- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

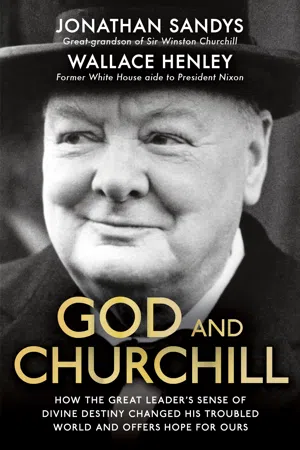

God and Churchill HB

About this book

When Winston Churchill was a boy of sixteen, he already had a vision for his purpose in life. "This country will be subjected somehow to a tremendous invasion ...I shall be in command of the defences of London ...it will fall to me to save the Capital, to save the Empire." It was a most unlikely prediction. Perceived as a failure for much of his life, Churchill was the last person anyone would have expected to rise to national prominence as prime minister and influence the fate of the world during World War II. But Churchill persevered, on a mission to achieve his purpose. God and Churchill tells the remarkable story of how one man, armed with belief in his divine destiny, embarked on a course to save Christian civilization when Adolf Hitler and the forces of evil stood opposed. It traces the personal, political, and spiritual path of one of history's greatest leaders and offers hope for our own violent and troubled times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access God and Churchill HB by Jonathan Sandys and Wallace Henley,Jonathan Sandys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE REMARKABLE PREPARATION

1

A Vision of Destiny

This country will be subjected somehow, to a tremendous invasion, by what means I do not know, but I tell you I shall be in command of the defences of London, and I shall save London and England from disaster.

WINSTON CHURCHILL, AGE 16

ON A SUMMER SUNDAY EVENING IN 1891, with the echoes of chapel evensong still resonating in their minds, sixteen-year-old Winston Churchill and his close friend and fellow Harrow student Murland de Grasse Evans sat talking in what Evans would remember years later as ‘one of those dreadful basement rooms in the Headmaster’s House’.1

The conversation focused on destiny – more specifically, their own. Churchill thought that Evans might go into the diplomatic service, or perhaps follow his father’s footsteps into finance.

Then Evans asked Churchill, ‘Will you go into the army?’

‘I don’t know’, young Winston replied. ‘It is probable; but I shall have great adventures soon after I leave here.’

‘Are you going into politics? Following your father?’

‘I don’t know, but it is more than likely because, you see, I am not afraid to speak in public.’

Evans was quizzical as he gazed back at his friend. ‘You do not seem at all clear about your intentions or desires.’

‘That may be,’ Winston shot back, ‘but I have a wonderful idea of where I shall be eventually. I have dreams about it.’

‘Where is that?’

‘Well, I can see vast changes coming over a now peaceful world; great upheavals, terrible struggles; wars such as one cannot imagine; and I tell you London will be in danger – London will be attacked and I shall be very prominent in the defence of London,’ Winston said.

‘How can you talk like that?’ Evans asked. ‘We are forever safe from invasion, since the days of Napoleon.’

‘I see further ahead than you do,’ Winston replied. ‘I see into the future.’

Murland Evans was so ‘stunned’ by the conversation that he ‘recorded it with utmost clarity’, in a letter he sent to Churchill’s son, Randolph, who in the 1950s was given the responsibility of writing his father’s biography.2

Churchill continued, undaunted, as he would many times throughout his career. ‘This country will be subjected somehow, to a tremendous invasion, by what means I do not know, but I tell you I shall be in command of the defences of London, and I shall save London and England from disaster.’

Evans remembered Churchill as ‘warming to his subject’ as he spoke.

‘Will you be a general, then, in command of the troops?’ Evans asked.

‘I don’t know,’ Britain’s future leader replied. ‘Dreams of the future are blurred, but the main objective is clear… . I repeat – London will be in danger and in the high position I shall occupy, it will fall to me to save the Capital and save the Empire.’3

NEED FOR AFFIRMATION

Were it not for events almost fifty years later, young Winston’s prediction might be dismissed as the desperate effort of a lonely adolescent with a need for affirmation to assert his significance. That need would have been understandable, given the relationship between Churchill and his physically and emotionally removed parents. Of his mother, Churchill wrote later in life, ‘I loved her dearly – but at a distance.’4 And once, after an extended conversation with his own son, Churchill remarked, ‘We have this evening had a longer period of continuous conversation than the total which I ever had with my father in the whole course of his life.’5

Today, social conventions are often determined by their political correctness. In Churchill’s day, especially for people of his class, it was ‘Victorian correctness’ that set the standard. VC demanded a certain aloofness of parents towards their children. In some households, parents met with their offspring by appointment only (determined by the parent) and in the presence of a servant. If the child became too troublesome, obnoxious or impolite, the help could quickly take charge.

As a boy, Winston romanticized his parents at times. He saw his father as a champion of ‘Tory democracy’. History focuses on Lord Randolph’s personal morality, but Winston saw his father as a good and loyal politician who stood on principle. He noted his father’s courageous stands as Chancellor of the Exchequer – and how, when Lord Randolph’s voice was ignored, he offered his resignation. Churchill admired the fact that Lord Randolph was sometimes unpopular and that he placed the nation’s needs above those of his own Conservative Party when he perceived a conflict. Winston believed his father to be a ‘people’s politician’, not a party hack. He concluded that Lord Randolph sincerely desired to serve the people he represented and was not in politics for himself, for power or for accolades.

Churchill’s mother, Jennie, was an active socialite, if not a libertine, with many (some would say scandalous) involvements; but her relationship with her young son was not especially close. Still, Churchill remembered her as ‘a fairy princess: a radiant being possessed of limitless riches and power’.6

‘Emotionally abandoned by both [parents], young Winston blamed himself,’ writes the historian William Manchester. ‘Needing outlets for his own welling adoration, he created images of them as he wished they were, and the less he saw of them, the easier that transformation became.’7 Aristocratic families sent their boys to private boarding schools – for Winston, it was Harrow – and at a distance, Winston’s fantasized image of his parents was quite easy to maintain because he did not see them often or receive communications from them.

At one point, he tried to tell his mother how lonely he was: ‘It is very unkind of you not to write to me before this, I have only had one letter from you this term.’8 In 1884, four years before he entered Harrow, nine-year-old Winston became sick. His doctor, who had a medical office in Brighton, felt it would be good for the boy’s health if he lived for a while by the sea. Thus, Churchill started that autumn as a student at a school there. But the new location made no difference in his parents’ attentiveness. In fact, when he read in the Brighton newspaper that Lord Randolph had recently been in town to make a speech, Winston wrote him a note: ‘I cannot think why you did not come to see me, while you were in Brighton. I was very disappointed, but I suppose you were too busy to come.’9

Then there were the suffocating strictures of the upper-crust educational institutions. As William Manchester observes, ‘Youth was an ordeal for most boys of [Churchill’s] class. Life in England’s so-called public schools – private boarding schools reserved for sons of the elite – was an excruciating rite of passage.’10 Added to that misery was the continuing disregard by his parents. ‘It is not very kind darling Mummy to forget all about me, not answer my epistles,’ he wrote in one letter to his mother.11 On another occasion, Winston asked his father to come to Harrow for Speech Day and told him, ‘You have never been to see me & so everything will be new to you.’12

As difficult as his parents’ seeming disinterest must have been for Churchill, it may have been a blessing in disguise. By default, his nanny, Elizabeth Everest, played a much bigger role in forming his vital foundational beliefs, and her perspective was decidedly Christian.

WOOMANY

Winston Churchill’s school experience was pathetic by any measure, but right from the start, even as a seven-year-old, he demonstrated the tenacity and determination that would come to characterize his life. Subjected to institutional acts of brutality that might have destroyed another boy’s morale, Churchill remained resolute. Once, after a particularly severe caning at St George’s School in Ascot, he got his revenge by defiantly stamping on the headmaster’s prized straw hat.

At the bottom of his class – and also sorted towards the end of the list at roll call because of his name, Spencer-Churchill – Winston wrote pleadingly to his father to allow him to dispense with the Spencer and simply go by Churchill. Lord Randolph ignored the letter, just as he had failed to respond to the hundreds of earlier epistles in which the homesick young Winston begged them to visit for a weekend, Sports Day, Prize Giving or any occasion.

During those dark eleven years of Churchill’s primary schooling, he had only one visitor: his nanny, Mrs Elizabeth Everest, whom he affectionately called Woomany. She was the one person to whom he ‘poured out [his] many troubles’.13 Churchill and Mrs Everest remained friends and confidants until her death in 1895, five months after Lord Randolph’s and three months after his grandmother’s, Clarissa Jerome. ‘I shall never know such a friend again,’ Churchill wrote of Everest in a letter to his mother.14

During Churchill’s younger years, Mrs Everest loved him dearly and protected him as best she could. Years later, when he wrote his only novel, Savrola, Churchill no doubt had Mrs Everest in mind when he described the housekeeper character:

It is a strange thing, the love of these women. Perhaps it is the only disinterested affection in the world. The mother loves her child; that is maternal nature. The youth loves his sweetheart; that too may be explained… . In all there are reasons; but the love of a foster-mother for her charge appears absolutely irrational. It is one of the few proofs, not to be explained even by the association of ideas, that the nature of mankind is superior to mere utilitarianism, and that his destinies are high.15

Stephen Mansfield provides further insight into Elizabeth Everest’s influence on Churchill. She was a ‘low church adherent’, he notes, who wanted no part of the ‘popish trappings’ in the Anglican Church. ‘But she was also a passionate woman of prayer, and she taught young Winston well. She helped him memorize his first Scriptures, knelt with him daily as he recited his prayers, and explained the world to him in simple but distinctly Christian terms.’16 Her role in the formation of Churchill’s world view was still evident later in his life when he often paraphrased or quoted Bible passages in his speeches. Even in seasons of doubt, he instinctively saw through eyes formed with a biblical outlook. This is why he could inspire hope, call for strength and faith and, most importantly, grasp the true meaning of Nazism and its threat to civilization.

Throughout his life, Winston Churchill was a man of principle, even though his understanding and application of those principles were sometimes skewed – as they are in all of us. The academics under whom Britain’s future wartime leader studied would have been well acquainted with the writings of Jeremy Bentham, the prominent late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century British philosopher who promoted the theory of utilitarianism and the idea that outcomes determined the ethical rightness of actions and philosophies. Churchill was a practical man, but he was not a mere utilitarian. Instead, he combined a mighty visionary perspective, strategic wisdom and tactical knowledge in ways rarely found in one person.

Early in his political career, Churchill angered his friends and won only meagre approval from his former opponents when he changed political parties over policy principles. After the seeming collapse of his leadership reputation during the First World War, Churchill only dug the ditch deeper with his attempts to warn about the intentions of Adolf Hitler during the build-up to the Second World War. To regain his credibility and stature, it would have been much easier to give way to raw pragmatism and mute his message. The more comfortable course would have been to yield to Britain’s war-weariness and allow Hitler free rein in Western Europe. After all, key players in the British aristocracy didn’t think all that bad...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Praise for this book

- Title page

- Imprint

- Dedication

- Table of contents

- Epigraph

- Foreword by James A. Baker III

- Preface by Cal Thomas

- Introduction

- Part I: The Remarkable Preparation

- Part II: Destiny

- Part III: Saving ‘Christian Civilization’

- Part IV: Hope for Our Time

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Search items

- About the Authors

- Plates