position; that everyone should enjoy equal status under the law; that none should be compelled in their religious beliefs; that each has a conscience that should be respected. These are ideas that many of us deem either obvious or ‘natural’ for humans to hold, or that we locate firmly in the Enlightenment. Such ideas are, in fact, very far from ‘natural’, however, and have their roots many centuries before Voltaire ever put quill to paper.

Inventing the Individual begins in the world of antiquity. This is sometimes taken, in more fanciful quarters, as the nursery of freedom. Yes, slavery might have been institutionalized but polytheism was tolerant, much of it was devoid of serious religion, the free were all equal and many people even had the vote.

In reality, the ancient world was anything but secular, tolerant, free or equal. Religion was omnipresent, and the family was everything: the primary social institution and source of identity, the basic unit of social reality, a veritable (and repressive) church in itself. The paterfamilias was effectively a magistrate and high priest with almost unlimited powers. Social roles were fixed and hierarchy and inequality were believed to be built into the universe itself. There was simply no conception of common humanity, and widespread charity (i.e. outside immediate family or clan bonds) ‘was not deemed a virtue, and would probably have been unintelligible’.

This changed with the emergence of city states, which widened the bonds that had been the property of the family, although not by much. Families remained exclusive and powerful, their power now pooled in cities. Citizens belonged to the city and there was little space for individual conscience. The individual simply did not exist outside family, city or cult.

Cities were inherently religious institutions: quasi-churches, as families had been, patriotism and piety being essentially the same thing. War was tied in with the purpose and worth of the civic realm, and there was no clear distinction between military and economic activity. The pagan gods were no less jealous of their cities than Yahweh was of his people.

As the world changed from city states to empire, these localized social ties loosened but, again, progress was slow. Primogeniture weakened, younger sons became full citizens, the absolute power of the paterfamilias weakened, their sacred status eroded. Such progress was ambiguous, however: local city loyalties (and deities) faded only to be replaced with the God of Rome, whom you crossed at your peril. It was also strictly limited. Women and slaves were still non-persons, confined to the dishonourable and inferior worlds of the home and manual labour. The second-century jurist Gaius could rely on three tests to establish a person’s status: Were they free or unfree? A citizen or foreign born? A paterfamilias or in the power of an ancestor? This was enough to tell whether they were worth anything. Roman law, which would play such a significant role in the wake of the Western empire, was limited to relations ‘between men who shared in the worship of the city, sacrificing at the same altars. They alone were citizens.’

There were a few small groups who challenged this social structure, such as the Sophists, peripatetic and paid professional teachers, often of modest backgrounds, who questioned the order of city, empire and universe. But they were few and limited in their challenge. The powerful idea, favoured by some Enlightenment historians and their eager acolytes today, that we can draw any kind of line, let alone a neat and straight one, from the allegedly tolerant and equal liberties of the ancient world to those of today is a myth almost entirely without foundation.

3

It was into this world that Christianity erupted in what Siedentop calls a ‘moral revolution’. Siedentop’s description of this eruption is slightly eccentric. He rightly sees the Jewish concept of law – as a statement of God’s will that transcends human rational considerations and is thus free from the hierarchical connotations of Roman law – as the foundation for the Christian moral revolution. However, because he deals only briefly with Jewish thought and speaks of inter-testamental Judaism as a single thing, he doesn’t recognize that, by the time of Jesus, the ‘wisdom’ or Sophia of God is not only spoken of as radiating or emanating from him, but also discernible within creation. In effect, the conception and re-description of divine activity and law in terms that would be comprehensible to the Hellenic mind, had begun before St Paul.

Similarly, Siedentop locates the Christian moral revolution in Paul rather than Christ (whom he calls ‘the Christ’ throughout) on the somewhat spurious grounds that we can say very little confidently about Jesus’ life and teachings. This would be news to many New Testament scholars and, of course, to Paul himself, who had no doubts where his teaching was grounded. Siedentop does not imagine that Paul is an inventor, in the way that some like to claim that Paul ‘invented’ Christianity, but he fails to grant Paul’s thought its full intellectual heritage or context. However brilliant and influential he was, Paul was not the sum of early Christianity.

Such quibbles aside, Siedentop is forcefully clear on what Paul’s message did revolutionize: ‘the Christ reveals a God who is potentially present in every believer.’ Through an act of faith in the Christ, human agency, which is no longer simply a plaything of stars, gods or fate, can become a medium for God’s love. Such an understanding of reality deprived rationality of its aristocratic connotations. Thinking was no longer the privilege of the social elite and became associated not with status but with humility, itself a virtue entirely alien in the ancient world.

Christianity put forward a new idea of a voluntary basis for human association in which people joined together through will and love rather than blood or shared material objectives. In doing so, it helped redefine identity, which was no longer exhausted by social roles, these becoming secondary to the primary relationship with God. For the first time, humans (all humans) had a ‘pre-social’ identity, being someone before they had some role. This provided ‘an ontological foundation for “the individual”’ through the promise that humans have access to the deepest reality as individuals rather than merely as members of a group. Martyrs in particular became examples of this inner conviction, standing against social and political forces and norms to an extreme degree; examples, if you will, of conscience. ‘The unintended consequence of the persecution of Christians was to render the idea of the individual, or moral equality, more intelligible.’

This was reinforced by the near-universally recognized fact – even among hostile pagans – that churches ‘amounted to mini-welfare states’, tending to treat ‘our’ poor as well as its own, as the emperor Julian the Apostate put it. The Church was inclusive and universal in a way that nothing else was in the ancient world, its sacraments emphasizing the individuality and equality of all.

Even those things, like sexual renunciation, which we modern liberals like to sneer at and are now seen as part of Christianity’s repressive side were, in this context, actually liberating. In a society where women were defined by their reproductive role, sexual renunciation was a manifest act of individual will and constituted a powerful statement of independent dignity. Indeed, it was a subtle assertion of control over man – that a woman’s body was her own to choose what she did with it rather than simply being a receptacle for a man’s desire to breed – an assertion that could only be legitimized by a higher authority. A similar re-balancing of gender power was to be seen in the Church’s relentless emphasis that the obligations within marriage were mutual and that male adultery was as worthy of condemnation as female. No one, and certainly not Siedentop, is under any illusion about how church leaders could treat women, but in the realm of fundamental ideas there is a different story to be told.

4

What actual impact did this moral reformation have? The answer is a slow one. Siedentop traces the line of Christian ideas through Europe’s murkiest centuries.

After the final collapse of the empire in the West in 476, ancient hierarchies were in a shambles. The Church was the last institution left standing and bishops frequently became leading civic figures. They found themselves negotiating with Germanic invaders who had the monopoly of physical force and whose culture entailed the supreme power of the paterfamilias, subordination of women and inflexible rules concerning inheritance, all of which were antithetical to, or at least in some tension with, core Christian ideas.

The clergy thus often became ‘diplomats and administrators’. Their only viable response to the violence that confronted the broken empire was to wield a moral axe – or, perhaps, moral stick and carrot – with the invaders. On the one hand, they declared that God would judge each and every person for their actions; on the other, they sought to ‘introduce the norm of “charity”’ into public life. In this way ‘concern with the fate of the individual soul was nibbling away at a corporate, hierarchical image’ – doing unto the Germanic invaders what it had done to the Roman empire they now overran.

Charity was inextricably linked with education and one of the most refreshing critiques in Siedentop’s book is of the changing educational landscape of the mid-first millennium. The traditional story here is that ancient learning was free and tolerant, reasonably sophisticated and rational, only to be (brutally) closed down by ignorant monks who, if they thought at all, were obsessed by incomprehensible and essentially meaningless theological details.

While you can certainly defend this line, Siedentop argues persuasively that the educational system of late antiquity was nothing like as polished as we imagine it. The dependence of professors on imperial favour and the strict regulation of students had resulted in forms of intellectual servility and a severely devalued syllabus. Students came from a privileged class and learning was primarily a matter for display, ‘ornament rather than substance’. If you want a more modern comparison, think an Oxford education c.1750.

By contrast, Siedentop contends, Christian learning was shaped by the fact that bishops were immersed in the world. They couldn’t do rhetoric for rhetoric’s sake. Moreover, they were discussing live issues, questions that were not yet settled, unlike most subjects within the lecture halls of late antiquity, and were therefore engaged in thinking rather than just learning. In this way, ‘the church gave ancient philosophy an “afterlife”’, as well, of course, as preserving most of ancient texts, Christian and pagan alike, that we have today.

The centre for this preservation of thought was the monasteries but monasteries did more for the idea of the individual than in their educational role alone. Although deplored by many urban clergy at first for their ignorance and cussedness, monks epitomized Christianity’s potential for inwardness. They existed alone, defined not by any social role but by God alone. ‘The monks could be portrayed as a new type of athlete, an athlete who sought not physical perfection or competitive glory but conquest of the will.’

When, from the fourth century, they began to live corporately, their ‘sociability [preserved] the role of individual conscience’. The new form of social organization was self-regulatory. Monasteries created ‘an unprecedented version of authority [where] to be in authority was to be humble’. They helped rehabilitate work as a good in itself.

At the end of antiquity the image [monasticism] offered of a social order founded on equality, limiting the role of force and honouring work, while devoting itself to prayer and acts of charity, gave it a powerful hold of minds.

Again, as with the treatment of women, this is an idealized picture and, again, Siedentop is alert to the monasteries’ very many ‘failings and compromises’. But while we dwell in the realm of ideas, it remains an important corrective to the well-worn narratives of monastic darkness, bigotry and ignorance.

5

Monasticism – at its best – may have preserved and nurtured Christianity’s integral values through Europe’s most turbulent centuries, but that does not mean the rest of the West was utterly devoid of them. This is the fact that will, perhaps, most surprise the casual reader of Inventing the Individual, schooled, as most of us are, in the belief that these were unremittingly barbaric centuries within a generally barbaric millennium.

As an example, Siedentop quotes the remarkable legal formula of King Chilperic, from the mid-sixth century, concerning the status of women in his kingdom.

A long-standing and wicked custom of our people denies sisters a share with their brothers in their father’s land; but I consider this wrong, since my children came equally from God … Therefore, my dearest daughter, I hereby make you an equal and legitimate heir with your brothers, my sons.

These are not the words or laws we expect to have emerged from the gloomiest corner of the ‘Dark Ages’.

The surprises do not end with gender. The plight of the poor was repeatedly highlighted in such a way as emphasized the scandal of poverty among those for whom Christ died. ‘Their sweat and toil made you rich. The rich get their riches because of the poor’, thundered Bishop Theodulf of Orleans, like a mitred Marx. ‘But nature submits you to the same laws. In birth and deat...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Why the West is different

- 2 A Christian nation

- 3 Trouble with the law: Magna Carta and the limits of the law

- 4 Christianity and democracy: friend and foe

- 5 Saving humanism from the humanists

- 6 Christianity and atheism: a family affair

- 7 The accidental midwife: the emergence of a scientific culture

- 8 ‘No doubts as to how one ought to act’: Darwin’s doubts and his faith

- 9 The religion of Christianity and the religion of human rights

- 10 The secular self

- 11 ‘Always with you’: Capital, inequality and the ‘absence of war’

- 12 Christianity and the welfare state

- Books consulted

- Search terms